The Innovation Platform spoke to Dr Sarah Gallagher, Director of Western Space, to find out how the institute’s interdisciplinary approach to space science is addressing the key challenges facing today’s world.

Located in Ontario, Canada, the Institute for Earth & Space Exploration (Western Space) at Western University is dedicated to tackling some of the most pressing challenges in space science and exploration.

With an interdisciplinary approach to activities and innovation, Western Space provides leadership and programmes to advance research in the space domain at the university and beyond. To learn more about the institute’s recent work across a variety of disciplines, Editor Georgie Purcell spoke to Western Space’s Director, Dr Sarah Gallagher.

Can you briefly tell us more about Western Space and the key objectives of your activities?

Western Space is one of four interdisciplinary research institutes at Canada’s Western University. We have a long legacy, having been first known as the Centre for Planetary and Space Exploration before transitioning to an institute in 2019. The fact that space has been chosen as the focus for four institutes indicates the importance of this research domain.

Our four main strategic priorities are:

- Planetary Science and Astronomy, where we have a strong reputation that goes back decades.

- Space Technologies, with a particular strength in CubeSat technologies and small instruments.

- Earth Observations for societal benefit.

- Space and Remote Health.

The environment and nature are clear focuses of the work at Western Space. Can you provide examples of work you are doing in this field?

One project that we’re excited about is on multi-scale methane monitoring, which launched just over a year ago. This project is in partnership with the City of London landfill. Methane is one of the most potent greenhouse gases – about 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide, and landfills are a well-known source. The City of London, which has a methane capture system, wants to know how much methane the landfill is generating, and whether its system is capturing all that it is generating. The City is also interested in factors such as seasonal variations, to gain an understanding of how the cycle of methane emission changes over the course of the year. The monitoring programme that we have is quite unique. We call it multi-scale because we’re monitoring methane on many levels – from the ground; using an instrument on a drone that is surveying the landfill; and with satellite observations from space. These methods intersect well because the instruments that are used for each of them are different, the cadence of data collection varies, and the resolution of the measurements changes depending on the location of your instrument. This project provides an opportunity to cross-compare these different techniques and see how well they work.

In terms of nature, our current CubeSat project is called Western Skylark. It is a partnership with the Centre for Animals on the Move (CAM) – a group here at Western that studies animal movement and migration. This project is a beautiful example of how space can provide a solution to a problem in a non-intuitive way. Our colleagues at CAM have a network, called the Motus Wildlife Tracking System, of around 1,500 receivers distributed around the world. They are very simple antennas and have a little box on them containing a solar panel and a hard drive. When a tagged animal gets close, it notifies the receiver and generates a record with the time stamp and animal type. The major problem that CAM faced was that many are in hard-to-reach locations such as woods and mountains. In this situation, data would need to be physically retrieved, which could often be very difficult and take a long time. Through Western Skylark, we are putting transmitters on the Motus nodes so that they can send the data up to the satellite, and we can then relay it back to Western. This means that data can now be collected in near-real time, opening up a realm of scientific potential.

How can technologies developed by the institute be used to address challenges in other sectors, such as healthcare?

Space technologies intersect with healthcare in many ways. Keeping people alive in space comes with a set of very specific challenges. First, it is a low-resource environment far away from all sorts of diagnostic and treatment tools and people are isolated. There is also exposure to radiation and microgravity. The solutions developed for space can also benefit underserved groups such as remote Indigenous and rural communities. For example, AI systems for cough analysis can support astronaut health during missions and patient self-care during the winter flu season.

Working in space and remote health offers access to space expertise and innovation, which can be applied to pressing healthcare issues. In large countries like Canada, many people live far from high-level medical care, making in situ treatment crucial. We aim to bring care to patients within their communities, reducing expensive and difficult travel burdens.

Another signature research area in the health domain focuses on developing wearable soft robots for upper-limb rehabilitation, particularly for remote communities lacking physical therapy access. These soft robots, customised to each patient, use muscle activity sensors to detect intentions and transmit commands to actuators. The control system supports exercises with remote feedback from clinical specialists. Unlike current rigid, bulky devices, our soft garments (gloves, sleeves, shirts) are more comfortable and could be integrated into spacesuits for astronaut activities. This research also explores haptic feedback to remote clinicians to enhance telemedicine exams in remote regions.

rehabilitation

Space situational awareness is an important concern today. Can you elaborate on how the institute is focusing on this area?

Space situational awareness is important for a plethora of reasons. A major one is that low-Earth orbit, where the mega constellation satellites such as Starlink and OneWeb are being placed, is getting extremely crowded. This creates the risk of satellites crashing into each other and generating debris. Furthermore, the large number of satellites create light pollution that affects astronomers’ ability to study distant objects as telescope images are constantly contaminated by satellite trails. So, knowing just where satellites are and how bright they are is important for astronomers and satellite trackers alike.

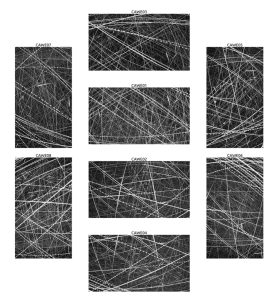

Tackling space situational awareness presents a beautiful story of how a science goal, being pursued by very passionate people, can lead to tools that are valuable in a number of different areas. For example, we have an excellent meteor group at Western that has developed the Global Meteor Network – a citizen science project where people around the world have set up low-cost, off-the-shelf cameras to examine the sky for meteors. Having more than one camera looking at a meteor allows the trajectory to be tracked to determine where in the Solar System the meteor came from. For bright meteors called fireballs, there is the exciting opportunity to get a sample return, because you then know where to collect any fallen meteorites. However, having a large number of cameras all over the world looking up also means that the software can be designed to pick out trails from satellites. Using the same methods and technology for meteors and fireballs, you can look at a bright streak in the sky, get an observation from one or more than one location, and then determine the trajectory. From this, the meteor group is able to generate catalogues of satellites in low-Earth orbit and publish them. This is extremely useful for commercial operators and space agencies like ESA and NASA.

How important is collaboration in your work?

Collaboration is absolutely essential. We are an interdisciplinary institute, which means that no one person has all the expertise. Our methane project is a great example of this. I am formally leading the project; we have an engineer who’s in charge of the instrument on the drone; we have computer scientists running the drone; and we have geographers working with the collected data from all sources. We are also working closely with the City of London, which has been a key partner.

Within the members of the institute, we have expertise from many research domains which is vital as we are often tackling interdisciplinary problems. It is also really important that we have the perspective of our partners so we can understand their needs.

What can we expect from the institute in the near future?

One of our short-term priorities is to build up our CubeSat programme. One exciting direction we’re moving in with our CubeSat programme is to use it to test new technologies in space. To this end, we are aiming to have a regular cadence of CubeSat and stratospheric balloon operations. This will allow us to rapidly advance the technology readiness levels of space hardware under development. We also have the capability of operating and communicating with satellites with our antenna ground station supporting communication in the UHF, VHF, and S-band frequencies. This could potentially be expanded to support other higher frequencies (X-band and Optical) used by satellite constellations for higher data rates in future.

Our Mission Control for remote operations will be set up by the end of 2024 to facilitate a wide range of activities, including observation planning for an orbiter around Mars. We will also be able to use it for such things as telescope and rover operations and testing remote health protocols.

Please note, this article will also appear in the 20th edition of our quarterly publication.

This post was originally published on here