Researchers uncover a possible explanation for the abrupt temperature spike in 2023: a reduction in low-level cloud cover diminishes Earth’s capacity to reflect solar radiation.

Rising sea levels, melting glaciers, and marine heatwaves—2023 broke numerous alarming records. Among them, the global mean temperature climbed to nearly 1.5°C above preindustrial levels, marking an unprecedented high. Researchers face a significant challenge in pinpointing the causes of this sudden spike. While factors such as human-driven greenhouse gas accumulation, the El Niño weather phenomenon, and natural events like volcanic eruptions explain much of the warming, they don’t fully account for it.

Notably, there remains an unexplained gap of about 0.2°C in the global temperature rise. A team from the Alfred Wegener Institute proposes a compelling hypothesis: the Earth’s surface has become less reflective due to a decline in certain types of clouds. This reduction in reflectivity may help explain the additional warming.

“In addition to the influence of El Niño and the expected long-term warming from anthropogenic greenhouse gases, several other factors have already been discussed that could have contributed to the surprisingly high global mean temperatures since 2023,” says Dr Helge Goessling, main author of the study from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI): e.g. increased solar activity, large amounts of water vapor from a volcanic eruption, or fewer aerosol particles in the atmosphere. But if all these factors are combined, there is still 0.2 degrees Celsius of warming with no readily apparent cause.

“The 0.2-degree-Celsius ‘explanation gap’ for 2023 is currently one of the most intensely discussed questions in climate research,” says Helge Goessling. In an effort to close that gap, climate modelers from the AWI and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) took a closer look at satellite data from NASA, as well as the ECMWF’s own reanalysis data, in which a range of observational data is combined with a complex weather model. In some cases, the data goes back to 1940, permitting a detailed analysis of how the global energy budget and cloud cover at different altitudes have evolved.

“What caught our eye was that, in both the NASA and ECMWF datasets, 2023 stood out as the year with the lowest planetary albedo,” says co-author Dr Thomas Rackow from the ECMWF. Planetary albedo describes the percentage of incoming solar radiation that is reflected back into space after all interactions with the atmosphere and the surface of the Earth. “We had already observed a slight decline in recent years. The data indicates that in 2023, the planetary albedo may have been at its lowest since at least 1940.” This would worsen global warming and could explain the ‘missing’ 0.2 degrees Celsius. But what caused this near-record drop in planetary albedo?

Decline in lower-altitude clouds reduces Earth’s albedo

The albedo of the surface of the Earth has been in decline since the 1970s – due in part to the decline in Arctic snow and sea ice, which also means fewer white areas to reflect back sunlight. Since 2016, this has been exacerbated by sea-ice decline in the Antarctic. “However, our analysis of the datasets shows that the decline in surface albedo in the polar regions only accounts for roughly 15 percent of the most recent decline in planetary albedo,” Helge Goessling explains.

And albedo has also dropped markedly elsewhere. In order to calculate the potential effects of this reduced albedo, the researchers applied an established energy budget model capable of mimicking the temperature response of complex climate models. What they found: without the reduced albedo since December 2020, the mean temperature in 2023 would have been approximately 0.23 degrees Celsius lower.

Implications of Lower Cloud Cover

One trend appears to have significantly affected the reduced planetary albedo: the decline in low-altitude clouds in the northern mid-latitudes and the tropics. In this regard, the Atlantic particularly stands out, i.e., exactly the same region where the most unusual temperature records were observed in 2023. “It’s conspicuous that the eastern North Atlantic, which is one of the main drivers of the latest jump in global mean temperature, was characterized by a substantial decline in low-altitude clouds not just in 2023, but also – like almost all of the Atlantic – in the past ten years.” The data shows that the cloud cover at low altitudes has declined, while declining only slightly, if at all, at moderate and high altitudes.

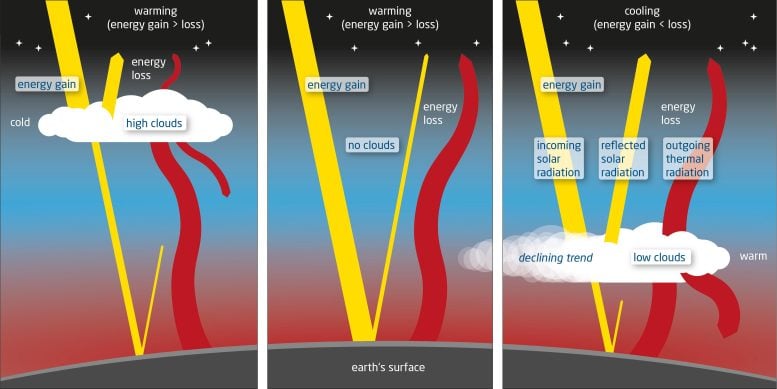

The fact that mainly low clouds and not higher-altitude clouds are responsible for the reduced albedo has important consequences. Clouds at all altitudes reflect sunlight, producing a cooling effect. But clouds in high, cold atmospheric layers also produce a warming effect because they keep the warmth emitted from the surface in the atmosphere. “Essentially it’s the same effect as greenhouse gases,” says Helge Goessling. But lower clouds don’t have the same effect. “If there are fewer low clouds, we only lose the cooling effect, making things warmer.”

But why are there fewer low clouds? Lower concentrations of anthropogenic aerosols in the atmosphere, especially due to stricter regulations on marine fuel, are likely a contributing factor. As condensation nuclei, aerosols play an essential part in cloud formation, while also reflecting sunlight themselves. In addition, natural fluctuations and ocean feedbacks may have contributed. Yet Helge Goessling considers it unlikely that these factors alone suffice and suggests a third mechanism: global warming itself is reducing the number of low clouds.

“If a large part of the decline in albedo is indeed due to feedbacks between global warming and low clouds, as some climate models indicate, we should expect rather intense warming in the future,” he stresses. “We could see global long-term climate warming exceeding 1.5 degrees Celsius sooner than expected to date. The remaining carbon budgets connected to the limits defined in the Paris Agreement would have to be reduced accordingly, and the need to implement measures to adapt to the effects of future weather extremes would become even more urgent.”

Reference: “Recent global temperature surge intensified by record-low planetary albedo” by Helge F. Goessling, Thomas Rackow and Thomas Jung, 5 December 2024, Science.

DOI: 10.1126/science.adq7280

This post was originally published on here