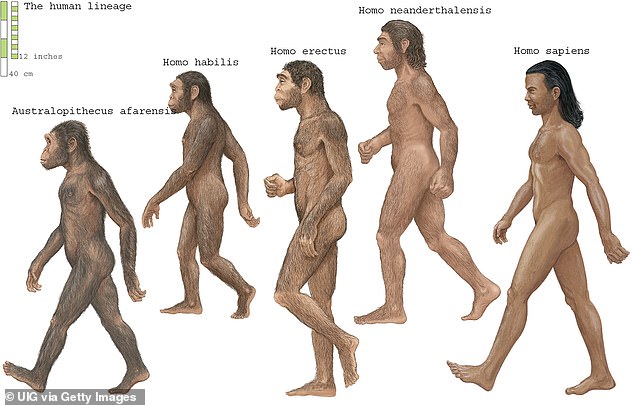

Today, only one kind of human exists – the homo sapiens.

But about 60,000 years ago we went head-to-head – and even had sex with – another species, called the Neanderthals.

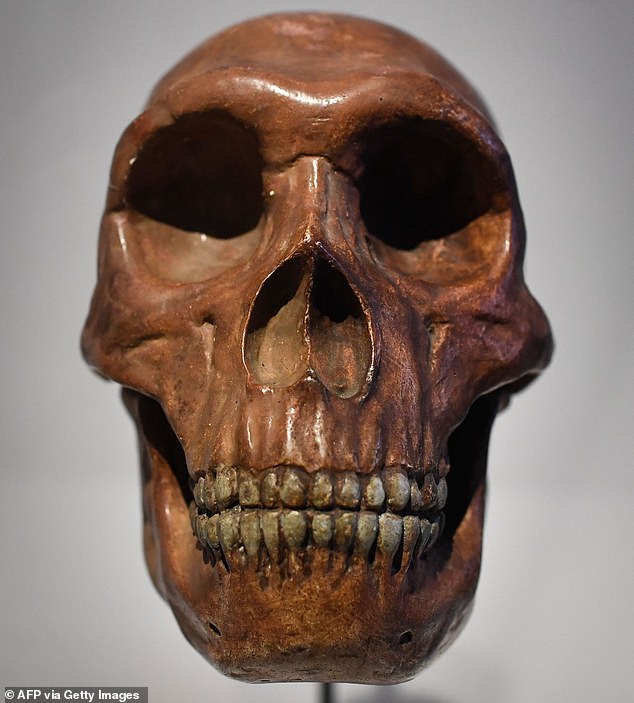

This ancient relative had large noses, strong double-arched brow ridge and relatively short and stocky bodies, skeletal evidence shows.

And although the details of Neanderthal sexual organs are not preserved in the fossil record, anatomically weren’t that different from us, it’s believed.

Researchers say that Neanderthals had penises of the same size and general shape as modern men.

Dr Andrew Merriwether, anthropologist at Binghamton University in New York, said Neanderthals and homo sapiens were ‘incredibly similar’.

‘They are pretty much identical to us in most respects, so I would assume the unpreserved soft parts would likely be the same as other humans,’ he told MailOnline.

Professor Guido Barbujani, an evolutionary anthropologist at the University of Ferrera in Italy, told MailOnline: ‘Genitalia are not preserved in fossils, and there is no way to figure out what they looked like in Neanderthals.

‘Evolution can be quite fast at times, but I doubt it may have deeply modified reproductive organs.’

Largely, the history of Neanderthals – and details about their encounters with homo sapiens – remain much of a mystery.

But we do know that homo sapiens migrated out of Africa 60,000 to 70,000 years ago to Eurasia (Europe and Asia) – where they found Neanderthals.

When the two species first encountered each other, they likely used basic verbal communication or even languages – possibly enough to understand each other.

‘Neanderthals were probably able to speak as we can infer from the morphology of some bones and from inferences we can do of their brain,’ Alessia Nava, anthropologist at the University of Rome, told MailOnline.

However, Professor Barbujani pointed out that all species of apes today ‘mate happily without verbal communication’ – apart from humans.

Marks on ancient skulls and evidence of weapons suggest Neanderthals and homo sapiens engaged in brutal fights, but there was also widespread love-making.

‘We of course assume that mating was consensual,’ Paul Pettitt, professor of archaeology at the University of Durham, told MailOnline.

‘But a sad fact of the ancient world may suggest that this was far from the truth and perhaps one “partner” had little choice in the matter.

‘Thus, in the rough and tumble of the prehistoric world perhaps mating just occurred – impromptu, with little thought or intention.

‘If it was consensual then we can certainly assume there was foreplay – even sensual kissing and cuddling.’

Chimpanzees – extant relatives of both homo sapiens and Neanderthals often indulge in this type of intimate social bonding behaviour and even hold hands, he added.

Whatever the circumstances of the two species copulating, we know they birthed successful offspring, which is why humans today have some Neanderthal DNA.

A 2020 study found the two species could produce ‘fertile and healthy’ babies with ease because they were genetically alike.

The two species started to breed with each other about 50,500 years ago and continued to do so for about 7,000 years, until Neanderthals began to die out.

Reasons for their demise vary, but experts have suggested they were vulnerable to climate change or lost violent battles with homo sapiens for resources, like food and shelter.

Professor Pettitt is one expert who contests the assumption that homo sapiens and Neanderthals were even two different species.

‘Just because the bones and brains of Neanderthals had different shapes to those of homo sapiens, doesn’t necessarily mean that the two were actually distinct biological species,’ he told MailOnline.

‘In the wider animal word there is plenty of evidence of successful interbreeding between different ‘species’.

‘We should perhaps view the human picture between 50,000 and 40,000 years ago as a mosaic of regional ‘mestizo’ populations – largely identical biologically but with distinct genetic adaptations to their differing environments.’

This post was originally published on here