This post was originally published on here

Fluids formed by surfactants is common in detergents, shampoos, cosmetics and industrial additives may look simply, but their internal structure makes them fundamentally different from water or oil. These fluids are known as wormlike micellar fluids that contain long, flexible, rod like assemblies that behave like molecular threads dispersed in water. Their ability to rearrange, break and reform under stress gives them properties that are useful in oil recovery, personal care products and material processing. Still, it makes their behaviour difficult to predict.

In soap based fluids, objects move smoothly and reach a clear terminal velocity, complex fluids that can resist motion in irregular ways. When a ball is dropped into water or cooking oil, gravity and drag quickly balance out. But in fluids such as gels, polymer solutions or concentrated soaps, the force acting on a falling or moving object may fluctuate endlessly. Scientists have long observed this different motion but lacked a precise way to map the local structures responsible for it.

This gap in understanding has practical consequences. Industries rely on stable, predictable fluid behaviour when designing products such as shampoos, drilling fluids or lotions. To design better materials, researchers need to understand what happens not just at the bulk level but in the small, often hidden regions surrounding a moving object.

New Window into Fluid Motion

Researchers at the Raman Research Institute (RRI) have now developed a method that captures this micro level behaviour with clarity. They constructed a custom device within a rheometer a machine normally used to measure how materials flow. This modified set up holds the fluid between two cylinders while a slender probe moves through it, allowing the researchers to measure the forces acting on the probe as it travels.

What sets this method apart is the integration of controlled mechanical measurements with in-situ optical imaging at the same time as the movement of the probe, the high-speed cameras document the rearrangement of local structures and the flow of fluid around it. This dual perspective allows the researchers to correlate forces acting on the probe with underlying microscopic events, providing an unprecedentedly detailed real time view of the fluid’s response to stress.

Such simplicity of setup is intentional by using a needle like probe instead of a falling object, the authors had established a system that allows them to make very precise adjustments of velocity, direction and position. This flexibility offers an opportunity to investigate many aspects of the motion of probes that are difficult to access and which often hide beneath bulk measurements.

From Smooth Motion to Rhythmic Bursts

The experiments unveiled two different regimes of fluid behaviour. At low probe velocities, the force acting on the probe remained steady over time. Within this regime the fluid behaved much like a Newtonian fluid such as waters internal structures responded smoothly to the probe’s motion. The movement produced no surprises and the drag remained constant.

But with increased velocity above some threshold, all changed. The force rose gradually and then collapsed all of a sudden repeatedly to form a so called “sawtooth” pattern. During each cycle, there was a slow build up of resistance followed by a sudden drop. It was not dissimilar from the response when an elastic band is stretched and suddenly snaps.

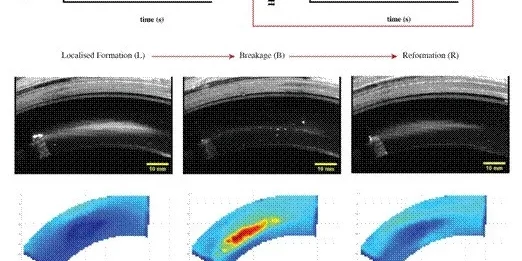

High speed imaging revealed the origin of these bursts. At higher probe speeds, a stream of fluid around the moving probe developed a tail like wake and a structure formed when micelles stretch out. As this wake grew in size until stress became strong enough for it to detach abruptly, its rapid detachment corresponded exactly with the drop in force recorded in the mechanical measurements.

Such a direct link between microscopic structure and macroscopic force is seldom found in investigations of complex fluids. Capturing these events both visually and mechanically, the researchers were able to clearly account for the rhythmic fluctuations that have mystified scientists for decades.

Why These Findings Matter

The behaviour uncovered in this study, cannot be explained by traditional bulk mechanical measurements alone. In standard tests the response of the whole fluid is averaged out, frequently obscuring the local events that control the motion of small objects within it. The results from RRI’s team show that the micro-scale structures and the way they stretch, reform or snap are key to shaping motion.

Industrial Formulations Can Be Optimised More Efficiently

Many ordinary products derive their effectiveness from the way they respond to motion, mixing or spreading. In cosmetics and personal care products, for example the shearing of lotions under the hand involves the behaviour of micellar structures. The flow of surfactant-based fluids through porous rock during oil recovery likewise involves such structural rearrangements. With a better understanding of the forces involved, engineers can design materials to flow more predictably and behave with greater consistency.

New Tool for Studying Complex Materials

The custom designed probe system provides a powerful means for the study of non-Newtonian behaviour in a variety of material classes. By varying the size, shape and velocity of the probe, one is able to examine how different structures respond to stress. Also opens up possibilities for research into polymers, gels, biological fluids and other systems in which it is local structure that holds the key to understanding their response.

Study Offers a Framework for Multi-Scale Understanding

Fluids like wormlike micelles, simply cannot be understood at a single scale and their behaviour depends simultaneously on molecular assembly, micro-scale rearrangements and large-scale flow. It illustrates a broader trend in materials science toward the combination of structural insight with the mechanical response for better predictions.

India’s rising role in soft matter research

Work at RRI illustrates an increasing contribution of India towards soft matter physics and rheology. The successful development of a novel experimental platform supported by the Department of Science and Technology reflects the expanding capacity of the country for high quality, curiosity driven research. Such efforts form the foundation for innovations that can influence both basic science and industrial applications.

The researchers envision with their technique includes the study of more systems, such as different composition surfactant solutions and probes with a range of sizes. They anticipate that new behaviours, not accessible in the present experiments will emerge with this change of scale. This is a promising direction since many phenomena of interest occur at a range of scales and examples include the settling of particles in industrial fluids and the movement of droplets in consumer products.

Understanding the behaviour of liquids at these scales will eventually enable better product design, improved predictive models and a fundamental understanding of the physics of soft materials. These findings also set the stage for future work combining experimental tools with computational modelling for a more complete picture of fluid dynamics in complex geometries. The technique developed at the Raman Research Institute gives a rare, detailed look at the behaviour of soap-based fluids around a moving object. Watching the forces the probe experiences, along with the microscopic structures that form around it, researchers uncovered a mechanism that explains long observed but poorly understood patterns.

This study shown an importance of probing materials at multiple scales and serves to illustrate the value of simple yet insightful experimentation. In an industrial sense the continued reliance on complex fluids in industries means that such research creates a much-needed link between scientific understanding and industrial application, making sense of materials encountered in everyday life.