This post was originally published on here

The origins of complex, nucleated cellular life – everything from amoebas to humans – may date back a lot further in Earth’s history than we thought.

A new study tracing the earliest steps toward complex life suggests that this transformation from simpler ancestors began almost 3 billion years ago – long before our planet had the oxygen levels needed to support a thriving eukaryotic biosphere.

That’s almost a billion years earlier than some estimates place the rise of complex cells, pointing to a surprisingly long, drawn-out evolutionary buildup rather than a rapid leap in complexity.

Related: Extreme ‘Fire Amoeba’ Smashes Record For Heat Tolerance

There are many ways to group life on Earth, but possibly the most basal distinction is between prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Prokaryotes, a group that includes bacteria and archaea, were the first life to emerge on Earth around 4 billion years ago. Prokaryotes are relatively simple, essentially consisting of a cell membrane, some rugged proteins, and free-floating DNA.

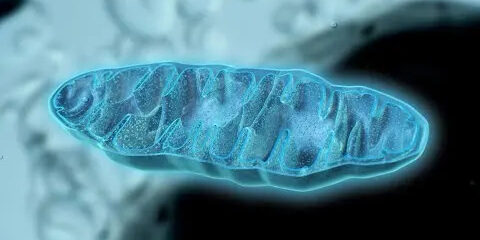

Eukaryotes, by contrast, came later and are a lot more complex, with nuclei, organelles, delicate internal membranes, and larger, more structured genomes.

YouTube Thumbnail

How much later, and the order in which these components developed, has been something of an open question for a very long time. One of the biggest unknowns is where mitochondria fit in the timeline – the so-called “powerhouses” of the cell that help convert the energy in glucose into a chemical called adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to power cellular processes.

Scientists think that mitochondria started as a free-living bacterium that took up residence inside another cell and eventually fused with it. The timing of this merger matters – whether the mitochondria came first and triggered the rest of the changes towards complexity, or whether complexity started first and the mitochondria came along later.

Advertisement

Advertisement

To figure this out, a team led by paleobiologist Christopher Kay of the University of Bristol in the UK carried out a molecular clock analysis of genes from a wide range of organisms.

Win a Space Coast Adventure Vacation

“The approach was two-fold: by collecting sequence data from hundreds of species and combining this with known fossil evidence, we were able to create a time-resolved tree of life,” says computational evolutionary biologist Tom Williams of the University of Bath in the UK.

“We could then apply this framework to better resolve the timing of historical events within individual gene families.”

A molecular clock is a method that allows scientists to estimate when organisms diverged and when traits first emerged. Basically, all lifeforms on the planet have a few things in common, such as the universal genetic code, an almost-universal set of amino acids, and a universal reliance on ATP for energy.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Scientists can estimate the rate at which mutations occur in a specific DNA sequence, compare the same sequence in multiple species, and work backwards to estimate when those species last shared an ancestor. They can also use a molecular clock to figure out when traits or gene functions first appeared.

By focusing on the differences between eukaryotes and prokaryotes, the researchers used genes from hundreds of organisms to reconstruct a timeline of the order in which eukaryotic traits emerged. They call their model CALM, an acronym for Complex Archaeon, Late Mitochondrion.

Astonishingly, some of the first genetic signatures appeared about 2.9 to 3 billion years ago, with the first detectable steps towards actin and tubulin proteins, a simple cytoskeleton, and early features of a protonucleus.

This was followed by changes that would lead to cytoplasmic membranes, organelles called the Golgi apparatus, and a diversification of gene expression systems such as RNA polymerases.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The mitochondria came relatively late to the party – appearing around 2.2 billion years ago.

But that timing coincides with the time at which Earth’s oxygen rapidly increased – suggesting that, even though eukaryotic life was well on its way before the Great Oxidation Event, it needed a little boost from environmental changes to get to where it is today.

“What sets this study apart is looking into detail about what these gene families actually do – and which proteins interact with which – all in absolute time,” Kay says.

“It has required the combination of a number of disciplines to do this: paleontology to inform the timeline, phylogenetics to create faithful and useful trees, and molecular biology to give these gene families a context.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

The research has been published in Nature.