This post was originally published on here

New University of Maryland research suggests that dinosaur parenting strategies helped transform the Mesozoic world, as “latchkey kid dinosaurs” spread into ecological niches their parents left untouched.

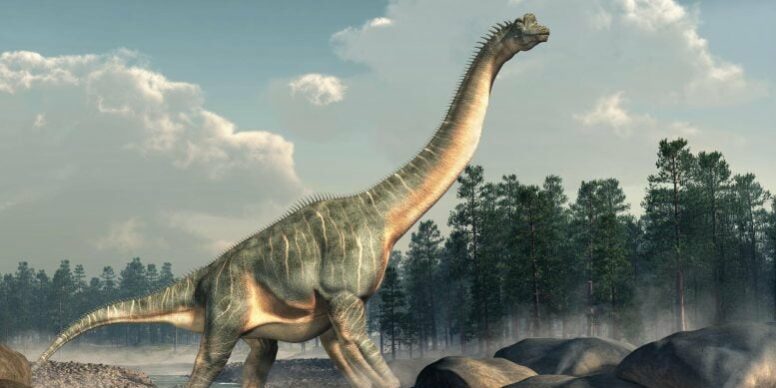

Imagine a young Brachiosaurus no bigger than a golden retriever, foraging alongside its siblings while staying alert to predators eager for an easy meal. Far away, its parents, rising more than 40 feet tall, continue their daily routines, seemingly unaffected by what happens to their vulnerable offspring.

For decades, Thomas R. Holtz Jr., a principal lecturer in the University of Maryland’s Department of Geology, has examined how dinosaurs functioned within their prehistoric environments and how those systems compare with today’s world. In his latest research, published in the Italian Journal of Geosciences, he argues that scientists have overlooked a key factor when drawing parallels between dinosaurs and modern mammals.

“A lot of people think of dinosaurs as sort of the mammal equivalents in the Mesozoic era, since they’re both the dominant terrestrial animals of their respective time periods,” Holtz said. “But there’s a critical difference that scientists didn’t really consider when looking at how different their worlds are: reproductive and parenting strategies. How animals raise their young impacts the ecosystem around them, and this difference can help scientists reevaluate how we perceive ecological diversity.”

Helicopter parents vs. latchkey kids

In mammals, young animals usually stay under close maternal care until they are nearly fully grown. According to Holtz, this extended dependence means that mammal offspring generally fill the same ecological role as their parents, relying on adults for food and protection while interacting with the same surroundings.

“You could say mammals have helicopter parents, and really, helicopter moms,” he explained. “A mother tiger still does all the hunting for cubs as large as she is. Young elephants, already among the biggest animals on the Serengeti at birth, continue to follow and rely on their moms for years. Humans are the same in that way; we take care of our babies until they’re adults.”

On the other hand, dinosaurs operated very differently. While they did provide some parental care, young dinosaurs were relatively independent. After just a few short months or a year, juvenile dinosaurs left their parents and roamed alone, watching out for each other.

Holtz pointed out a similar case in adult crocodilians, some of the closest living analogs for dinosaurs. Crocodiles guard nests and protect hatchlings for a limited period, but within a few months, juveniles disperse and live independently, taking years to reach adult size.

“Dinosaurs were more like latchkey kids,” Holtz said. “In terms of fossil evidence, we found pods of skeletons of youngsters all preserved together with no traces of adults nearby. These juveniles tended to travel together in groups of similarly aged individuals, getting their own food and fending for themselves.”

Dinosaurs’ free-range parenting style complemented the fact that they hatched eggs, forming relatively large broods in a single attempt. Because multiple offspring were born at once and reproduction occurred more frequently than in mammals, dinosaurs increased the chances of survival for their lineage without expending much effort or resources.

“The key point here is that this early separation between parent and offspring, and the size differences between these creatures, likely led to profound ecological consequences,” Holtz explained. “Over different life stages, what a dinosaur eats changes, what species can threaten it changes, and where it can move effectively also changes. While adults and offspring are technically the same biological species, they occupy fundamentally different ecological niches. So, they can be considered different ‘functional species.’”

For example, a juvenile Brachiosaurus the size of a sheep can’t reach vegetation 10 meters above the ground like a grown-up Brachiosaurus. It must feed in different areas and on different plants and face threats from carnivores that would avoid fully grown adults. As a young Brachiosaurus grows—from dog-sized to horse-sized to giraffe-sized to its final enormous proportions—its ecological role shifts continuously.

“What’s interesting here is that this completely changes how scientists view ecological diversity in that world,” Holtz said. “Scientists generally think that mammals today live in more diverse communities because we have more species living together. But if we count young dinosaurs as separate functional species from their parents and recalculate the numbers, the total number of functional species in these dinosaur fossil communities is actually greater on average than what we see in mammalian ones.”

A new window into the past

So, how could ancient ecosystems support all these functional roles? Holtz believes that two explanations could be plausible.

First, the Mesozoic world had different environmental conditions, such as warmer temperatures and higher carbon dioxide levels. These factors would have made plants more productive, generating more food energy to support more animals. Second, dinosaurs might have had somewhat lower metabolic rates than similarly sized mammals, meaning they needed less food to survive.

“Our world might actually be kind of starved in plant productivity compared to the dinosaurian one,” Holtz suggested. “A richer base of the food chain might have been able to support more functional diversity. And if dinosaurs had a less demanding physiology, their world would’ve been able to support a lot more dinosaur functional species than mammalian ones.”

Holtz believes his theories don’t necessarily indicate that dinosaur ecosystems were significantly more diverse than our own mammalian world—just that diversity might take forms scientists currently don’t recognize. He plans to continue exploring similar patterns within this framework of functional diversity across different dinosaur life stages to better understand the world they lived in and how it evolved into the one humans live in today.

“We shouldn’t just think dinosaurs are mammals cloaked in scales and feathers,” Holtz said. “They’re distinctive creatures that we’re still looking to capture the full picture of.”

Reference: “Bringing up baby: preliminary exploration of the effect of ontogenetic niche partitioning in dinosaurs versus long-term maternal care in mammals in their respective ecosystems” by Thomas R. Holtz Jr., 6 November 2025, Italian Journal of Geosciences.

DOI: 10.3301/IJG.2026.09

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.