This post was originally published on here

In August 2021, University of Chicago Prof. Oeindrila Dube began reviewing data on a first-of-its-kind police training program she helped design and implement. Its objective: improve Chicago police officers’ effectiveness in high-stress situations.

Working with a behavioral scientist and a retired police chief, she and her team had crafted a unique approach to police instruction, which they called Situational Decision-Making. Its distinctions were behavioral science strategies designed to prevent dangerous cognitive biases, an immersive video experience and real-time, peer analysis of officers’ actions during training.

In her early analysis of Chicago’s implementation, she found real reasons for hope.

“In fact, we were astonished,” said Dube, a scholar at the Harris School of Public Policy.

More than three years later, the program, known commonly as “Sit-D,” is robust and expanding.

The evaluation of Sit-D, which was implemented through the UChicago Crime Lab, showed that Sit-D-trained officers recorded a 23% reduction in uses of non-lethal force and made 23% fewer discretionary arrests—on charges such as disorderly conduct—which have little impact on public safety. Those reductions are particularly beneficial for younger officers, who typically record higher levels of the use of force and discretionary arrests.

Though the training program did not focus explicitly on racial bias, trained officers recorded 11% fewer arrests of Black civilians and a 28% reduction in discretionary arrests of Black subjects. Arrests of subjects of all other races were essentially unchanged.

The analysis found other encouraging effects of Sit-D: Trained officers incurred nearly 50% fewer days off taken for injuries on duty, while continuing the same productivity levels.

“If you just look at the narrow benefit of the cost savings to the departments from reduced days off for injury, that more than offsets the cost of the training itself,” Dube said, counting this among the training’s many benefits.

A unique approach

Designed to challenge police officers’ assumptions in stressful situations, Sit-D’s goal is to prevent adverse outcomes before they occur.

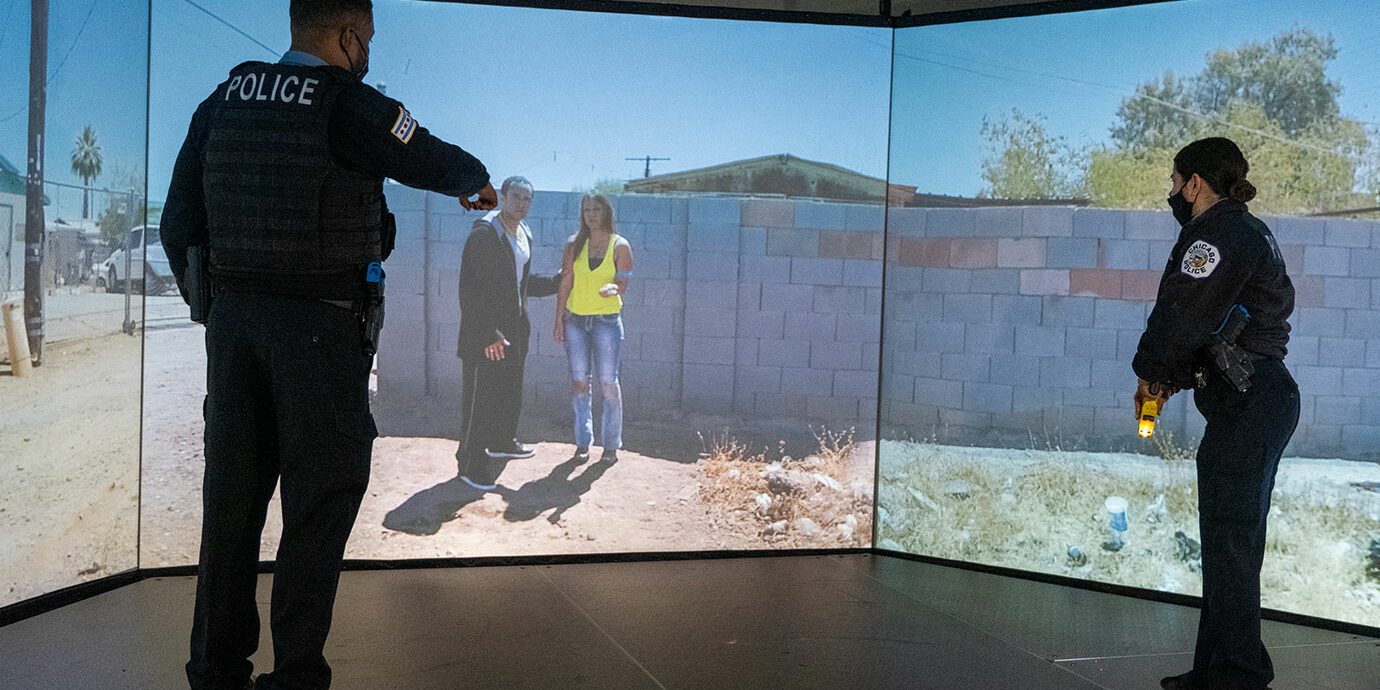

The training centers on placing officers in those stressful situations via life-size immersive video screens—known as force option simulators. In-depth discussions of officers’ thoughts and reactions accompany the video exercises.

Officers completed several scenarios: a home intruder, where a homeowner exits the house with a gun; a man holding his wife hostage, with an infant in the background; and a street stop where an aggravated man reaches into his pocket for something unknown.

Officers were shown these scenes and asked to assess them: Is the person breaking into someone’s car, or locked out of their own?

Instead of directing officers what to think when a stressful scenario presents itself, Sit-D teaches them to recognize where they might use “mental shortcuts and cognitive biases,” including over-generalizations based on earlier experiences.

The training shows officers how the “thinking traps” interfere with accurately interpreting what’s happening, how to avoid the traps and process alternative reasons for a person’s behavior—all in a very short time, Dube said.

Officers practice critical thinking, assessing a scenario and considering multiple interpretations of what’s happening in front of them. Sit-D is delivered in small classes and short sessions over several months to help officers retain material.

“It’s easy to cycle through different possibilities in a calm situation, but it’s difficult to do that under high stress,” Dube said. “Sit-D builds that muscle in officers.”

‘Everyone wins’

The training is already resonating with officers in the program. Course evaluations showed that 93% of trained officers said Sit-D was useful for their work; a further 86% said they were enthusiastic about Sit-D.

“We like to think about training the whole officer—physical skills, constitutional and community policing, officer wellness,” said Dan Godsel, who as a commander, led Chicago Police officer training when Sit-D was launched in 2020. “Above everything else was the fact that we consistently heard the officers saying this was practical training that they could start to use right away, that it was having a direct, positive impact,”

Chicago Police Sgt. Thomas Gaynor, a trainer during Sit-D, noticed that “it was more like the officers were de-briefing themselves” on their actions and decisions after completing its video training segments.

“They came to conclusions themselves,” he added. “And if someone comes to their own conclusion about what they did well and what they need to do differently, you’re almost all the way home.”

Several months after training, Gaynor recalled, an officer told a trainer that Sit-D likely saved his life during a shooting in which one of his partners was killed and another was severely wounded.

“The lessons learned in this class increase officer safety,” Gaynor said. “It keeps the public safer. I think it reduces the risk of complaints and civil liabilities for our officers. Everyone wins.”

Sit-D is also generating interest among law enforcement agencies outside Chicago—in November, the program was adopted by the Ohio Peace Officers Training Academy for implementation across the state of Ohio.

Dube is optimistic about the future of the training.

“I think the training will be able to reach lots of law enforcement officers in lots of departments of different sizes and scales,” Dube said. “Anytime we have been in a room with a police department for the first time and they’ve heard the results, it’s incredibly exciting for them and they are extremely enthusiastic about Sit-D and what it could do for them.”

Adapted from an article originally published on the Harris School of Public Policy website.