This post was originally published on here

Glaciers worldwide are racing toward extinction, with warming dictating whether thousands survive—or vanish forever.

- A major new study led by ETH Zurich has, for the first time, estimated how many of the world’s glaciers are likely to survive through the end of this century and how long each one is expected to last.

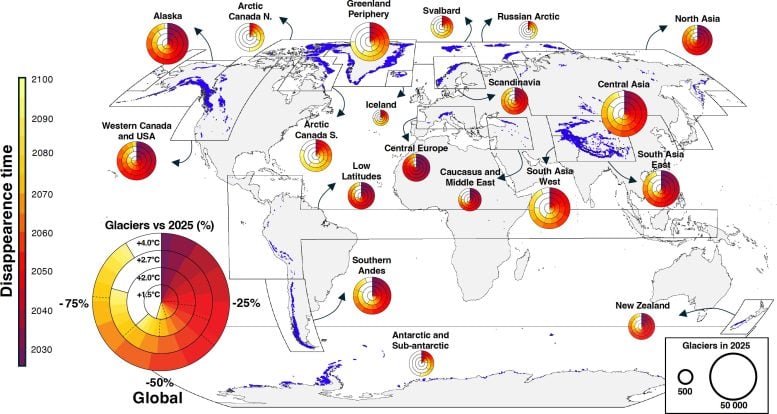

- The results show a dramatic difference depending on global warming levels. With a temperature rise of +4.0 °C, only about 18,000 glaciers would still exist by 2100. If warming is limited to +1.5 °C, roughly 100,000 glaciers would remain.

- The team also introduced the concept of “Peak Glacier Extinction,” the moment when yearly glacier loss reaches its highest point. At +1.5 °C this peak arrives around 2041 with about 2,000 glaciers disappearing in that year. Under +4 °C, the peak shifts to 2055 and the annual number of vanishing glaciers climbs to about 4,000.

Glaciers around the world are shrinking rapidly. In some places, they are on track to disappear entirely. When scientists look specifically at how many individual glaciers are vanishing, they find that the Alps could hit their highest rate of glacier loss sometime between 2033 and 2041. How much the planet warms will determine whether this period becomes the moment when more glaciers vanish than at any other time. On a global level, the maximum rate of glacier loss is expected roughly ten years later and could climb from about 2,000 to as many as 4,000 glaciers disappearing each year.

Alps face extreme glacier losses by 2100

In the Alps, the projections are especially severe. If current climate policies lead the world toward a temperature increase of +2.7 °C, only around 110 glaciers would still exist in Central Europe by 2100, which is just 3 percent of the number today. At +4 °C of warming, that figure falls to about 20 glaciers. Even medium-sized glaciers, such as the Rhône Glacier, would shrink to tiny pieces of ice or disappear altogether. Under this high-warming scenario, the large Aletsch Glacier would break apart into several smaller segments.

These changes continue a trend that ETH Zurich scientists have already tracked over the past decades, and that trend is still ongoing: they recently showed that from 1973 to 2016, more than 1,000 glaciers vanished in Switzerland alone (cf. Annals of Glaciology).

[embedded content]

A new global count of disappearing glaciers

An international team of researchers from ETH Zurich, the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research (WSL), and the Vrije Universiteit Brussel has used these and other findings to build a comprehensive new picture of glacier futures. In a landmark study, they calculated for the first time how many glaciers across the planet disappear each year, how many are likely to last until the end of this century, and for how long they can be expected to survive.

“For the first time, we’ve put years on when every single glacier on Earth will disappear,” says Lander Van Tricht, lead author of the study published today (December 15, 2025) in Nature Climate Change.

Earlier studies mostly focused on how much total ice mass and surface area are being lost. In contrast, the ETH Zurich-led team concentrates on the number of glaciers that are disappearing, where they are located, and the timing of their disappearance. Their results show that regions with many small glaciers at relatively low elevations or close to the equator are especially at risk. This group includes the Alps, the Caucasus, the Rocky Mountains, and parts of the Andes and African mountain ranges situated in low latitudes.

“In these regions, more than half of all glaciers are expected to vanish within the next ten to twenty years,” says Van Tricht, a researcher at ETH Zurich’s Chair of Glaciology and the WSL.

How many glaciers can be saved in different warming scenarios?

How fast glaciers retreat is strongly linked to the level of global warming. To explore this, the scientists used three state-of-the-art global glacier models and tested several different climate futures. For the Alps, they found that if warming is limited to +1.5 °C, 12 percent of glaciers would still be present by 2100 (roughly 430 out of about 3,000 in 2025). At +2.0 °C, the share drops to around 8 percent, or about 270 glaciers, and at +4 °C only about 1 percent, or 20 glaciers, are projected to remain.

For context, the team also examined other major mountain regions. In the Rocky Mountains, about 4,400 glaciers would still exist under the 1.5 °C scenario, which corresponds to around 25 percent of today’s roughly 18,000 glaciers. At +4 °C, however, only about 101 glaciers would remain, a 99 percent loss. In the Andes and Central Asia, roughly 43 percent of glaciers would survive at 1.5 °C. Under a +4 °C scenario, the picture changes dramatically: in the Andes, only around 950 glaciers would still be present, a 94 percent loss, and in Central Asia, about 2,500 glaciers would remain, a 96 percent decline. Overall, the projections suggest that with global warming of +4.0 °C, only about 18,000 glaciers would survive worldwide, compared with around 100,000 in a +1.5 °C world.

The study also makes clear that glacier numbers are falling everywhere. There is no remaining region where glaciers are not in numerical decline. Even in the Karakoram region of Central Asia, where some glaciers briefly advanced after the turn of the millennium, the models indicate that glaciers are expected to retreat in the future.

Peak Glacier Extinction and what it reveals

In this research, the ETH Zurich group introduces the concept of “Peak Glacier Extinction.” This term refers to the moment when the number of glaciers disappearing in a single year reaches its highest point. After that peak, the yearly loss rate decreases simply because many of the smaller glaciers have already vanished. From the perspective of climate policy, this distinction is important. Even though the annual number of disappearing glaciers drops after the peak, the overall shrinking of glacier ice continues.

The scientists calculated this peak for different levels of warming. With a +1.5 °C rise in global temperature, as targeted in the Paris Agreement, Peak Glacier Extinction would occur around 2041, at a time when about 2,000 glaciers would vanish in just one year. Under a +4 °C warming scenario, the peak shifts to around 2055, and the annual number of disappearing glaciers roughly doubles to approximately 4,000. It may appear counterintuitive that the peak occurs later under stronger warming. The explanation is that in a hotter climate, small glaciers disappear entirely, and larger glaciers also reach the point where they vanish. Being able to capture the complete loss of even very large glaciers is one of the main advantages of this new approach.

The ETH Zurich team shows that at +4 °C, the number of glaciers that disappear at the peak is twice as high as in a +1.5 °C world. In the 1.5-degree scenario, about half of today’s glaciers are expected to survive. At +2.7 °C, only around one-fifth remain, and at +4 °C, only about one-tenth. This means that every tenth of a degree of additional warming influences how many glaciers can be preserved. “The results underline how urgently ambitious climate action is needed,” says Daniel Farinotti, co-author and ETH Zurich Professor of Glaciology.

What disappearing glaciers mean for people and places

What does the retreat of glaciers mean for societies, cultures, and economies? This new way of looking at glacier loss opens up fresh perspectives for political decision-makers, businesses, and cultural institutions. Earlier work mainly examined changes in glacier mass and volume, which are crucial for estimating sea-level rise and managing water resources.

“The melting of a small glacier hardly contributes to rising seas. But when a glacier disappears completely, it can severely impact tourism in a valley,” says Lander Van Tricht.

The new analysis does more than indicate when and where glaciers will vanish. It also offers practical information that can help governments, local communities, the tourism industry, and natural hazard managers prepare for a future with less snow and ice, and more variable water supplies.

Against this backdrop, ETH Zurich researchers are also participating in projects such as the Global Glacier Casualty List, which is designed to record the names and histories of glaciers that have already disappeared, including the Birch and Pizol glaciers. “Every glacier is tied to a place, a story and people who feel its loss,” says Van Tricht. “That’s why we work both to protect the glaciers that remain and to keep alive the memory of those that are gone.”

Reference: “Peak Glacier Extinction in the mid-twenty-first century” 15 December 2025, Nature Climate Change.

DOI: 10.1038/s41558-025-02513-9

Financial support from the Research Foundation—Flanders through an Odysseus Type II project (grant no. G0DCA23N; ‘GlaciersMD’ project). H.Z. and R.A. were also funded by the European Research Council under the Horizon Framework research and innovation programme of the European Union (grant no. 101115565; ‘ICE3’ project). Additionally, H.Z., M.H. and D.F. were supported by the Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme of the European Union (PROTECT project; grant no. 869304). D.R.R. received support from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (grant nos 80NSSC20K1296 and 80NSSC20K1595), and D.R.R. and B.T. received support from the National Park Service (grant no. P22AC02208). L.S. is the recipient of a DOC Fellowship of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (no. 25928). L.S., P.S. and F.M. received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 101003687). P.S. and F.M. received funding from the Austrian Climate Research Programme—14th call, under grant agreement no. KR21KB0K00001 (HyMELT-CC), and from ESA’s ‘Digital Twin Component for Glaciers’ project (grant no. 4000146160/24/I-KE).

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.