This post was originally published on here

Astronomers have used multiple spacecraft to create the first map of the Sun’s outer “edge.” That surface of sorts plays a crucial role in generating the solar wind as well as space weather at Earth.

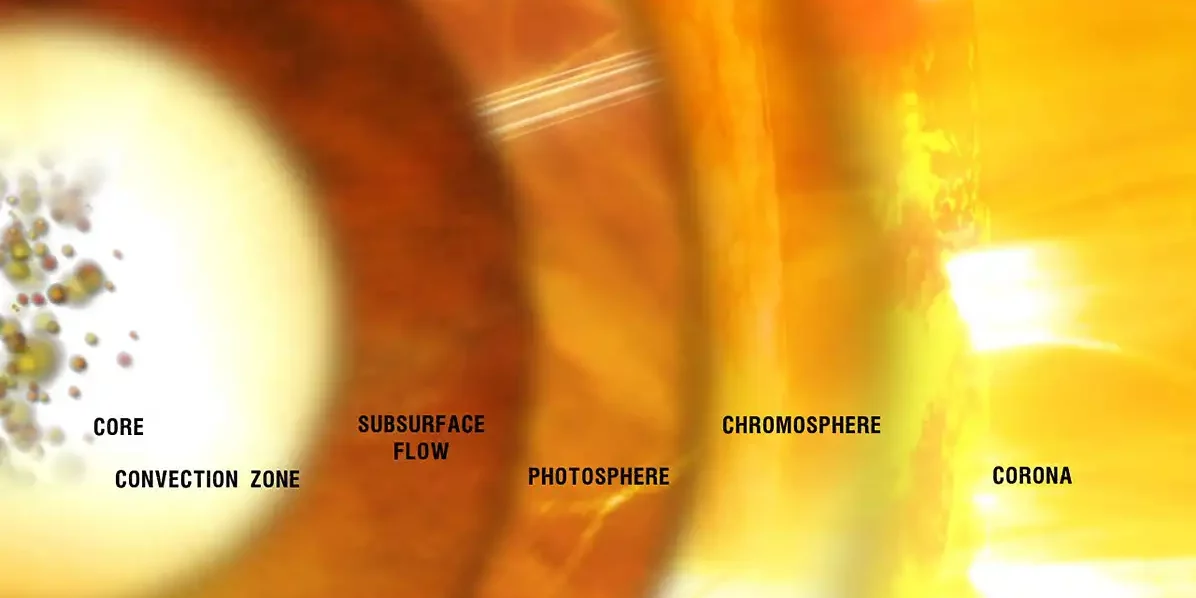

The Sun does not stop at its visible surface, the photosphere. That’s simply the bottom layer of a sprawling atmosphere that stretches its magnetic tendrils many millions of kilometers into the solar system.

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

The outer layer of the Sun’s atmosphere — its corona — is home to a crucial boundary, known as the Alfvén surface. It represents a point of no return, the place where the outward speed of material escaping from the Sun exceeds the speed of local magnetic waves. In other words, material at the Alfvén surface is no longer magnetically connected to the Sun and is free to stream past the planets as the solar wind.

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe has dived directly into the corona, coming within 6.2 million km of the photosphere, and has plunged past the Alfvén surface multiple times since its first crossing in 2021. But defining that boundary has been trickier than scientists first thought it would be. “Parker Solar Probe data from deep below the Alfvén surface could help answer big questions about the Sun’s corona, like why it’s so hot,” says lead author Sam Badman (Center for Astrophysics, Harvard & Smithsonian). “But to answer those questions, we first need to know exactly where the boundary is.”

To do that, first Badman’s team looked at in-situ solar wind data from multiple spacecraft, including Parker and the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter. They then worked backwards to reconstruct a the environment that wind must have blown from, leading to a theoretical map of the Alfvén surface. The team compared the map with Parker’s numerous boundary crossings.

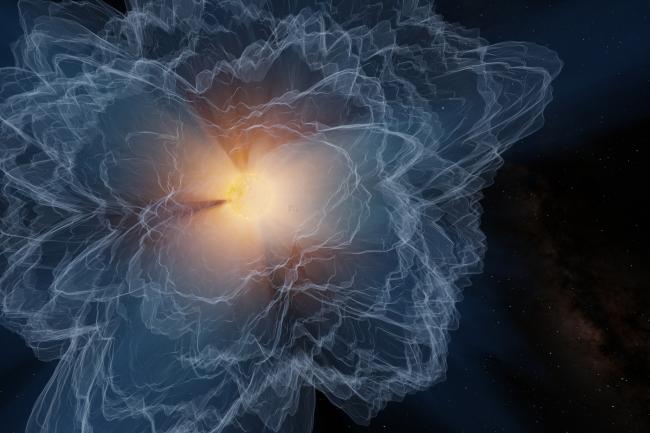

Center for Astrophysics / Melissa Weiss

The map reveals the Sun to be such a dynamic place that the boundary is constantly shifting. “As the Sun goes through activity cycles, what we’re seeing is that the shape and height of the Alfvén surface around the Sun is getting larger and also spikier,” Badman says. “That’s actually what we predicted in the past, but now we can confirm it directly.”

The team’s findings cover half a solar cycle. Published in Astrophysical Journal Letters, the results also show that the Alfvén surface is highly asymmetric and often corrugated, becoming rougher and more distorted toward solar maximum. During Solar Cycle 25, the height of the Alfvén surface varied by up to 30%.

“These results are important for our understanding of space weather, as the solar wind forms the background through which all space-weather events propagate,” says Daniel Verscharen (University College London), who was not involved in the research. Mathew Owens (University of Reading, UK), who was also not involved in the study, agrees, saying that the solar wind “has a modulating effect on the most extreme solar storms and is key to providing accurate forecasts.”

Badman’s team also found evidence that explosive detonations, known as coronal mass ejections (CMEs), leave behind wakes in the solar wind that survive for quite a long time. “This could have interesting implications for space weather, given that CMEs are particularly strong when they follow each other in quick succession,” says Verscharen.

However, there’s more to these results than just space weather. “In my view, the most interesting aspect of this work is the finding that the Alfvén surface can be farther away from the Sun than previously thought,” says Verscharen. A more distant Alfvén surface leads to a greater loss of angular momentum, meaning the Sun’s rotation will slow more quickly.

“This study suggests that this braking of the Sun’s rotation is at times stronger than previously thought,” says Verscharen. “This has important implications for our understanding of the Sun’s overall history, as well as the evolution of stars in general.”