This post was originally published on here

About ten years ago, researchers began exploring a bold idea: using bioluminescent light to see what the brain is doing in real time. Instead of shining light onto brain tissue from the outside, they wondered whether neurons could be made to glow on their own.

“We started thinking: ‘What if we could light up the brain from the inside?'” said Christopher Moore, a professor of brain science at Brown University. “Shining light on the brain is used to measure activity — usually through a process called fluorescence — or to drive activity in cells to test what role they play. But shooting lasers at the brain has down sides when it comes to experiments, often requiring fancy hardware and a lower rate of success. We figured we could use bioluminescence instead.”

Building the Bioluminescence Hub

That idea helped launch the Bioluminescence Hub at Brown University’s Carney Institute for Brain Science in 2017. Supported by a major grant from the National Science Foundation, the hub brought together collaborators including Moore (associate director of the Carney Institute), Diane Lipscombe (the institute’s director), Ute Hochgeschwender (at Central Michigan University), and Nathan Shaner (at the University of California San Diego).

The team set out to create and share new neuroscience tools by giving cells in the nervous system the ability to produce light and respond to it.

A New Tool for Watching Neurons Glow

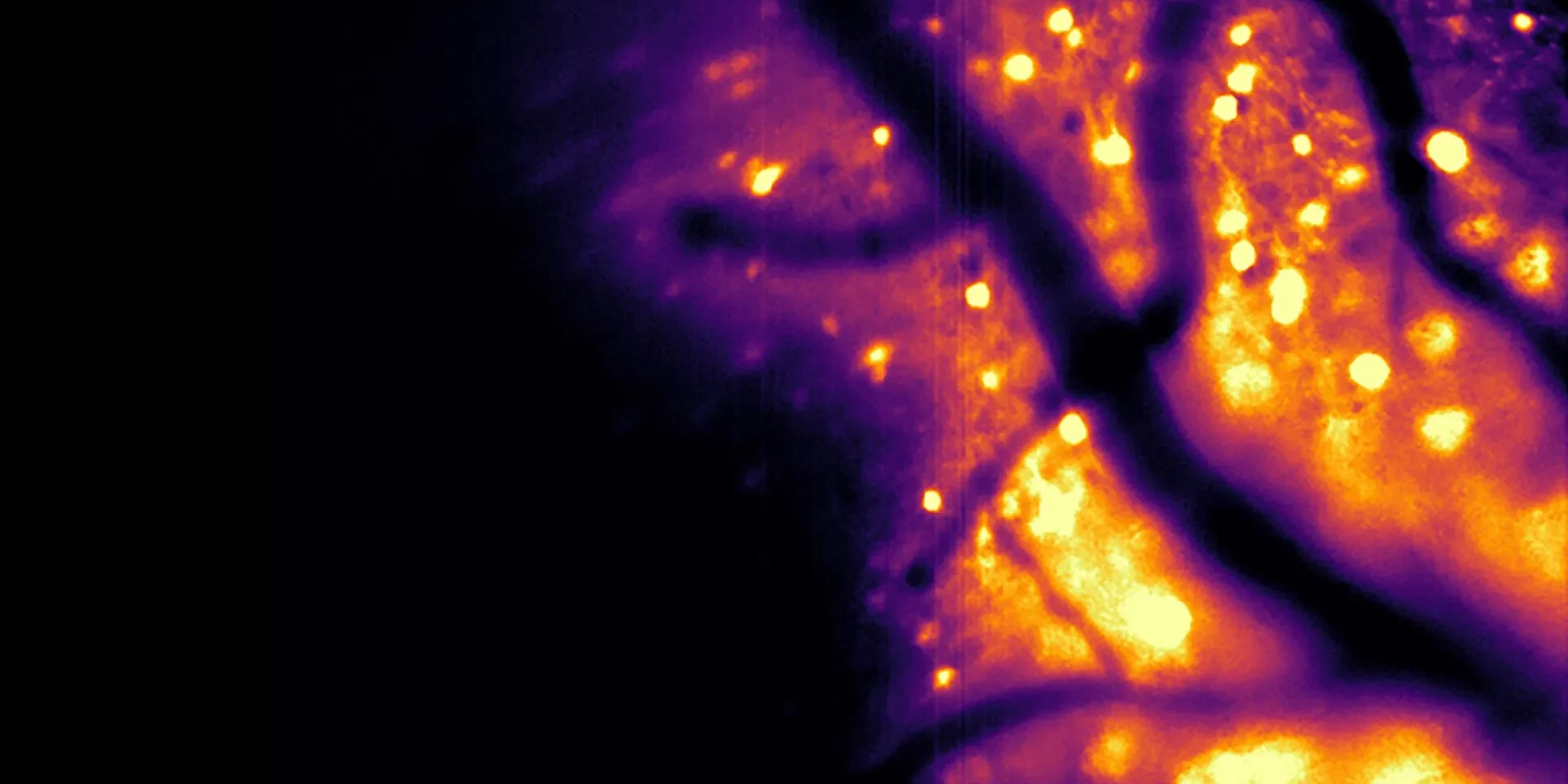

In a study published in Nature Methods, the researchers described a new bioluminescent imaging tool they developed. Known as the Ca2+ BioLuminescence Activity Monitor — or “CaBLAM,” for short — the tool can capture activity within individual cells and even smaller cellular regions at high speed. It works effectively in mice and zebrafish, supports recordings that last for hours, and does not require any external light source.

Moore said Shaner, an associate professor of neuroscience and pharmacology at U.C. San Diego, led the effort to design the molecular device behind CaBLAM. “CaBLAM is a really amazing molecule that Nathan created,” Moore said. “It lives up to its name.”

Why Measuring Brain Activity Matters

Tracking the activity of living brain cells is critical for understanding how organisms function, Moore explained. Today, the most common way to do this relies on fluorescence-based genetically encoded calcium-ion indicators.

“In the way fluorescence works, you shine light beams at something, and you get a different wavelength of light beams back,” said Moore, who directs the Bioluminescence Hub. “You can make that process calcium-sensitive so you can get proteins that will shift back a different amount or different color of light, depending on whether or not calcium is present, with a bright signal.”

Although fluorescence techniques are widely used, Moore said they come with major drawbacks. Prolonged exposure to intense external light can harm brain cells. Over time, that illumination can also alter the fluorescent molecules themselves so they no longer emit enough light, a problem known as photobleaching that limits how long experiments can run. In addition, delivering light to the brain requires equipment like lasers and optical fibers, which makes experiments more invasive.

Why Bioluminescence Offers Clear Advantages

Bioluminescent imaging works differently. Light is generated when an enzyme breaks down a specific small molecule, meaning no bright external light is needed. As a result, there is no photobleaching and no phototoxic damage, making the approach safer for delicate brain tissue.

It also produces cleaner images.

“Brain tissue already glows faintly on its own when hit by external light, creating background noise,” Shaner said. “On top of that, brain tissue scatters light, blurring both the light going in and the signal coming back out. This makes images dimmer, fuzzier, and harder to see deep inside the brain. The brain does not naturally produce bioluminescence, so when engineered neurons glow on their own, they stand out against a dark background with almost no interference. And with bioluminescence, the brain cells act like their own headlights: You only have to watch the light coming out, which is much easier to see even when scattered through tissue.”

Moore noted that scientists have discussed using bioluminescence to study brain activity for decades, but until now, no one had succeeded in making the light bright enough for detailed imaging.

The Insights That Made CaBLAM Possible

“The current paper is exciting for a lot of reasons,” Moore said. “These new molecules have provided, for the first time, the ability to see single cells independently activated, almost as if you’re using a very special, sensitive movie camera to record brain activity while it’s happening.”

Using CaBLAM, researchers can observe how a single neuron behaves inside a living animal, including activity within different parts of the cell. In the study, the team reported a continuous five-hour recording session, something that would not be possible with traditional fluorescence-based methods.

“For studying complex behavior or learning, bioluminescence allows one to capture the entire process, with less hardware involved,” Moore said.

Beyond Imaging the Brain

The CaBLAM project is part of a larger effort at the hub to invent new ways to observe and control brain activity. One experiment involves a living cell sending out a flash of light that a nearby cell can detect, allowing neurons to communicate using light itself (what Moore calls, “rewiring the brain with light”). The team is also developing techniques that use calcium to regulate cellular activity.

As these projects evolved, the researchers realized they all depended on having brighter and more effective calcium sensors. That need has become a central focus of the hub’s work, Moore said.

“We made sure that as a center that’s trying to push the field forward, we created the necessary component pieces,” Moore said.

A Tool With Broader Potential

Moore believes CaBLAM could eventually be applied beyond neuroscience to study activity in other parts of the body.

“This advance allows a whole new range of options for seeing how the brain and body work,” Moore said, “including tracking activity in multiple parts of the body at once.”

He added that the achievement highlights the strength of collaborative research. At least 34 scientists contributed to the project, representing Bioluminescence Hub partners such as Brown University, Central Michigan University, U.C. San Diego, the University of California Los Angeles, and New York University. The work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation.