This post was originally published on here

Using AI, researchers identified one tiny molecular interaction that viruses need to infect cells. Disrupting it stopped the virus before infection could begin.

Washington State University scientists have uncovered a method to interfere with a key viral protein, stopping viruses from getting inside cells where they can cause disease. The discovery points toward a possible new strategy for developing antiviral treatments in the future.

The work, published in the journal Nanoscale, involved researchers from the School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering and the Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Pathology. Together, they identified and disrupted a specific molecular interaction that herpes viruses depend on to enter cells.

“Viruses are very smart,” said Jin Liu, corresponding author of the study and a professor in the School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering. “The whole process of invading cells is very complex, and there are a lot of interactions. Not all of the interactions are equally important — most of them may just be background noise, but there are some critical interactions.”

Targeting the Protein Viruses Use to Break In

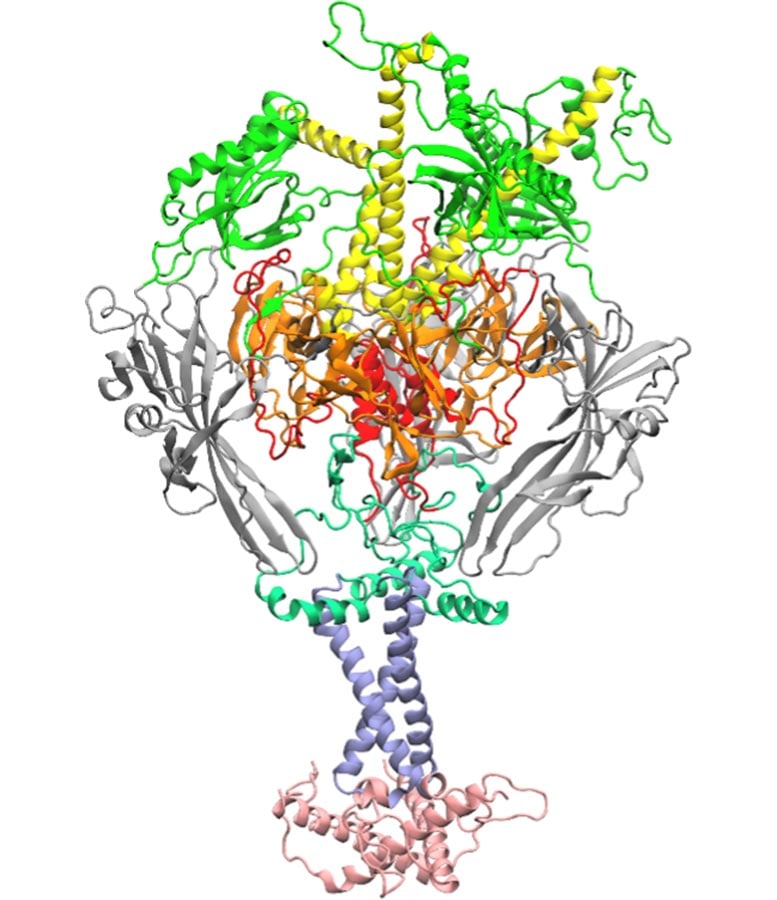

The researchers focused on a viral “fusion” protein, which herpes viruses use to attach to cells and merge with them, triggering infection and disease. Scientists still lack a clear understanding of how this large and complicated protein changes shape to allow viruses inside cells. This limited knowledge is one reason vaccines for many common herpes viruses have remained elusive.

How AI Narrowed Down Thousands of Possibilities

To tackle this challenge, the team turned to artificial intelligence and molecular scale simulations. Professors Prashanta Dutta and Jin Liu analyzed thousands of possible interactions within the fusion protein to find a single amino acid that plays a central role in viral entry. They designed an algorithm to examine interactions among amino acids, the basic building blocks of proteins, and then applied machine learning to sort through the data and identify which interactions mattered most.

A Single Mutation That Blocks Infection

Once the key amino acid was identified, laboratory experiments led by Anthony Nicola from the Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Pathology put the findings to the test. By altering that one amino acid, the researchers found that the virus could no longer successfully fuse with cells. As a result, the herpes virus was effectively prevented from entering the cells.

According to Liu, the computational work was essential because testing even one interaction in the lab can take months. Narrowing the focus ahead of time made the experimental phase far more efficient.

“It was just a single interaction from thousands of interactions. If we don’t do the simulation and instead did this work by trial and error, it could have taken years to find,” said Liu. “The combination of theoretical computational work with the experiments is so efficient and can accelerate the discovery of these important biological interactions.”

What Scientists Still Need to Understand

Although the team confirmed the importance of this specific interaction, many questions remain about how changing one amino acid affects the structure of the entire fusion protein. The researchers plan to continue using simulations and machine learning to better understand how small molecular changes influence the protein at larger scales.

“There is a gap between what the experimentalists see and what we can see in the simulation,” said Liu. “The next step is how this small interaction affects the structural change at larger scales. That is also very challenging for us.”

Reference: “Modulation of specific interactions within a viral fusion protein predicted from machine learning blocks membrane fusion” by Ryan E. Odstrcil, Albina O. Makio, McKenna A. Hull, Prashanta Dutta, Anthony V. Nicola and Jin Liu, 4 November 2025, Nanoscale.

DOI: 10.1039/D5NR03235K

In addition to Liu, Dutta and Nicola, the project was conducted by PhD students Ryan Odstrcil, Albina Makio, and McKenna Hull. The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.