This post was originally published on here

A nearly invisible material made mostly of air could redefine how windows stop heat and save energy.

Physicists at the University of Colorado Boulder have created a new type of window insulation that could significantly improve energy efficiency in buildings around the world—and it behaves much like a sophisticated version of Bubble Wrap.

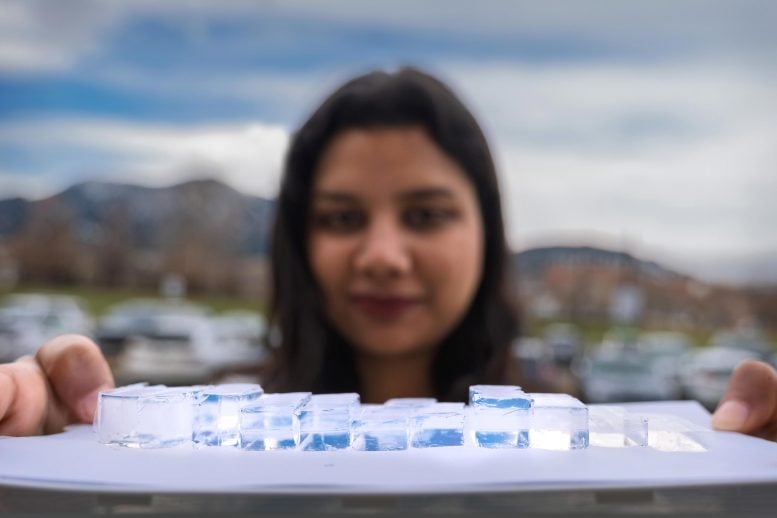

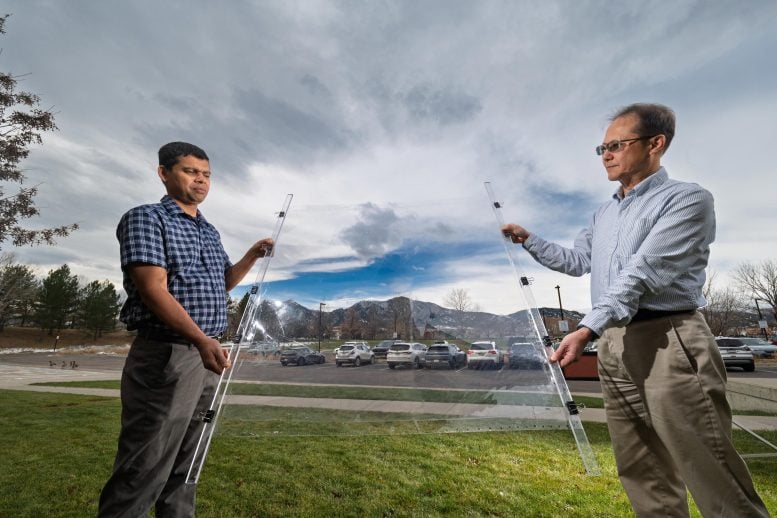

The material, known as Mesoporous Optically Clear Heat Insulator, or MOCHI, can be produced as thick panels or thin sheets designed to attach to the inside of windows. At this stage, MOCHI is made only in laboratory settings and is not yet available to the public. Even so, researchers say it is durable and nearly completely transparent.

That clarity allows light to pass through without noticeably altering the view, a major advantage over many existing insulation options.

“To block heat exchange, you can put a lot of insulation in your walls, but windows need to be transparent,” said Ivan Smalyukh, senior author of the study and a professor of physics at CU Boulder. “Finding insulators that are transparent is really challenging.”

Smalyukh and his colleagues published their findings in Science on December 11.

Why Windows Are a Major Energy Challenge

Buildings of all sizes, from single-family homes to large office towers, use roughly 40% of the energy produced worldwide. A significant portion of that energy is lost when heat escapes through windows during cold weather or enters buildings during hot conditions.

The researchers developed MOCHI with the goal of reducing that constant transfer of heat.

MOCHI is based on a silicone gel with a unique internal structure. Inside the gel is a dense network of microscopic pores that are far narrower than the width of a human hair. These air-filled spaces are so effective at stopping heat that a MOCHI sheet just 5 millimeters thick can allow someone to hold a flame against it without being burned.

“No matter what the temperatures are outside, we want people to be able to have comfortable temperatures inside without having to waste energy,” said Smalyukh, a fellow at the Renewable And Sustainable Energy Institute (RASEI) at CU Boulder.

Bubble Magic and Microscopic Air Control

Smalyukh explained that MOCHI’s performance depends on carefully shaping and arranging its tiny air pockets.

The new material shares some similarities with aerogels, which are widely used for insulation today. (NASA uses aerogels inside its Mars rovers to keep electronics warm). Aerogels also contain air-filled pores, but those pores are randomly distributed and tend to scatter light. As a result, aerogels often appear cloudy and are sometimes described as “frozen smoke.”

Rather than following that approach, the research team set out to design a material that combines strong insulation with optical clarity.

To create MOCHI, the scientists add surfactant molecules to a liquid solution. These molecules naturally cluster into thin, thread-like structures, similar to the way oil and vinegar separate when mixed. Silicone molecules in the solution then attach themselves to the surface of those threads.

In later steps, the researchers remove the detergent-based structures and replace them with air. What remains is a silicone framework surrounding an intricate system of extremely small, air-filled channels. Smalyukh likens the complex arrangement to a “plumber’s nightmare.”

Overall, air accounts for more than 90% of MOCHI’s total volume.

How MOCHI Slows the Flow of Heat

Heat moves through gases in a way that resembles a game of pool. When gas molecules gain energy, they collide with one another and transfer heat through those impacts.

Inside MOCHI, however, the pores are so small that gas molecules cannot freely collide. Instead, they repeatedly strike the walls of the pores, which greatly limits how much heat can pass through the material.

“The molecules don’t have a chance to collide freely with each other and exchange energy,” Smalyukh said. “Instead, they bump into the walls of the pores.”

Despite its insulating strength, MOCHI reflects only about .2% of incoming light, allowing nearly all visible light to pass through.

Future Applications and Commercial Potential

The research team believes the material could be used in a wide range of technologies beyond windows. One possibility is a system that captures heat from sunlight and converts it into affordable, sustainable energy.

“Even when it’s a somewhat cloudy day, you could still harness a lot of energy and then use it to heat your water and your building interior,” Smalyukh said.

MOCHI is not expected to reach the market anytime soon. Producing the material currently requires a slow and labor-intensive laboratory process. Smalyukh is optimistic, however, that manufacturing methods can be simplified over time. The materials used to create MOCHI are relatively inexpensive, which supports its potential for future commercialization.

For now, the outlook for MOCHI remains promising, much like the clear view through a window treated with this innovative insulating material.

Reference: “Mesoporous optically clear heat insulators for sustainable building envelopes” by Amit Bhardwaj, Blaise Fleury, Bohdan Senyuk, Eldho Abraham, Jan Bart ten Hove, Taewoo Lee, Vladyslav Cherpak and Ivan I. Smalyukh, 11 December 2025, Science.

DOI: 10.1126/science.adx5568

Co-authors of the new study include Amit Bhardwaj, Blaise Fleury, Eldo Abraham and Taewoo Lee, postdoctoral research associates in the Department of Physics at CU Boulder. Bohdan Senyuk, Jan Bart ten Hove, and Vladyslav Cherpak, former postdoctoral researchers at CU Boulder, also served as co-authors.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.