This post was originally published on here

A scientist based in Southern Utah has collaborated with Nagoya University in Japan to publish a study that could explain the potential benefits of molecular hydrogen therapy.

“The Rieske iron-sulfur protein is a primary target of molecular hydrogen” is a study from Dr. Tyler W. LeBaron of Southern Utah University, as well as Dr. Shuto Negishi, Dr. Mikako Ito and Dr. Kinji Ohno of Nagoya University, according to a press release from Nagoya University.

LeBaron sat down with St. George News to discuss the study and reflect on his career. To start, LeBaron said, hydrogen is an important building block.

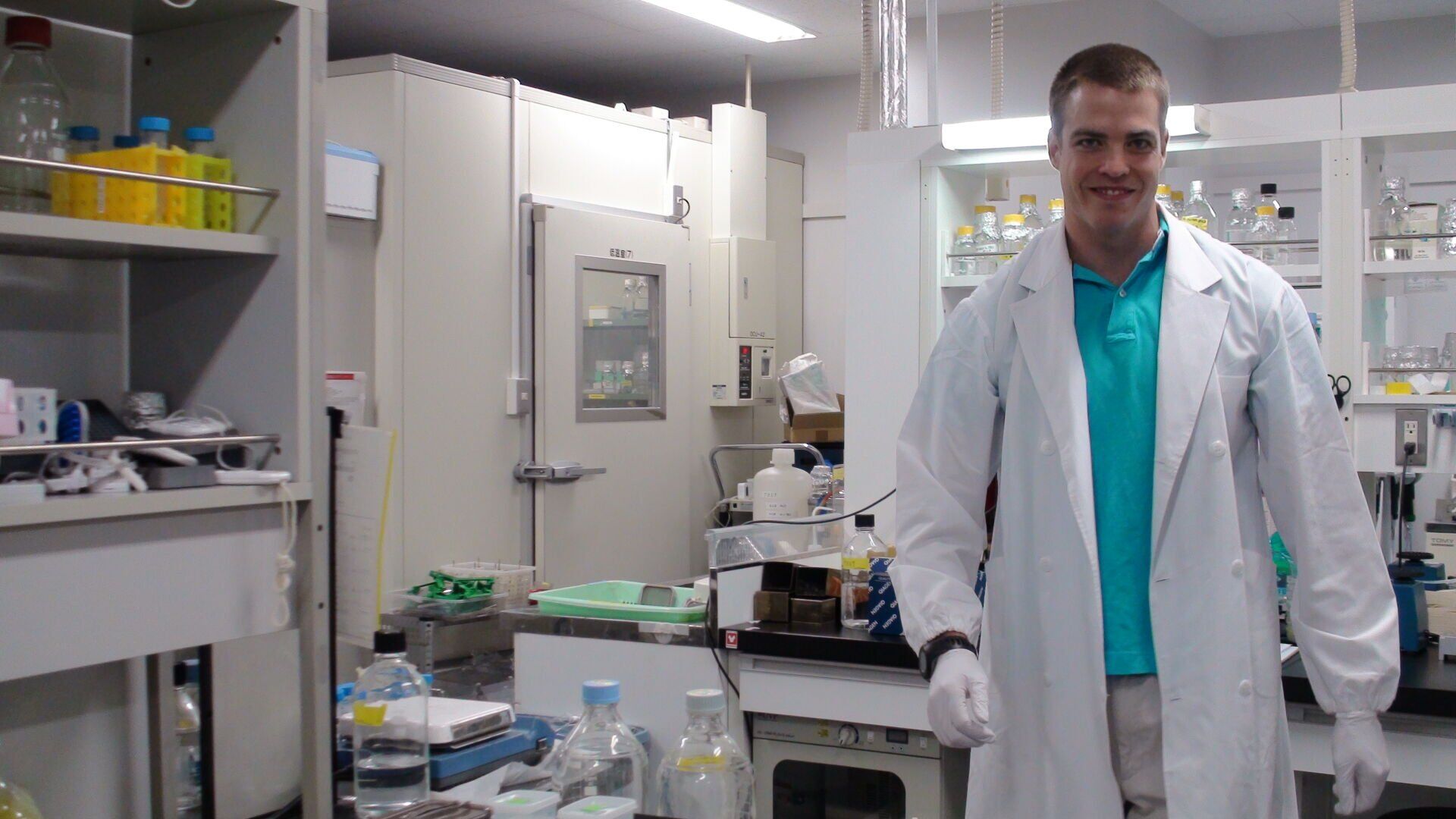

Dr. Tyler LeBaron smiles for the camera at one of the laboratories at Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan, date not specified.

“If we go back to our elementary school, we’ll remember that hydrogen is the first on the periodic table of elements, right?” LeBaron said. “Hydrogen is number one, and that hydrogen doesn’t like to be alone, because it’s actually just one electron and one proton, and so it’s not stable. It’s going to combine with pretty much anything else. It’ll also combine with, like oxygen, to form water. That’s why water is H2O.”

LeBaron said hydrogen can create a hydrogen molecule by combining with another hydrogen atom to form H2. This is called molecular hydrogen, a tasteless, odorless, but highly flammable gas.

LeBaron said that’s only the beginning, as the concentration used in molecular hydrogen therapy isn’t high enough to be flammable, and the molecule has some potentially beneficial effects for the medical field. It’s also natural to the human body.

Dr. Tyler LeBaron performs a test on rat, date and location not specified.

“When we have a healthy microbiome, and we have a healthy diet with fibers in our bacteria, some of our bacteria will actually metabolize those fibers to produce hydrogen gas,” LeBaron said. “So, we’re always exposed to hydrogen gas from really the beginning of life. It’s actually a pretty cool story when you think about hydrogen in general, because hydrogen is the ancestor of all the elements, right?”

Hydrogen has been used to prevent decompression sickness in deep-sea diving since the 1940s, LeBaron said. The therapy could lessen the effects of conditions in the mental space, such as brain damage from a stroke. This was shown in a 2007 Nature Medicine article through tests conducted on rats.

Thus, the purpose of this collaborative study was born, according to a press release.

“The mechanisms underlying the biomedical effects of molecular hydrogen (H2) remain poorly understood and are often attributed to its selective reduction of hydroxyl radicals, based on the long-held notion that H2 is biologically inert,” the press release states.

The doctors involved in this study, including LeBaron, who’s also with the Molecular Hydrogen Institute, moved to explore this matter further and declared that hydrogen molecules are, in fact, not inert, and that they specifically target the Rieske iron-sulfur protein.

“This leads to a brief, controlled suppression of Complex III,” LeBaron wrote in an Instagram post. “The cell interprets this as a mild stressor and activates a protective mitochondrial pathway (UPRmt). Over the next several hours, the mitochondria rebuild, strengthen, and increase resilience. This mechanism helps explain many findings across the literature, including hydrogen’s hormetic-like effects, its ability to normalize biological markers in either direction, and why benefits extend beyond the exposure window.”

According to ScienceDirect, “Hormesis is defined as the phenomenon in which low doses of otherwise harmful conditions lead to adaptive responses that enhance the functional ability of organisms.”

Molecular hydrogen therapy is not FDA-approved, as it’s still in the early stages of research, something LeBaron told St. George News several times.

Tyler LeBaron

LeBaron grew up in Lincoln County, Nevada, in a small town called Caliente, surrounded by mountains. While some kids would read fiction and comics to fantasize about what could be, LeBaron said he read encyclopedias to learn about science.

“Even in elementary school, when I learned that, you know, sugar is not the best thing for you, and I was like, ‘OK, well I’ll stop eating that,’” LeBaron said. “And exercise is important, so I’m going to do that. I want to compete, and I was really into performance. Performance and everything, but I’ve always loved the science. My teachers — they’ll remember I was always reading the encyclopedias. I had the encyclopedias on my desk, and just like, reading all of these things and trying to come up with inventions. It was my passion. I loved it.”

After getting into astronomy and quantum physics in middle school, LeBaron said he had a transformative moment in 2009 while attending college, when he first came across alkaline ionized water. He wondered whether the product’s beneficial claims were true.

“There were some scientific papers on this type of water, but they called it electrolyze reduced water, and I remember, I was talking to my professors, because I started at the university, and they were like, ‘Alkaline water is not going to provide you any benefits,’” LeBaron said. “’This is impossible.’ And you know, they were totally right.”

After exploring this topic further with his professors at the time, LeBaron said he came across an article in Nature Medicine on hydrogen gas. His biochemistry professor printed the article, presented it to LeBaron, and said, “You know, I think there might be something here.”

Dr. Tyler LeBaron tells St. George news about his study on molecular hydrogen therapy, St. George, Utah, Dec. 18, 2025.

LeBaron described this experience as a transition that made him want to understand what he called “the god particle.”

“It’s like, everything is hydrogen, the origins of the universe, the genesis of life, the evolution of life,” LeBaron said. “So I’m like, ‘Wow, this is really cool.’ So that really got me excited about it, so I looked at all the publications that were, and as I said, I needed to do some research for my (biochemistry) internship, and a lot of the research was coming out of Japan. So I contacted Nagoya University, which is like the top, prestigious university there in Japan, and I was able to go there and do research in the laboratory and see things for myself.”

In his off time, however, LeBaron prefers being outdoors, competing in events like local foot races and other competitions. LeBaron also founded the Molecular Hydrogen Institute, a nonprofit organization focused on molecular hydrogen research, and works as a part-time adjunct instructor at SUU.

More information about LeBaron and his endeavors can be found on the Molecular Hydrogen Institute’s website.