This post was originally published on here

Trump’s first and second terms have been marked by huge protests, from the 2017 Women’s March to the protests for racial justice after George Floyd’s murder, to this year’s No Kings demonstrations. But how effective is this type of collective action?

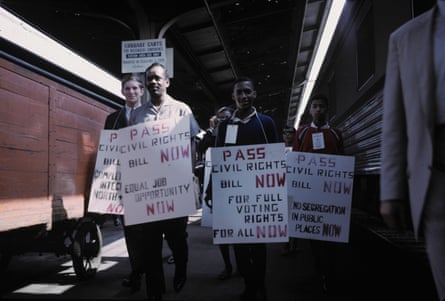

According to historians and political scientists who study protest: very. From emancipation to women’s suffrage, from civil rights to Black Lives Matter, mass movement has shaped the arc of American history. Protest has led to the passage of legislation that gave women the right to vote, banned segregation and legalized same-sex marriage. It has also sparked cultural shifts in how Americans perceive things like bodily autonomy, economic inequality and racial bias.

But as with any tool, there are ways to sharpen and blunt a protest’s impact. Here’s what decades of research tells us about what protest can and can’t do.

Protests can affect elections

When Carmen Perez-Jordan was first asked to organize a national protest for women’s rights, following Donald Trump’s first presidential election win, she did not anticipate that it would become the largest single-day protest in American history. On 21 January 2017, more than 500,000 protesters took to the streets of Washington DC, and as many as 4 million participated in affiliated demonstrations nationwide.

Looking back, Perez-Jordan says the Women’s March engaged millions of people in activism for the first time, inspired other movements like #MeToo and pushed people to see women’s issues beyond reproductive rights. “It was unquestionably impactful,” Perez-Jordan said. “The Women’s March proved that millions will rise up when democracy and human rights are at stake.”

Research confirms that the Women’s March incited tangible change. In particular, it directly prompted an unprecedented surge in female candidates for elected office, which scholars attribute to feeling empowered to draw attention to issues that have historically been dismissed. During the 2018 midterms, more than 500 women ran in congressional races, nearly doubling numbers from 2016.

The protest also changed electoral results. According to one study, regions in which protests had higher turnouts saw positive shifts in votes for Democratic candidates at the county level. Another showed that voters were more likely to support women and candidates of color due to the empowering effect of the protest.

And it isn’t only on the left that this trend can be seen. By the same token, localities that saw greater participation during the 2009 Tea Party protests also witnessed more Republican support during the 2010 midterms, one study finds. This shows the outsize impact a single protester can have, the study’s authors say. That’s because having one more attender at a demonstration rallies more support for a political cause than acquiring one more vote during an election does.

According to the often-cited 3.5% rule, if 3.5% of a population protests against a regime, the regime will fail. Developed by political scientists Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan, who researched civil resistance campaigns from 1900 to 2006, the rule has seen renewed interest in leftist circles recently, especially with No Kings protests attracting historic numbers.

“I understand why people are drawn to it,” Chenoweth said on an episode of the podcast You Are Not So Smart earlier this year. “It looks like a magic number, looks like a number that provides people with certainty and guarantee. And it’s also a surprisingly modest number.”

According to Chenoweth, the number refers to peak, not cumulative participation. She also says 3.5% is not absolute – even non-violent campaigns can succeed with less participation, according to her 2020 update to the rule.

Protests foster lifelong civic engagement

Momentum begins with a first protest, research shows. Citizens who participate in one demonstration are more likely to take part in another.

For example, protesters who took part in the 1964 Freedom Summer – a movement to register Black voters in Mississippi during the civil rights movement – were more likely to engage in activism over the course of their lifespans than those who intended to join the protest, but ultimately did not.

“It tells us that the impact of protesting is more about action than intent,” said Jeremy Pressman, professor of political science at the University of Connecticut. “There is something about being in it that teaches you a certain skillset and makes you feel comfortable in that setting.”

For that reason, protests can build coalitions and networks that can be called upon for future fights. Pressman calls this “organizational success” and says it can be measured by growth in an organization’s membership, funding or even media attention. “You could have a policy failure in that they didn’t adopt a law, but that campaign may have led you to double the size of your organization so you’re more prepared and powerful for your next fight,” he said.

This dynamic can be especially critical in smaller towns and close-knit communities, scholars say, where people may fear voicing an opinion that goes against the grain. In a Trump-leaning county, for instance, a person may not feel comfortable vocalizing a position considered progressive, according to Omar Wasow, assistant professor of political science at the University of California, Berkeley. However, if that same individual sees an anti-Trump protest, they might feel encouraged by the thought that they have neighbors who see things the way they do. “That allows me to know I’m not alone,” he said.

Nonviolence is key

One protesting strategy has been shown time and again to be most effective in the US: nonviolence.

The seminal example of this is the civil rights movement, said Robb Willer, professor of sociology at Stanford University. From refusing to board buses during the Montgomery bus boycott, to refusing to leave a white-only lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, to marching in towns and cities across the nation, civil rights activists showed “extreme discipline” when it came to maintaining nonviolent tactics, he said.

Together, these protesting strategies work towards creating a sympathetic movement that is more likely to sway public opinion, research shows.

In the context of civil rights, the movement’s ability to elicit violence from its opponents – such as in 1965, when armed police violently attacked peaceful protesters crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama – only strengthened public support for the cause. “When the state is perceived as engaging in excess use of force, that tends to generate very sympathetic coverage, and that drives concern,” explained Wasow.

In the same way, protests that engage in violent tactics tend to lose the support of the public, even if it’s only a minority who are involved in the disturbances, and even when a cause is otherwise viewed favorably. Such was the case with the anti-racist counter-protests that unfolded in response to the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. Although it was a white nationalist protester who plowed through a crowd and killed one woman, footage of counter-protesters throwing objects and brawling in the streets lowered their public esteem.

Other tactics that aren’t necessarily violent, but that are destructive nonetheless – like property destruction, setting fires or shutting down interstate highways – can have a similar effect, Willer explained. “People react very negatively to protest tactics that they view as risking harm to people,” he said.

Protests help people feel more effective and hopeful in their own lives

While legislative shifts and movement-building are important markers of impact, another way to gauge success is by considering how a demonstration affects the lives of its participants. In that sense, Pressman says, “it’s important to broaden the menu of what success and failure look like” by gauging success beyond legislation.

For one thing, protesting can improve emotional wellbeing.

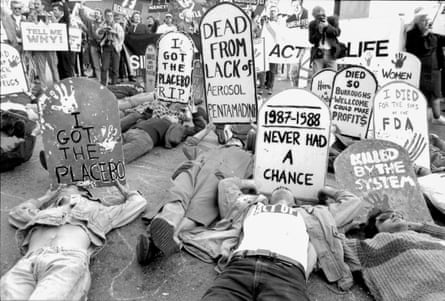

Research shows, for example, that people who were part of the Act Up movement to raise awareness of and demand research into HIV-Aids in the 1980s and 90s continued to feel validated years later having participated in such an impactful movement. “It reshaped the kind of identity and emotional context in which some of the protesters were protesting,” said Pressman.

But shifting to that framework requires thinking less about how protests might shape political strategy and greater focus on whether a movement’s participants feel effective, hopeful and like they are part of a larger community. Said Wasow: “It is important not to get so focussed on big-picture consequences that we lose sight of protest as a way to hold on to one’s agency.”

This is also key since protests rarely incite policy or cultural changes overnight. Often, their rates of impact are much more gradual. For that reason, looking at them through a historical lens – when movements can be digested in terms of years, or even decades – is a helpful way to appreciate the tangible effect of taking to the streets.

“Protests often have a subtle cascade effect,” said Wasow. “These are long-term fights.”