This post was originally published on here

A University of Arizona-led study published this month in Science Advances documents more than 16,000 new species described annually from 2015 to 2020, with 17,044 in 2020 marking the highest rate in history. Researchers analyzed taxonomic histories of approximately 2 million known species and found discovery rates climbing rather than plateauing.

The study challenges assumptions that the golden age of species discovery has ended. Lead researchers examined records across all groups of living organisms to track patterns over time. Their analysis revealed consistent increases in annual descriptions, countering claims of a slowdown.

Some scientists have suggested that the pace of new species descriptions has slowed down and that this indicates we are running out of new species to discover, but our results show the opposite,

said John Wiens, professor in the University of Arizona Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and senior author. In fact, we’re finding new species at a faster rate than ever before.

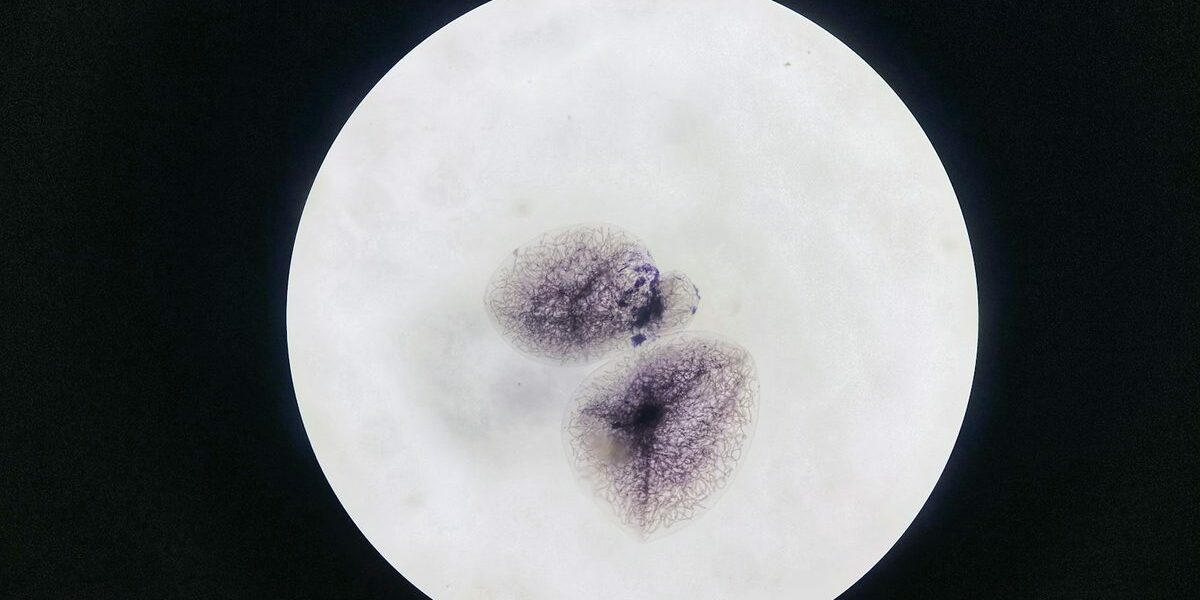

Recent annual discoveries include more than 10,000 animals, primarily arthropods and insects. Plant descriptions average approximately 2,500 per year, while fungi account for about 2,000. These figures reflect detailed taxonomic work on major biological kingdoms.

Projections from the study indicate Earth’s biodiversity surpasses current tallies. Fish species may total 115,000, compared to 42,000 described. Amphibians could number 41,000, against 9,000 documented. Plants might exceed half a million species.

New species descriptions outpace extinctions. Wiens estimated extinctions at roughly 10 species per year in a separate October study. Fifteen percent of all known species were discovered in the past 20 years alone.

Most new species currently receive identification through visible traits. Wiens noted advances in molecular tools will detect additional cryptic species, defined by genetic differences undetectable by appearance alone. Right now, most new species are identified by visible traits,

Wiens said. But as molecular tools improve, we will uncover even more cryptic species—organisms distinguishable only on a genetic level.

Scientific description and formal naming precede any protection for species. This documentation serves as the initial requirement for conservation measures to prevent extinctions.

Newly discovered organisms provide medical and technological applications. GLP-1 receptor agonists, used in weight-loss drugs, derive from a hormone in Gila monsters. Spider and snake venoms, plus compounds from plants and fungi, offer prospects for pain and cancer treatments.

Researchers intend to identify geographic hotspots concentrating undiscovered species. They also plan to assess shifts in the field, from dominance by European scientists to documentation by researchers in species’ native countries. So much remains unknown, and each new discovery brings us closer to understanding and protecting the incredible biodiversity of life on our planet,

Wiens said.