This post was originally published on here

The science here might be hard to follow for non-scientists at times, but it’s worth it, as it will reward those who are willing to work a little to understand how atomic energy, electricity and radiation were discovered and developed.

The book is full of insights into how huge scientific discovery stories develop, slowly, step by step, with an occasional sprinkling of insight, or good fortune.

This author describes how, in the real world of science, collaboration and persistence are most often what drive things relentlessly forward, rather than the public’s image of a singular genius working alone, having Eureka moments.

There are stories that bring the personalities of the gifted scientists who drove the birth of the atomic age to life, including New Zealander Ernest Rutherford, a scientific giant who led Cambridge’s Cavendish lab at the epicentre of it all.

Rutherford was a notoriously demanding boss, big physically and not easily ruffled. He was awestruck, though, when he discovered the atomic nucleus by firing powerful alpha particles at gold and seeing some particles bounce back.

The author reports that Rutherford said: “It was as though you had fired a 15-inch shell at a piece of tissue paper and it had bounced back and hit you.”

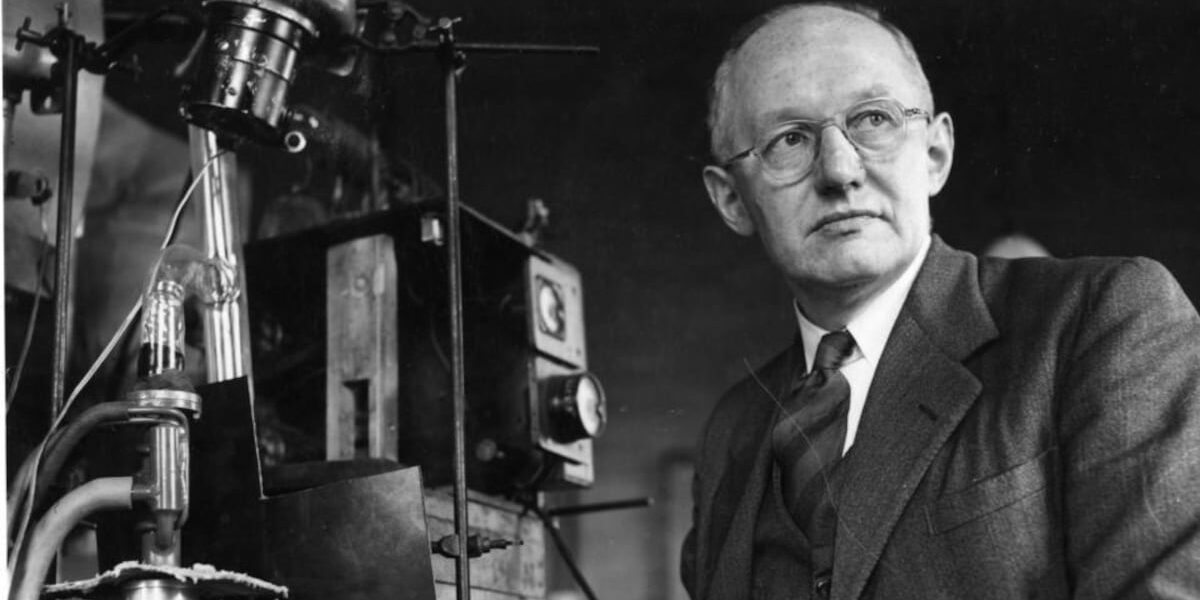

All the stages on the path to Hiroshima and Nagasaki are dealt with, including the splitting of the atom in 1932. That effort was led by Rutherford, working with Ireland’s Ernest Walton – an experimentalist – and the theorist John Cockcroft.

Nuclear physics, the author says, was born in 1933 at the Solvay Conference in Brussels when the parts of the atom – proton, electron, neutron – were agreed.

After that the race began to develop the atomic-bomb, with allied urgency fuelled by real fears that Nazi Germany had the scientists to get there first.

The allies won the race with the help of talented Jewish scientists who fled Germany and Italy, like Albert Einstein, Enrico Fermi and Edward Teller.

When Hitler was defeated, new battle lines were drawn, with the US and the USSR developing hydrogen bombs 3,000 times more powerful than Hiroshima.

This horrified many of the scientists involved in the birth of the atomic age, including Ernest Walton, who joined Pugwash, a still active international organisation, founded in 1957 with the aim of abolishing nuclear weapons.