This post was originally published on here

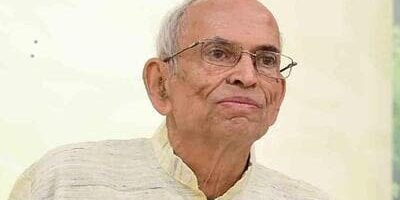

Pune: Veteran ecologist Madhav Gadgil has consistently argued that environmental conservation in India must place human life and livelihoods at its core, especially those of forest-dependent and marginalised communities. A strong advocate of biodiversity protection, Gadgil has opposed rigid, protectionist conservation models that, he says, elevate animal rights above human survival and dignity.

Best known for heading the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel, Gadgil has for decades pushed for a democratic, decentralised and community-led approach to wildlife governance. Over the past two years, he has repeatedly sought permission for regulated hunting in areas facing excessive wild animal populations, including parts of Pune district where leopard numbers have risen sharply.

In an interview with HT in November 2025, Gadgil explained the reasoning behind his demand, stressing the need to empower local communities to deal with human-wildlife conflict.

“If a human enters your home and attacks you, you have the right to defend yourself—even if that means killing the intruder. So why does that right disappear when the attacker is a wild animal?” Gadgil said. “This is the fundamental contradiction people living in conflict zones face every day. Their safety is treated as secondary.”

He has been particularly critical of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, arguing that its implementation often places species such as leopards and wild boars “above human lives”—a position he has described as “completely absurd” in conflict-prone landscapes.

Drawing international comparisons, Gadgil has frequently cited Scandinavian countries as examples of pragmatic wildlife management. “Scandinavia faced severe conflict due to rising wolf populations. They believe wildlife is a renewable resource,” he said. “When animal populations exceed ecological or social carrying capacity, they are harvested in the interest of long-term balance. Decisions are taken locally on how much population can be sustained.”

He pointed to Sweden’s management of its large reindeer population, where decentralised decision-making and regulated hunting have helped prevent human–wildlife conflict. “They don’t wait for tragedies. They prevent them,” Gadgil said.

Equally central to Gadgil’s work has been his advocacy for the rights of tribal and marginalised communities. He has repeatedly emphasised that communities traditionally dependent on forests—who have also played a key role in conserving them—should not be stripped of their rights in the name of conservation.

Another defining aspect of Gadgil’s legacy is his commitment to taking science beyond elite academic spaces. Among the few Indian scientists to consistently communicate in local languages, he wrote extensively in Marathi and supported translations into other regional languages. He believed scientific knowledge should be accessible to ordinary citizens rather than confined to English-speaking circles.

Through newspaper columns, popular science writing and public lectures, Gadgil explained complex ecological ideas in simple, relatable terms, often drawing on folk knowledge, local practices and everyday observations of nature.

Amit Wadekar, secretary, Pune-based Vanrai organisation, said Gadgil firmly believed science communication must happen in local languages. “He wrote several books and articles in Marathi and ensured his work was translated into other regional languages. He also stressed that ecological knowledge available in local languages should be preserved,” Wadekar said.