This post was originally published on here

As the UK continues to battle snow and icy conditions this week, scientists have warned that British winters could get even worse.

Although climate change is making the planet warmer, experts say it could destabilise key weather patterns that currently protect the UK from freezing extremes.

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is the massive ocean current that powers the Gulf Stream, driving warm tropical waters northwards to the UK.

If this key current were to collapse, climate scientists predict that London could see winter extremes of -20°C (-4°F), with three months of the year spent below freezing.

Likewise, temperatures in Edinburgh could fall to one-in-ten-year extremes of -30°C (-22°F) as Scotland faces five and a half frozen months each year.

Concerningly, these extremes are no longer an entirely remote possibility, as scientists warn that the imminent collapse of AMOC is increasingly likely.

Professor Tim Lenton, a leading climate scientist from Exeter University, told the Daily Mail: ‘The probability of AMOC collapse is already non-zero, and it increases with global warming.

‘At 2°C of global warming, the odds of AMOC collapse are comparable to Russian Roulette – a one in six chance of a highly damaging outcome.’

Why would British winters get colder?

While it might not feel like it at the moment, British winters are currently warmer than they might otherwise be thanks to the continual motion of the AMOC.

Described as ‘the conveyor belt of the ocean’, AMOC transports warm water near the ocean’s surface northwards from the tropics up to the northern hemisphere.

Heat released from the ocean contributes to helping UK winters remain relatively warm and stable.

However, experts are now concerned that the engine driving this global conveyor belt is starting to falter.

As warm water moves northwards towards Greenland, it freezes into sea ice and leaves salt behind in the ocean.

This creates extremely cold, dense, salty water that falls to great depths, around 1,000 to 4,000 metres below the surface, and is carried southward.

Dr René van Westen, of Utrecht University, told the Daily Mail: ‘This sinking process is crucial for having a strong and stable AMOC.’

However, the ongoing warming of the North Atlantic and Arctic oceans is now preventing the water from cooling and becoming denser.

At the same time, increased runoff from melting ice caps is adding fresh water to the oceans, preventing the water from becoming salty enough.

‘The surface water masses are now getting lighter under climate change, meaning that less sinking takes place and this results in AMOC weakening or even collapse,’ says Dr van Westen.

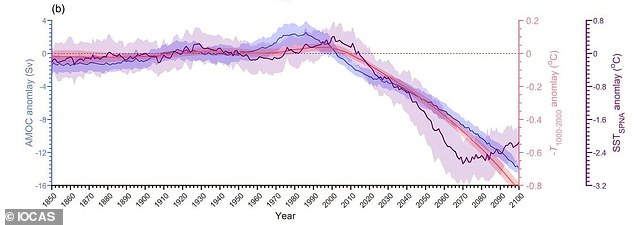

Scientists have already observed that AMOC has slowed due to human-caused changes in the climate, but there are now concerns that it could be driven into total collapse.

If this were to happen, the UK would no longer benefit from the warming effects of tropical waters.

This would mean that winters would get colder, even as climate change increased the average temperature of the planet.

Professor David Thornalley, an ocean and climate scientist from University College London, told the Daily Mail: ‘If the AMOC weakens by enough, then the regional cooling caused by the weaker AMOC can more than counteract the regional warming effect expected from the effects of higher greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere.’

‘Under cases of an AMOC collapse, some results suggest UK winters would be up to 15°C (27°F) cooler.’

It might take decades for the effects of a collapse to be felt, but some changes may be apparent within a single lifetime.

According to one climate model, the UK would be 6°C (10.8°F) colder by 2050 if the AMOC collapse took place in 2030.

Meanwhile summer rainfall would plummet by up to 35 per cent, increasing the risk of drought, and winter rainfall would increase by 20 per cent over the north of the UK.

However, other models predict even more extreme weather conditions across northern Europe.

In a recent study, Dr van Westen and his co-authors predicted that a northern city like Edinburgh would face 164 days with minimum temperatures below freezing, that’s almost 50 per cent of the year, and an increase of 133 days compared to the pre-industrial climate.

In Scandinavia, even Norway’s typically mild west coast could experience winter extremes below -40°C (-40°F), that is 25°C (45°F) colder than in the pre-industrial climate.

In this scenario, expanding sea ice could cover parts of the British Isles, and there would also be increased winter storms.

How likely is an AMOC collapse?

The question of whether AMOC is on track to collapse is hotly contested in climate science, and not one to which there is a definitive answer.

However, there is a significant body of research that shows the risks of AMOC collapsing increases with climate change.

Two recent studies published by British and Dutch researchers suggest that there is a greater than 50 per cent chance of AMOC collapse in intermediate climate warming scenarios and that the current may start to collapse around 2060.

Some models and researchers give lower values for this risk or downplay the risk of collapse entirely.

But a bigger concern for some researchers is that there might be hidden risks of collapse in the future that current climate models don’t pick up.

Professor Thornalley says: ‘There is quite a lot of uncertainty about whether there may be a feedback that kicks in, such that once a weakening starts, it causes further weakening and the AMOC goes on to collapse. This is what is called a tipping point.’

‘New work has suggested that the chance of a collapse is greater than previously thought, simply because we hadn’t examined the results of climate model simulations beyond 2100.

‘It turns out that although most climate models don’t have an AMOC collapse by 2100, many do go on to collapse in the 22nd century, and it is found that the tipping point – the point of no return – was often reached early in the 21st century.’

That means humans might be driving the planet towards future environmental collapse without realising how imminent the effects could be.

Experts said the likelihood of AMOC collapsing is strongly dependent on how humans act to bring climate change under control in the next few years.

If humans burn more fossils than currently predicted, then the current best estimate is that the chance of an AMOC collapse might be as high as 70 per cent.

Whereas, if the world sticks to or improves on the current target to reduce fossil fuel burning, the odds of total collapse drop to around 25 per cent.

If AMOC only weakens, any cooling will likely be cancelled out by the warming effects of climate change, so winter will have roughly the same average temperatures.

However, the weakening of AMOC would be a major change in how heat is circulated around the globe, which would have catastrophic effects on seasonal weather patterns.

Professor Thornalley says: ‘There will be very strong temperature gradients in our region, which will cause more extreme and violent weather.

‘The lesson is that we really want to avoid causing any large changes in the AMOC since it will disrupt our climate in a way that has bad impacts on our society and economy.’