This post was originally published on here

Palpu Pushpangadan and his colleague S. Rajasekharan entered the forests of the Agastya hills in Thiruvananthapuram in 1987 as ethnobiologists, tasked with documenting the region’s rich biodiversity under the All India Coordinated Research Project on Ethnobiology (AICRPE). Within the first few days of fieldwork, an apparently simple observation proved transformative. While the scientists were visibly tired after long treks through the forest, the Kani tribal youth accompanying them as guides showed no signs of fatigue. When he asked the Kani boys about it, Pushpangadan learned that they were chewing the fruits of a forest plant to sustain energy and vitality. After some persuasion—reflecting both the guarded nature of indigenous knowledge and the trust slowly built through engagement—the Kani agreed to share details about the plant. Pushpangadan and the team consumed the berries and experienced a sense of rejuvenation. The plant, known to the Kani as ‘Arogyapachcha (the source of evergreen health)’, was botanically identified as Trichopus zeylanicus travancoricus.

The beginning

This encounter marked the beginning of one of the most consequential stories in modern ethnobiology. Samples of the fruit and other plant parts were taken for phytochemical and pharmacological analysis to the Regional Research Laboratory (RRL), Jammu, which coordinated the AICRPE, under the leadership of Pushpangadan. Investigations revealed the presence of glycolipids and non-steroidal polysaccharides with immuno-enhancing and anti-fatigue properties, overturning initial expectations of steroidal compounds. Detailed scientific validation followed, leading to patent filings and establishing the plant’s significance well beyond its local context. What began as a field observation thus evolved into a bridge between indigenous knowledge and modern science.

Interdisciplinary demands

In 1990, Pushpangadan, then chief coordinator of AICRPE, moved from RRL Jammu to become Director of the Tropical Botanic Garden and Research Institute (TBGRI) in Thiruvananthapuram. The research on arogyapachcha moved with him, entering a new institutional phase. Recognising the interdisciplinary demands of drug development, Pushpangadan constituted a diverse research team drawing on pharmacology, phytochemistry, biochemistry, and Ayurveda, fields that were not fully integrated within TBGRI then. Importantly, as the research progressed, two of the original Kani guides were formally included as consultants and paid a consolidated monthly fee between 1993 and 1998. This step, modest as it may appear in retrospect, was symbolically significant: it acknowledged indigenous contributors as participants in the research process rather than invisible informants.

By 1994, the work culminated in the development of Jeevani, a polyherbal formulation intended as a health-promoting tonic. Notably, while the Kani traditionally used only the fruits of arogyapachcha, Jeevani was developed from the plant’s leaves—never used by the community—and these constituted only about 13–15 per cent of the final formulation. The remainder drew upon broader Ayurvedic knowledge systems. This distinction later assumed importance in debates on intellectual property, consent, and the nature of contributions to traditional knowledge.

Transfer of technology

In November 1996, TBGRI transferred the technology for manufacturing Jeevani to Arya Vaidya Pharmacy, Coimbatore, for a licence fee of ₹10 lakh (approximately U.S. $25,000 at the time) and a royalty of 2% on ex-factory sales. Crucially, Pushpangadan proposed and successfully institutionalised a benefit-sharing arrangement whereby the licence fee and royalties would be divided equally between TBGRI and the Kani community. To manage these funds, the Kerala Kani Samudaya Kshema Trust was registered in November 1997. Although concerns were initially raised regarding its representativeness and long-term viability, the trust became an enduring institutional mechanism for channelling benefits to the community.

The ethical and political significance of this arrangement extended far beyond Kerala. The Kani case unfolded against the backdrop of the emerging global biodiversity regime. The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), adopted at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992 and entering into force in 1993, sought to correct historical inequities in the use of biological resources. For countries of the Global South, the CBD represented a response to decades of biopiracy, asserting national sovereignty over genetic resources and emphasising prior informed consent and fair and equitable sharing of benefits. Yet the CBD articulated principles rather than detailed mechanisms. How, in practice, could benefits be shared?

Who represented communities? How could traditional knowledge be recognised without being reduced to commodities?

It was here that Pushpangadan emerged as a pivotal figure. Long before national legislation such as the Biological Diversity Act, 2002, or international instruments such as the Bonn Guidelines and the Nagoya Protocol, the Kani–TBGRI arrangement provided a real-world experiment in Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS). The case became a key reference point in debates on the relationship between the CBD and the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Agreement, particularly for developing countries, arguing that ABS was both feasible and necessary. While many industrialised countries dismissed ABS as impractical or insisted it remain a purely national concern, the Kani experience demonstrated that structured benefit sharing, though complex and imperfect, could be implemented.

Norm entrepreneurship

Pushpangadan’s contribution thus lay not only in scientific discovery but in norm entrepreneurship. By translating ethical commitments into institutional arrangements, he helped shape the global discourse on indigenous knowledge and intellectual property from the perspective of the Global South. The Kani case revealed tensions within communities, between conservation and commercialisation, and between customary knowledge systems and patent regimes, but it also provided lessons that informed subsequent policy evolution.

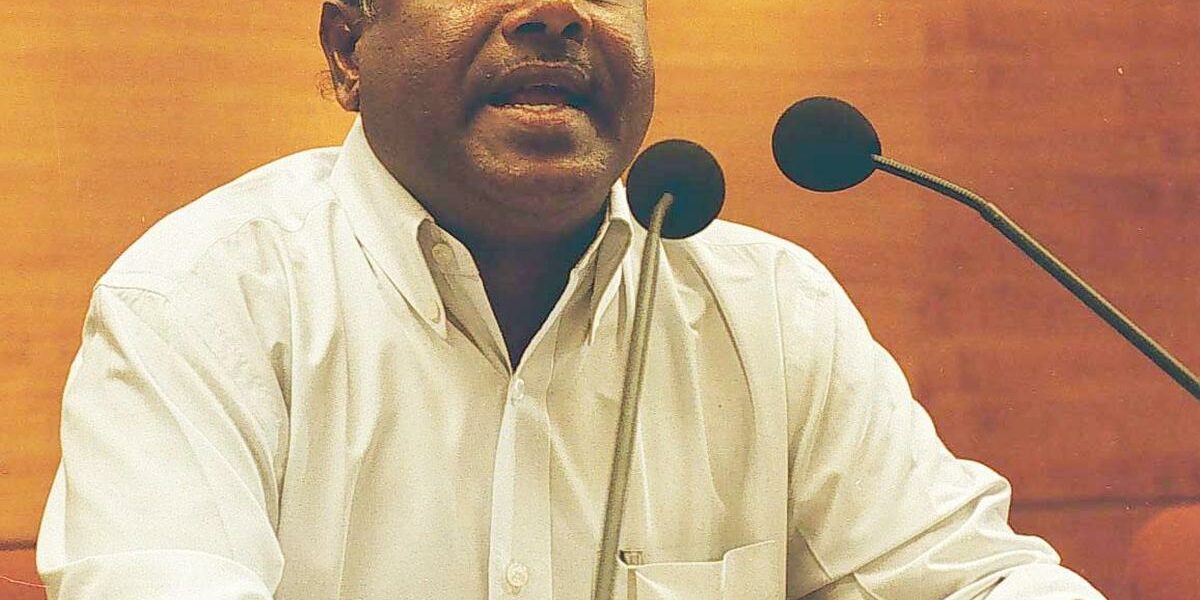

Palpu Pushpangadan is remembered today as an eminent ethnobotanist and institution-builder, but his deeper legacy lies in having foregrounded equity within biodiversity science. From a moment of shared berries in the Agastya hills emerged a global conversation on justice, knowledge, and stewardship. His life’s work reminds us that sustainable futures depend not only on conserving biodiversity, but on recognising and respecting those who have long lived with it as knowledge holders, custodians, and partners.

(Sachin Chaturvedi is Vice Chancellor, Nalanda University. The views expressed are personal)

Published – January 11, 2026 01:22 am IST

Email

SEE ALL

Remove