This post was originally published on here

A team of researchers at Stanford University has developed a novel technique that reveals these microscopic structures with unprecedented clarity, using only a rotating light source and a camera-equipped microscope.

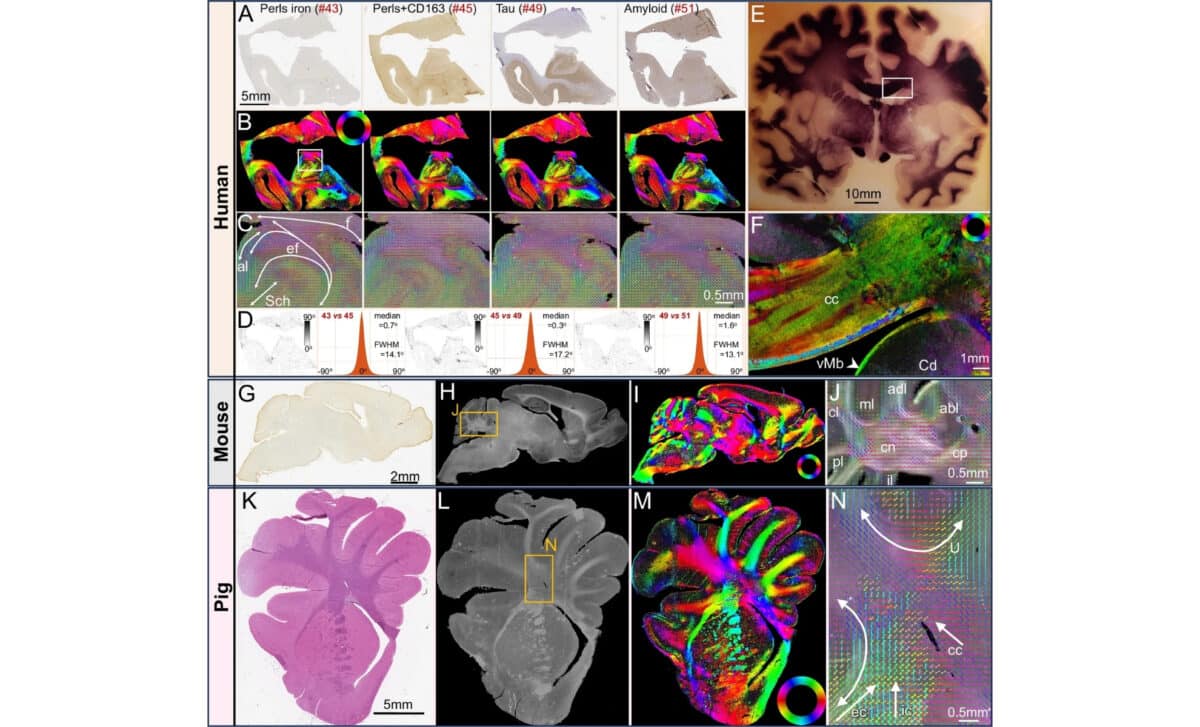

These fibers are embedded in virtually every tissue in the human body, playing essential roles in everything from muscle function to brain communication. Their deterioration has been linked to major diseases, including neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s. Despite their importance, studying them has been a major technical hurdle, until now.

A Rotating Light, a Game-Changing View

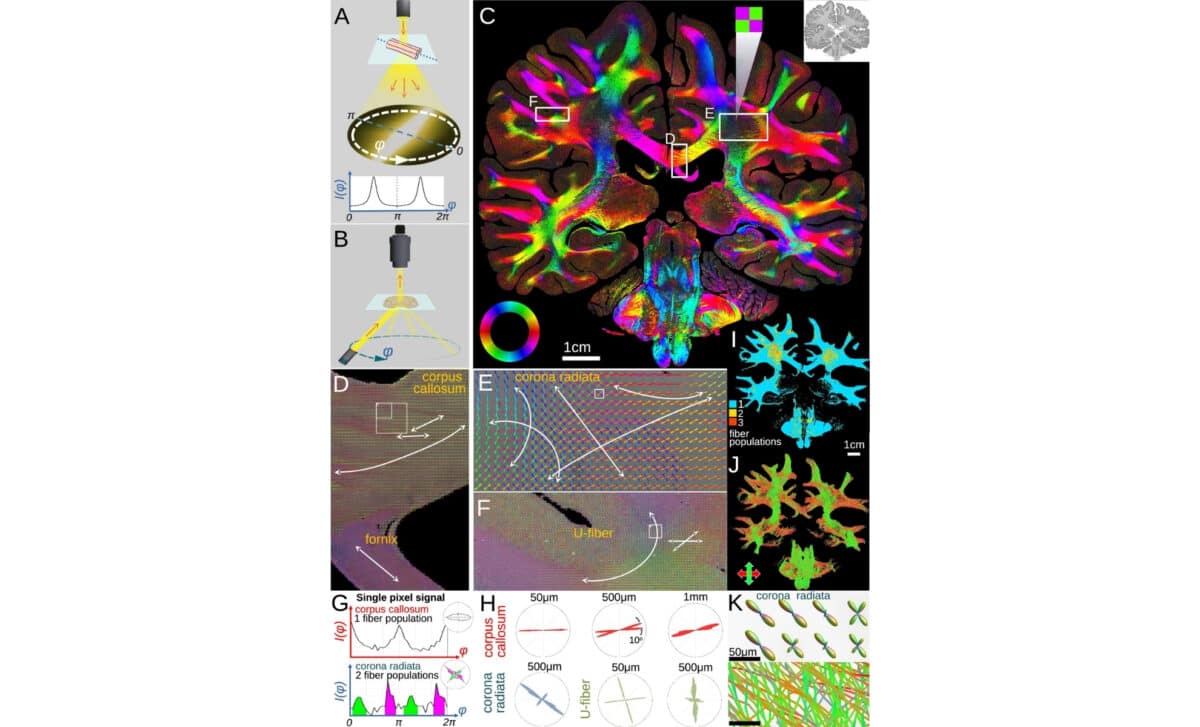

The new imaging method, dubbed computational scattered light imaging or ComSLI, allows scientists to detect fiber orientations inside tissues by analyzing how light scatters when it hits microscopic structures from various angles.

Unlike previous systems that required staining or expensive tools, ComSLI operates with simple components and works on standard tissue slides. According to Popular Mechanics, the only equipment needed is “a rotating LED light source and a microscope camera,” meaning laboratories around the world can adopt it without significant investment.

Researchers can now create detailed, color-coded maps known as “microstructure-informed fiber orientation distributions.” These maps reveal the layout of fibers with micrometer precision, even in samples that are decades old. In other words, the past is suddenly accessible in ways never imagined before.

Mapping Disease in Unseen Layers

Using this new lens, the team at Stanford examined brain tissue from Alzheimer’s patients and noticed stark changes in the hippocampus, a region crucial for memory. The high-resolution images showed “striking microstructural deterioration,” with fewer fiber crossings than those seen in healthy brains. The technique also successfully rendered fine details in muscle, bone, and vascular tissues.

“This is a tool that any lab can use,” said Michael Zeineh, a co-author of the study, in a university press statement. The accessibility of the method means labs can revisit old slides and discover what had previously gone unnoticed, opening the door to fresh diagnostics and research. According to Zeineh, one of the most promising aspects of ComSLI is that it requires no “specialized preparation or expensive equipment.”

Rediscovering What’s Been Forgotten

Perhaps the most surprising potential lies in applying this tool to historic samples. Because ComSLI doesn’t depend on chemically altered slides, it can be used on archival specimens stored for decades—or longer. “Another exciting plan is to go back to well-characterized brain archives or brain sections of famous people,” said Marios Georgiadis, the lead author of the study, in the same release, “and recover this micro-connectivity information, revealing ‘secrets’ that have been considered long lost.”

By re-examining old slides through this modern lens, scientists could shed new light on how conditions progressed in the past, helping clarify patterns of disease and health. The approach may transform how medical archives are used, not just as records, but as living tools for discovery.