This post was originally published on here

A team of scientists has captured and analyzed ancient air trapped in rocks for over 1.4 billion years, revealing surprising details about Earth’s early atmosphere. The study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), opens a new window into a time long before complex life emerged, offering clues about how the planet’s climate and biosphere evolved.

Breathing the Past: Sampling Billion-Year-Old Air

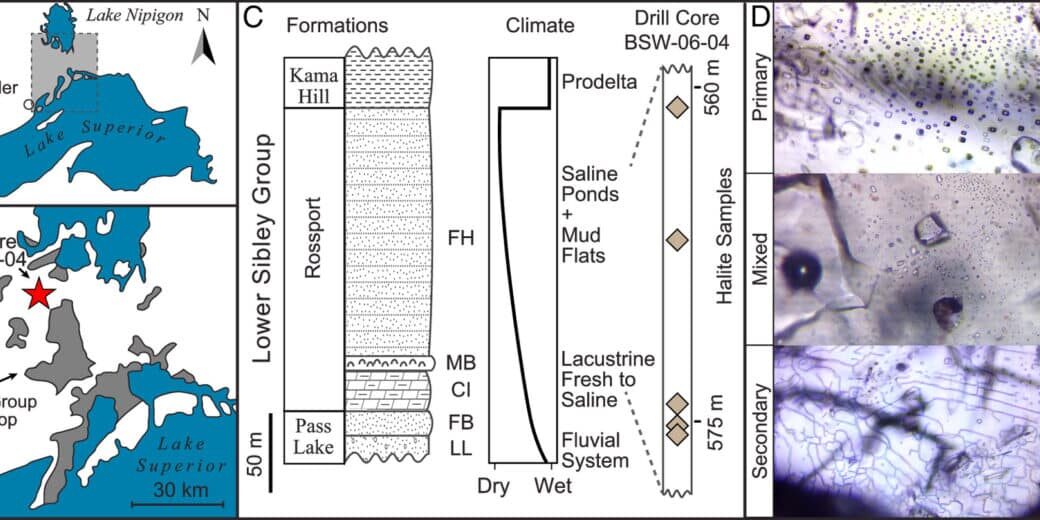

In a groundbreaking study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), and conducted by researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) and their collaborators, scientists successfully extracted tiny air bubbles sealed inside salt crystals dating back 1.4 billion years. This allowed them to directly measure the composition of Earth’s ancient atmosphere, a feat once thought impossible.

“The carbon dioxide measurements Justin obtained have never been done before,” said RPI’s Morgan Schaller, co-author of the study, praising lead researcher Justin Park, a graduate student at the institute. “We’ve never been able to peer back into this era of the Earth’s history with this degree of accuracy. These are actual samples of ancient air!”

The data showed that carbon dioxide levels were dramatically lower than previously estimated for that time period. This challenges long-standing models that suggested the planet’s early atmosphere was rich in greenhouse gases to compensate for the faint young Sun. The results suggest Earth may have maintained a delicate thermal balance far earlier than believed, perhaps aided by a stable, oxygen-poor but methane-influenced climate system.

A Planet Before Complex Life

The study’s findings have profound implications for how scientists understand the conditions that preceded the rise of multicellular organisms. “Despite its name, having direct observational data from this period is incredibly important because it helps us better understand how complex life arose on the planet, and how our atmosphere came to be what it is today,” Park said.

At the time the air was trapped, Earth was dominated by microbes, with little oxygen and no plants or animals. The atmosphere was likely tinted orange or pink due to methane haze, resembling that of Saturn’s moon Titan. Until now, researchers could only rely on indirect geochemical clues to estimate the composition of the air, a method full of uncertainty. But this direct sample provides a rare “snapshot” of the Proterozoic atmosphere, offering new constraints on how life and climate co-evolved.

The PNAS publication emphasizes that these findings bridge a crucial gap in Earth’s timeline, between the planet’s earliest microbial life and the later explosion of biodiversity known as the Cambrian explosion, about 540 million years ago.

Rewriting the Climate Story of Early Earth

This unexpected discovery forces a reevaluation of long-held assumptions about Earth’s thermal history. If carbon dioxide levels were indeed lower than predicted, it implies the planet’s greenhouse effect was weaker, raising new questions about how it avoided global glaciation under a fainter Sun. Some scientists propose that methane, a potent greenhouse gas released by ancient microbes, may have compensated for the lack of CO₂.

This insight not only reshapes our understanding of Earth’s past but also influences the search for life beyond our planet. If similar atmospheric conditions existed on other worlds, it could mean habitability is possible under a broader range of conditions than we thought. The results could guide how future missions interpret atmospheric signatures on exoplanets orbiting distant stars.

What Ancient Air Tells Us About the Future

While the study focuses on Earth’s deep past, it offers a sobering reflection on the present. The team’s ability to capture ancient atmospheric fingerprints provides a stark contrast to today’s rapidly changing carbon cycle. Modern CO₂ levels now exceed anything seen in hundreds of millions of years, a reminder of how dramatically human activity has altered the planet’s climate trajectory.

By comparing these billion-year-old samples to today’s atmosphere, scientists gain not only context for our origins but also perspective on our responsibility to maintain planetary stability. This is not merely a story about ancient rocks, it’s about how understanding the past could guide us toward a more sustainable future.