This post was originally published on here

Your iPhone‘s battery life might be impressive, but it’s nothing compared to the longevity of these ancient ‘walkie-talkies’.

Prehistoric shell trumpets used to communicate over long distances have played a tune for the first time in over 6,000 years.

Archaeologists tested 12 Neolithic trumpets found in what is now Catalonia, Spain, dating back to between 3650 BC and 4690 BC.

Amazingly, eight of the instruments still worked perfectly, with the loudest toot reaching 111.5 decibels – as loud as a powerful car horn or trombone.

Researchers believe that these trumpets would have been used as an ancient form of communication technology, with simple codes shared between communities.

These blasts could easily travel the three to six miles (five to 10 km) between the Stone Age villages where the horns were discovered.

They could have been used to communicate between different settlements, warning of attacks or coordinating harvest times.

Others, found deep within abandoned mines, might have been used to send messages through the underground darkness.

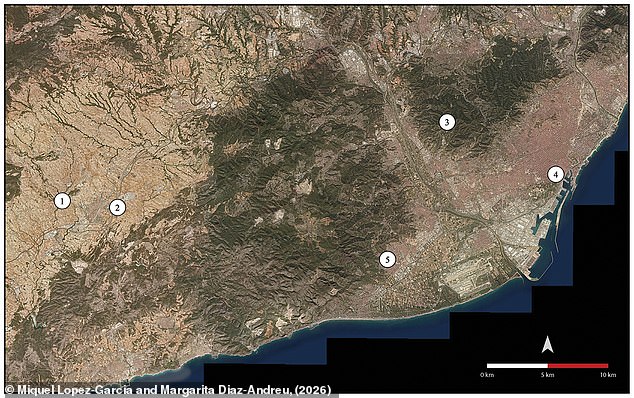

These ancient instruments, analysed in a study published in the journal Antiquity, were found in five archaeological sites clustered in a small region along the Llobregat River in Catalonia.

The closeness of the sites, which were no more than six miles (10 km) apart, suggests that this might have been part of a shared cultural practice.

Two locations were farming communities, located just far enough apart that they would be out of eyesight over flat land.

However, the researchers argue that these shell trumpets were more than loud enough to enable communication between the villages.

During times of harvest or planting, as people spread out into the surrounding fields, this could have allowed for coordination much faster than sending out messengers.

One trumpet came from a cave called Cova de L’Or, high in the mountains, where its blast would have bounced around valleys and peaks far further than anyone could see.

Another seven trumpets were found inside the Neolithic mines of Espalter and Can Tintorer.

During the Stone Age, people used these sites to excavate variscite, a green mineral used in jewellery.

Co-author Dr Margarita Díaz-Andreu, from the University of Barcelona, told the Daily Mail that these might have been used for ‘signalling for dangers in the mine or a form of communication in a dark and very sonorous place’.

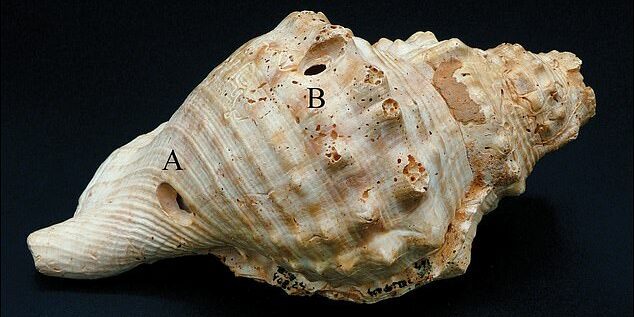

Each trumpet is made from the modified shell of the Charonia sea snail, also known as Triton’s Trumpet, with the tip carefully removed to make a mouthpiece.

The fact that these large shells showed damage from wormholes and sea sponges suggests that they were gathered dead from the sea floor.

This means that Catalonia’s ancient people were specifically gathering the snails for their musical properties, rather than collecting them to eat.

Likewise, the musical properties of the eight functioning horns suggest that extreme care was taken in their construction.

Lead author Dr Miquel López-Garcia, from the University of Barcelona, is not only an archaeologist but also a professional trumpet player – putting him in a unique position to put the horns through their paces.

He found that horns with clean, regular cuts and a 20-millimetre-wide mouthpiece enabled loud, stable notes.

The best trumpets could produce three distinct notes, with an extremely consistent pitch.

The researchers say that this would have allowed for more complex melodic sequences rather than just simple alarms.

Horns with mouthpieces cut wider than this had the potential to make a more powerful sound, but weren’t as consistent in their tone.

Some horns had small holes drilled into them that are likely for attaching a carrying strap, since they didn’t alter the tone when covered or released.

But the bigger mystery may be why this form of communication technology inexplicably vanished around 3600 BC.

The archaeological records suggest that horns were widely used for communication for about 1,500 years.

Horns then disappear from about 3,000 years before reemerging during the Ice Age.

Given that other Mediterranean regions kept using Charonia shells as horns, it must have been something specific that caused Catalonia to give up this useful tool.

However, scientists currently have no idea what this mysterious cause might have been.