This post was originally published on here

Here’s what you’ll learn when you read this study:

- While scientists have a pretty good handle on how protons and neutrons form stable nuclei, there are exceptions to those well-established rules.

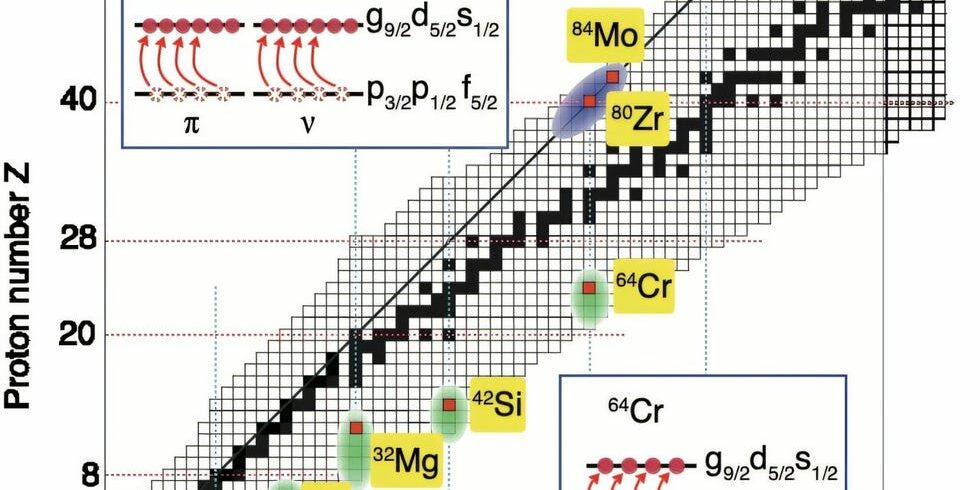

- Known as “Islands of Inversion,” these areas are regions where spherical shapes collapse and deformed objects reign, and typically, they’re found in neutron-rich isotopes.

- A new study found what it calls an “Isospin-Symmetric Island of Inversion” in a stable region on the proton-rich side of the atomic stability line, offering new understanding regarding how atoms form.

In 1911, New Zealand physicist Ernest Rutherford theorized that atoms contained a nucleus, and in the ensuing century, scientists have learned a lot about the ins and outs of that nucleus while filling out the periodic table with 118 atomic elements.

It turns out atomic nuclei follow some simple rules. For example, when it comes to light nuclei (a.k.a. elements with smaller numbers on the periodic table), having the same number of neutrons and protons increases stability and forms what is known as the N=Z line (“N” being neutrons and “Z” being protons). However, as those numbers grow, the repulsive electromagnetic forces in protons require the presence of an increasing number of neutrons for stability (if there aren’t enough neutrons, the protons will repel each other and push the nucleus apart), resulting in a deviation from this line.

That said, over the years, scientists have also noticed a few behavioral quirks known as “islands of inversion,” where the usual rules of nuclear structure stop working. In other words, “magic numbers”—the counts of protons and neutrons that form stable nuclei—disappear, giving way to unusually strong deformations (how much the shape of the nucleus varies from spherical).

Most of these “islands” occur in exotic isotopes like beryllium-12, magnesium-32, and chromium-64, which are all pretty distant from ‘normal’ nuclei found in nature and are on the neutron-rich side of the stability line. For instance, the most common isotope of chromium is chromium-52, which contains 24 protons and 28 neutrons. Chromium-64, on the other hand, contains 24 protons and a whopping 40 neutrons.

But in a new international study, scientists discovered a remarkably proton-rich island of inversion (with symmetrical proton and neutron excitations) by examining two isotopes of molybdenum: Mo-84 (Z=N=42) and Mo-86 (Z=42, Z=44). They found that the difference of just two neutrons caused Mo-84 to experience what’s called “particle-hole excitation,” where nucleons jump to higher-energy orbitals and leave vacancies in their wake.

Because this behavior occurs in a stable region, where the number of protons approximately equals the number of neutrons, this discovery challenges where certain “islands of inversion” may appear while providing a new look into how nuclei bind together. The results of the study were published in the journal Nature Communications.

“While this phenomenon has been so far studied in very neutron-rich nuclei, its manifestation in nuclei residing on the proton-rich side remains to be explored in detail due to the experimental difficulty of producing medium-heavy-mass N ~ Z nuclei,” the authors wrote. “The two isotopes [reveal] a profound change in their structure and affords deeper insight into the evolution of the nuclear structure at the proton-rich side of the stability line.”

Almost as complicated as the discovery itself are the methods that the scientists used to make it. First, the team bombarded a beryllium target with accelerated Mo-92 ions, and separated the desired fragments out after the collisions. When resulting Mo-86 atoms struck a second target, some were excited into Mo-84, emitting gamma rays in the process. Those gamma rays were then measured by the GRETINA gamma-ray spectrometer and the TRIPLEX (Triple Plunger for Exotic beams) instrument, both of which can record extremely short atomic lifetimes. The resulting data allowed scientists to discern nuclear deformation.

This new “Isospin-Symmetric Island of Inversion” shows that while we’ve made a lot of progress since Rutherford’s experiments in the early 20th century, there are still many nuclear mysteries out there waiting to be solved.

Darren lives in Portland, has a cat, and writes/edits about sci-fi and how our world works. You can find his previous stuff at Gizmodo and Paste if you look hard enough.