This post was originally published on here

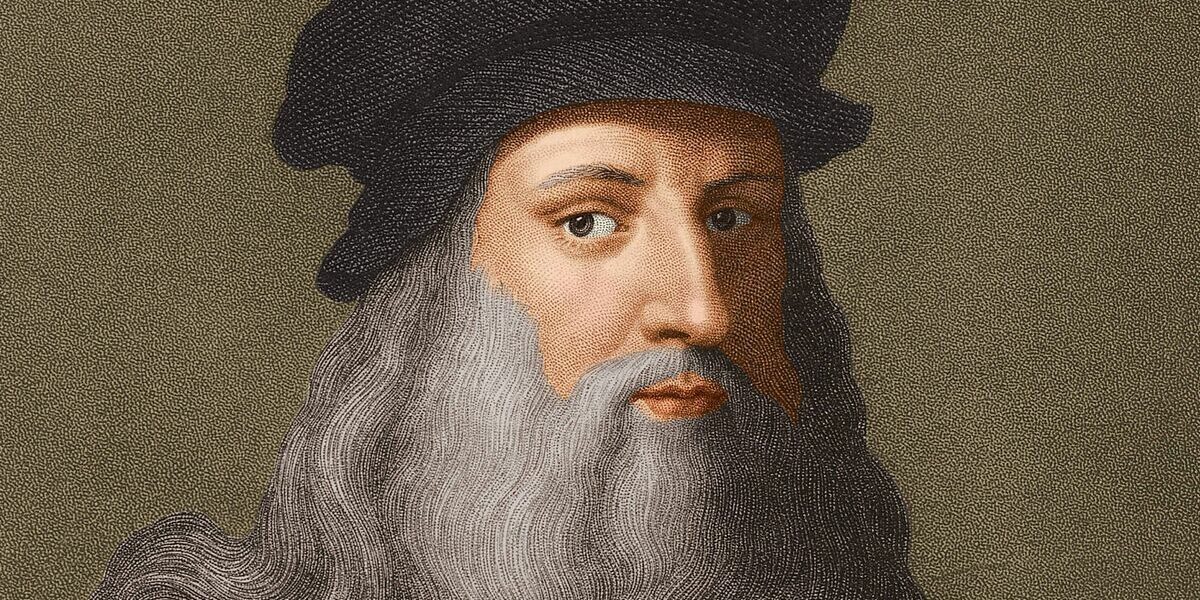

Scientists have managed to extract DNA from one of Leonardo da Vinci’s works, potentially offering a glimpse into the genetic makeup of one of history’s greatest artists and inventors. The DNA was recovered from microscopic traces found on a red chalk drawing titled Holy Child.

The Y-chromosomes scraped from the artwork were compared with DNA from a letter written by one of Leonardo’s cousins. The results suggest a genetic link to people with shared ancestry in Tuscany, where Leonardo was born.

However, it’s challenging to confirm whether this is indeed da Vinci’s DNA, as he has no known descendants and his burial site was disturbed in the early 19th Century.

Despite this, researchers believe the discovery could provide a tantalising hint that some of the genetic material may belong to the master himself.

In their quest for answers, scientists collected tiny flakes of skin, sweat residue, fibres, pollen and dust from the drawing and letters penned by Leonardo’s relatives, which are held in Italian archives.

While most of the genetic material came from microbes, plants and fungi, the team also detected sparse male human DNA.

When compared to large reference databases, the closest matches to these chromosomes traced back to southern Europe, including Italy, as well as North Africa and parts of the Near East, reports the Daily Star.

Given the Tuscan heritage of Leonardo’s family, this pattern aligns with a potential connection to the artist.

As reported by Science Magazine, beyond the human traces, the study could also illuminate the Holy Child’s origins and journey.

Plant species synonymous with the Arno River basin in Tuscany, such as Italian ryegrass and willows utilised in workshops of the era, have been discovered, along with citrus DNA.

However, at present, there is no definitive method to confirm whether any of the human DNA traces originated from Leonardo himself.

Centuries of handling, restoration, and storage mean these artefacts have likely gathered DNA from numerous individuals over time, complicating efforts to isolate the original biological material.

The researchers suggest that future endeavours will need to differentiate between ancient, artefact-associated DNA and modern contamination.