This post was originally published on here

Octopuses are the undisputed kings of camouflage. Whereas engineers have learned to mimic the colors, octopuses also match the texture, disappearing into the background with a level of sophistication that has baffled scientists for decades.

Now a team at Stanford University has come strikingly close to cracking the code.

In a study published in Nature, researchers describe a soft, flexible material that can rapidly change both its color and its surface texture, revealing intricate patterns finer than a human hair. The research links optics and soft materials to produce surfaces that change in ways familiar from living organisms.

“Textures are crucial to the way we experience objects, both in how they look and how they feel,” said Siddharth Doshi, a doctoral student in materials science and engineering at Stanford and the study’s first author. “These animals can physically change their bodies at close to the micron scale, and now we can dynamically control the topography of a material—and the visual properties linked to it—at this same scale.”

Writing Textures with Electrons

The foundation of this new “photonic skin” is a thin film of a common conducting polymer called PEDOT:PSS. You’ve likely already interacted with it—it’s used in displays, solar cells, and bioelectronics. But the polymer has a useful quirk: its structure rearranges and swells when exposed to water or certain solvents.

The Stanford team discovered they could precisely control that reversible deformation using electron beams, the same tools used to etch nanoscale features onto computer chips. By exposing different regions of the polymer film to different doses of electrons, they subtly altered how much water each region could absorb later.

When the film is dry, it lies flat and featureless. Add water, and carefully programmed landscapes rise up.

The patterns appear fast, within seconds, and can be erased just as quickly. The researchers showed that they could switch the same film through hundreds of swelling and shrinking cycles with little degradation.

Using electron-beam patterning, the team recreated a nanoscale topographic replica of Yosemite’s El Capitan. When wet, the iconic granite monolith emerges from an otherwise smooth surface; when dry, it vanishes again. Texture alone, however, is only half of what makes octopus skin so effective.

Turning Texture Into Color

Of course, texture is only half the battle. In living cephalopods, color comes from chromatophores, pigment-filled cells that expand and contract. Meanwhile texture comes from muscle-driven protrusions called papillae. The two systems are controlled independently, giving octopuses their remarkable visual range.

To mirror that separation, the Stanford researchers paired their shape-shifting polymer with thin layers of gold.

When a single gold layer coats the polymer, swelling creates microscopic hills and valleys that scatter light in many directions. The surface shifts from glossy to matte, changing how it reflects its surroundings. This control over how shiny or hazy something appears is difficult to achieve with conventional displays, which rely almost entirely on pixels and brightness.

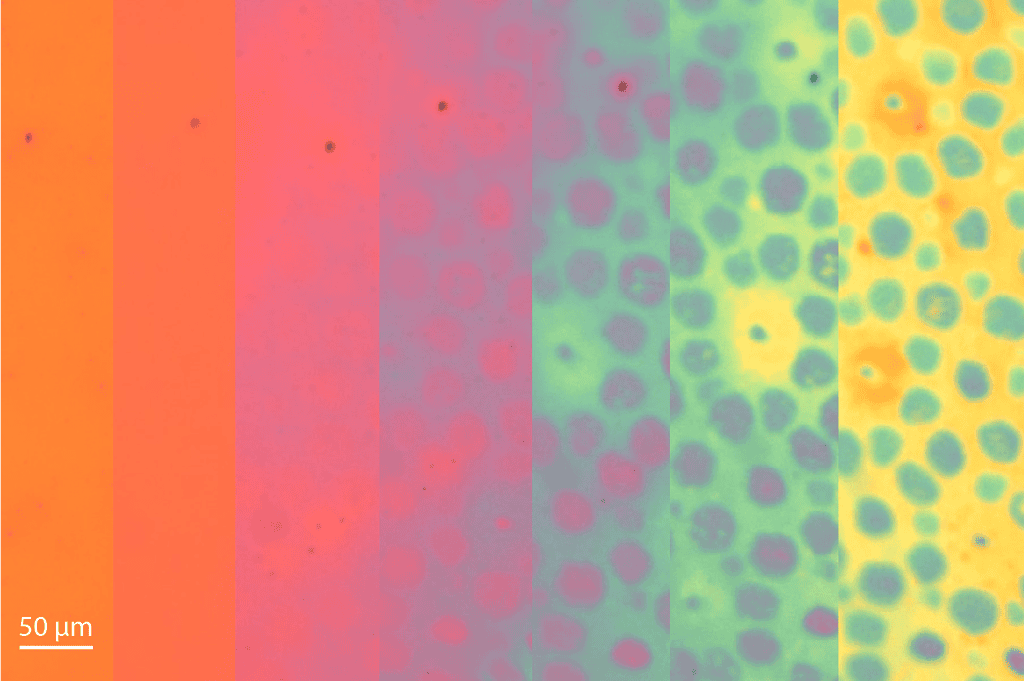

To control color, the team sandwiched the polymer between two gold layers, forming what physicists call an optical cavity. Light entering the cavity bounces between the metal layers, and only certain wavelengths reinforce themselves and escape. As the polymer swells and shrinks, the cavity’s thickness changes, and so does the color it reflects.

The result is structural color, produced not by pigments but by the geometry of the material itself. This is similar to the shifting hues of soap bubbles or butterfly wings.

“By dynamically controlling the thickness and topography of a polymer film, you can realize a very large variety of beautiful colors and textures,” said Mark Brongersma, a Stanford professor and senior author of the study. “The introduction of soft materials that can expand, contract, and alter their shape opens up an entirely new toolbox in the world of optics to manipulate how things look.”

By stacking layers and exposing each side to different liquids, the researchers demonstrated independent control of color and texture in a single device. The material could show color without texture, texture without color, both together, or neither—four distinct visual states.

Beyond Camouflage

The most obvious application is camouflage, for both humans and machines. A surface that can match not just the color of its surroundings but also their texture could fool eyes (and cameras) far more effectively than today’s adaptive materials.

But the implications stretch further.

Texture at microscopic scales influences friction, adhesion, and how cells behave when they touch a surface. Materials that can switch between smooth and rough on demand could help small robots grip walls, guide the growth of living cells in biomedical devices, or regulate how light spreads through optical systems.

There are limits. For now, the system relies on liquids—water and alcohol-like solvents—to trigger its transformations, which complicates integration with electronics. Some researchers argue that electrical control would be more practical in real-world devices.

The Stanford is well aware of this. Prior work has shown that PEDOT:PSS can swell and shrink in response to electrical signals, hinting at future versions that dispense with liquids entirely. Computer-vision systems and neural networks could eventually automate the process, allowing materials to adjust themselves to unfamiliar environments in real time.

“There’s just no other system that can be this soft and swellable, and that you can pattern at the nanoscale,” said Nicholas Melosh, a Stanford professor and senior author. “You can imagine all kinds of different applications.”

Octopuses still do it better. Their skins are alive, responsive, and powered by biology honed over millions of years. But with this work, engineers have taken a decisive step toward materials that change their very shape; and in doing so, how we see them.