This post was originally published on here

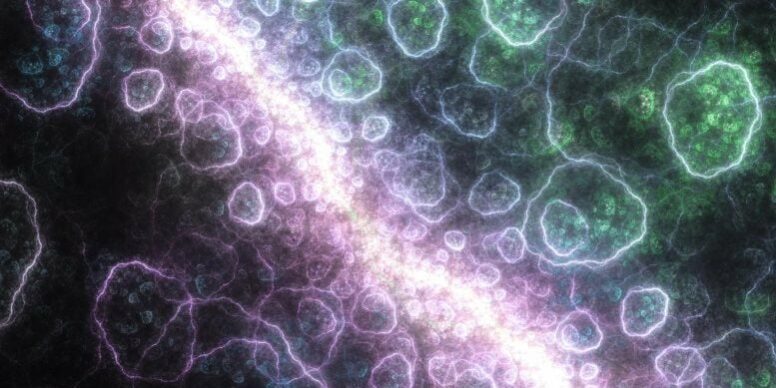

Deep-sea sediment layers show rare microbial wrinkle structures that formed in environments far beyond the reach of sunlight.

Dr. Rowan Martindale, a paleoecologist and geobiologist at the University of Texas at Austin, was hiking through Morocco’s Dadès Valley in the Central High Atlas Mountains when an unusual detail in the rocks made her stop.

She and her team, including Stéphane Bodin of Aarhus University, were moving through the rugged landscape to investigate the ecology of ancient reef systems that once lay beneath the sea.

Reaching those reefs meant crossing repeated stacks of turbidites, sediments left behind by powerful underwater debris flows. Turbidites often preserve ripple marks, but Martindale noticed something else layered on top of the ripples. The surface showed small, irregular corrugations that did not fit what she expected to see.

An Unexpected Pattern in the Rocks

“As we’re walking up these turbidites, I’m looking around, and this beautifully rippled bedding plane caught my eye,” says Martindale. “I said, ‘Stéphane, you need to get back here. These are wrinkle structures!’”

Wrinkle structures are small ridges and shallow pits, ranging from millimeters to centimeters, that can develop on sandy seafloors when algae or microbes grow into mats or clumped layers. These fragile textures are usually erased when animals churn the sediment.

That is why they are uncommon in rocks younger than 540 million years, after animal life rapidly diversified and began disturbing seafloor surfaces more extensively. In modern environments, wrinkle structures are most often associated with shallow tidal zones where photosynthetic algae can grow.

The problem was that the turbidites Martindale was studying formed in water too deep for sunlight to penetrate, at least 180 meters below the surface. That depth rules out the same kind of photosynthetic algae that typically produce wrinkle structures today. Earlier reports of wrinkle structures in ancient turbidite deposits had also been challenged, adding to the skepticism.

On top of that, these rocks were only about 180 million years old, a time when seafloor habitats were widely disrupted by animals, making preservation of such delicate features unlikely. Everything about the setting suggested the textures should not have survived, and Martindale knew she would need to scrutinize the evidence carefully before trusting what she had found.

“Let’s go through every single piece of evidence that we can find to be sure that these are wrinkle structures in turbidites,” says Martindale, because wrinkle structures, usually photosynthetic in origin, “shouldn’t be in this deep-water setting.”

Testing the Evidence

When the team closely examined the geologic evidence and determined that the sediment layers were indeed turbidites, the next step was to make sure the textures they observed were definitely biotic wrinkles. Analysis revealed the layers just below the wrinkles contained elevated levels of carbon—a signature of biotic origin. Furthermore, videos from remotely operated submersibles taken of the seafloor well below the photic zone showed that microbial mats could form from chemosynthetic bacteria—bacteria that get energy from chemical reactions rather than light.

Combining the evidence from the geologic setting, chemistry, and modern analogs satisfied the team that they had documented chemosynthetic wrinkle structures in the rock record. They determined that the turbidites bring nutrients and organic matter with them, reducing oxygen levels and creating conditions ripe for chemosynthetic life.

Then, in the calm periods between turbidite deposition, those bacteria form mats atop the sediment that subsequently wrinkle into the distinctive texture Martindale observed in Morocco. Usually, the next turbidite erodes away the mat, but every once in a while, the mats and their wrinkles are preserved.

Implications for the Search for Early Life

Going forward, Martindale hopes to conduct laboratory experiments to explore how these structures might form within turbidites. She also hopes that these findings spur other researchers to incorporate chemosynthetic mats in a paradigm that previously included only a photosynthetic mat origin for wrinkle structures. Then geologists could look for wrinkle structures in new places that were previously written off as fruitless settings in the search for early life on Earth.

“Wrinkle structures are really important pieces of evidence in the early evolution of life,” says Martindale. By ignoring their possible presence in turbidites, “we might be missing out on a key piece of history of microbial life.”

Reference: “Chemosynthetic microbial communities formed wrinkle structures in ancient turbidites” by Rowan C. Martindale, Sinjini Sinha, Travis N. Stone, Tanner Fonville, Stéphane Bodin, François-Nicolas Krencker, Peter Girguis, Crispin T.S. Little and Lahcen Kabiri, 3 December 2025, Geology.

DOI: 10.1130/G53617.1

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.