This post was originally published on here

Across vast subterranean networks beneath southeastern Europe, entire ecosystems persist without sunlight. In these lightless spaces, some of the fundamental rules governing life at the surface, photosynthesis, competition, even solitude, are often suspended. Here, biology is shaped not by light and plant life but by gas, minerals and chemical energy. Few terrestrial environments are so radically disconnected from solar input, or so biologically compressed.

Near the Greece–Albania border, one such system has become a subject of growing scientific attention. A limestone cave complex laced with geothermal springs, saturated in hydrogen sulfide, and sealed off from the rhythms of the surface has revealed unusual forms of adaptation and survival. Energy here begins with microbes that oxidise sulfur, feeding small insects and invertebrates that form the base of an isolated food chain.

Now, in one section of this chemically distinct cave system, researchers have found a structure that appears to violate long-held expectations of arachnid behaviour. Spanning over 100 square metres, the formation is not a single web but a dense, interconnected network inhabited by tens of thousands of spiders from two separate species. Both are typically solitary, both widespread in urban and forested environments.

The discovery, reported in a peer-reviewed study published in Subterranean Biology, raises questions not only about behaviour in extreme environments but about the thresholds at which familiar species shift away from baseline ecological norms. The structure may represent the largest documented web on record, and the first known instance of colonial cohabitation between Tegenaria domestica and Prinerigone vagans.

Dense Web Architecture Inside Sulfur Cave

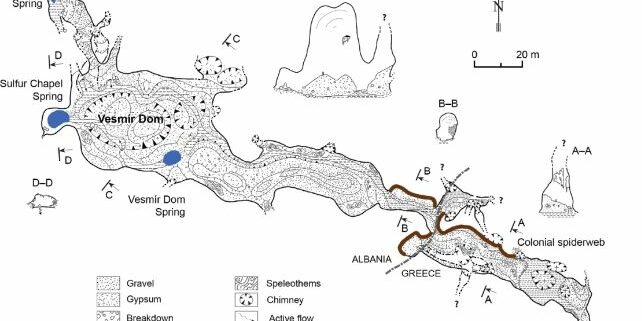

The site, known as Sulfur Cave, lies within a karst system that includes the adjacent Atmos and Turtle caves. According to fieldwork conducted by researchers from the Sapientia Hungarian University of Transylvania, the web structure covers over 1,040 square feet and houses a combined population of more than 111,000 spiders. Population estimates include approximately 69,000 T. domestica and over 42,000 P. vagans.

The web is composed of a dense mesh of funnel-shaped structures, with T. domestica serving as the principal architect and P. vagans occupying existing sections without contributing to construction. Despite the substantial size disparity between the two species, researchers observed no signs of predation, displacement or spatial conflict.

Spatial mapping showed that the two species occupy clearly delineated areas of the network. The arrangement supports what the authors described as facultative coloniality, a non-obligate form of cooperative behaviour triggered under specific environmental conditions.

© Cave On Europe’s Border Hides 111,000 Spiders In The World’s Largest Known Web Structure. Credit: Urák et al., Subterr. Biol., 2025

DNA analysis confirmed the presence of genetically distinct populations. No evidence of recent migration or gene flow was found between cave-dwelling spiders and nearby surface populations, suggesting long-term isolation. The species maintain their core morphological characteristics but exhibit behavioural modifications not previously associated with their genus.

The scale and ecological implications of the discovery were first covered widely by Scientific American, which highlighted the extreme environmental conditions and the unexpected social cooperation between solitary species.

Subterranean Food Web Fuelled by Sulfur

Unlike surface ecosystems that rely on photosynthesis, Sulfur Cave is sustained by chemoautotrophic bacteria. These microorganisms oxidise hydrogen sulfide, forming dense microbial biofilms along the cave walls. Insect larvae and small midges feed directly on the microbial mats, creating a closed-loop food web disconnected from solar input.

Stable isotope analysis (δ¹³C and δ¹⁵N) conducted by the research team traced the spiders’ diet to a single prey species: the midge Tanytarsus albisutus. This insect, in turn, consumes the sulfur-fed biofilms, linking the arachnid predators to the cave’s foundational microbial processes. No secondary food sources were identified during the sampling period.

Microbial diversity within the spiders’ gut contents also differed markedly between populations. T. domestica individuals found near the cave entrance displayed more varied microbiomes than those found deeper inside, suggesting a more homogeneous diet among the cave-adapted population.

A detailed overview of the discovery’s broader ecological context and behavioural significance was published by The Daily Galaxy, which reported that scientists described the web complex as “architecture on a different scale” and noted its central role in an entirely sulfur-based ecosystem.

The study noted that the entire ecosystem shares structural features with deep-sea vent communities, where organisms rely on chemical energy rather than light. However, Sulfur Cave’s significance lies in its accessibility and the presence of surface-derived species adapting to subterranean constraints.

Reproduction, Behaviour and Genetic Divergence

In addition to behavioural adaptation, the study documented changes in reproduction and population structure. T. domestica egg sacs were found in higher concentrations during early summer, with individual sacs containing significantly more eggs than those observed in other seasons. This seasonal pattern may reflect synchronisation with midge abundance, although further research is required to establish direct correlation.

Researchers reported no interspecies mating behaviour. Genetic sequencing confirmed that both T. domestica and P. vagans had diverged measurably from nearby surface populations, with fixed haplotypes observed in multiple individuals. This suggests that the cave colony is not a seasonal or transitory group but a long-established and reproductively isolated population.

Morphological assessments did not reveal any significant physical changes compared to surface-dwelling individuals, indicating that behavioural adaptation has likely outpaced morphological divergence within the isolated environment.