This post was originally published on here

The Coca–Cola recipe is one of the world’s most closely guarded trade secrets – but it may not be secret for much longer.

Zach Armstrong, a scientist who runs the YouTube channel LabCoatz, claims to have cracked the 139–year–old mystery formula.

According to his experiments, the taste that so many of us love turns out to be more than 99 per cent sugar.

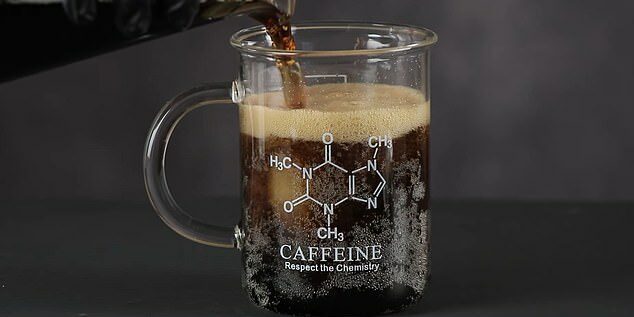

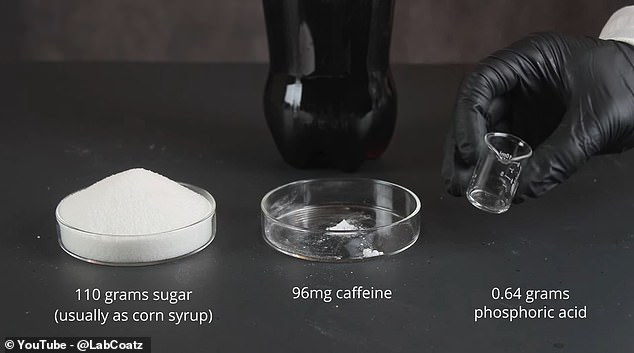

This probably won’t come as a huge surprise – just by reading the label, you can learn that a litre of Coke contains about 110g of sugar, 96 milligrams of caffeine, 0.64 grams of phosphoric acid, and caramel colouring.

However, that doesn’t necessarily mean bottling your own fizzy drinks at home will be easy.

Coca–Cola’s real secret is the composition of the ambiguously named ‘natural flavours’ which give Coke its distinctive taste.

Figuring out what made up that remaining one per cent took Mr Armstrong over a year of scientific analysis, taste tests, and trial and error.

And the resulting formula costs just pennies to make an almost endless supply of Cola.

What makes Coca–Cola so difficult to replicate at home is not just the secrecy with which the formula is guarded, but the legal status of its key ingredient.

One of the main flavourings in Coke is a cocaine–free extract of coca leaves.

This extract is produced by the Stepan Company, which is the only commercial entity in the US with a licence to import coca leaves, and they do not sell to the public.

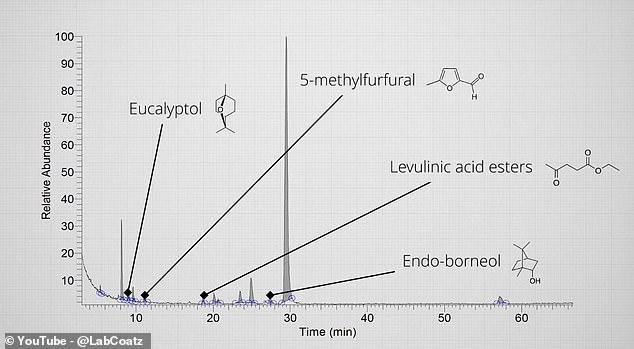

However, that didn’t put off Mr Armstrong, who recruited the help of a chemical test called mass spectrometry.

This process breaks a substance down into an electrically charged gas and separates it into its component molecules, creating a ‘fingerprint’ of all the different components.

Equipped with this fingerprint, Mr Armstrong was able to start building up a chemically exact replica of Coke without any coca leaves at all.

The basic recipe involves mixing a wide variety of essential oils in a very precise ratio.

Mr Armstrong’s recipe included lemon oil, lime oil, tea tree oil, cinnamon oil, nutmeg oil, orange oil, coriander oil, and a natural pine–like flavour called fenchol.

This mixture then needs to be allowed to age for at least 24 hours before being diluted with food–grade alcohol. Amazingly, the mixture is so concentrated that a single batch of essential oils is enough to make 5,000 litres of Coca–Cola.

However, Mr Armstrong wasn’t quite happy with the flavour of his Coke substitute yet.

A study published in 2014 by food scientists from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign found that Coca–Cola also includes fresh and cooling flavour notes that are often overlooked.

Despite matching the chemical fingerprint of Coke almost exactly, the replica formula was still lacking these notes.

The breakthrough was realising that coca leaves are essentially a form of tea, which are naturally rich in chemicals called tannins. Tannins are naturally occurring chemicals with a bitter or astringent flavour found in wine, tea, coffee, chocolate, and nuts.

They produce the puckering or drying mouth feel that you might associate with a very dry red wine or bitter espresso. However, since tannins are non–volatile, they don’t usually show up in mass spectrometry, which explains why they were so easily overlooked.

Luckily, wine tannins are also commercially sold in a water–soluble powder form that could easily be added to the cola recipe.

For the final product, tannins and water are mixed with caramel colourings, vinegar, glycerin to thicken, caffeine, sugar, vanilla extract, and phosphoric acid. A litre of the water–based solution is then flavoured with just 20 millilitres or a highly diluted version of essential oil mix, heated, and mixed with carbonated water.

According to Mr Armstrong and his taste testers, the result is almost indistinguishable from the real thing.

Although the initial cost of the ingredients and necessary equipment is quite high, once diluted, it costs just pennies to make litres of Coke.

And, importantly for anyone who wants to try this at home, all of the ingredients are completely legal and obtainable through online marketplaces.

However, Mr Armstrong does point out that some of the chemicals can be irritating or toxic when undiluted, and suggests using appropriate protective equipment to handle them.

The Daily Mail has contacted Coca–Cola for comment.