This post was originally published on here

OPINION

Taking a recent journal report by Chinese scientists on the discovery and analysis of rare earth minerals near his birthplace in Tibet to task, Tenzin Jigmey* argues that scientific exploration must account for local impact and incorporate local knowledge rather than view resources only through a technical lens, leaving the local inhabitants to bear the long-term consequences—environmental degradation, loss of land, and social disruption—without meaningful compensation or participation.

1. Introduction

Recently, Chinese geologists posted on Sciencedirect.com about “Be–Nb–Ta mineralization in Nyalam granites” and “rare-earth element (REE) enrichment in southern Tibet.” While most scientists accept these as facts, to me, they are more personal. My central argument is that while scientific discoveries bring knowledge, they can also obscure and overshadow the stories, rights, and well-being of the local Tibetan people whose land is affected. This sense of personal connection shapes how I respond to the scientific claims.

I was born near Nyalam, under the very mountains now studied by Chinese scientists. But I, like many Tibetans, was forced to leave long before the geologists arrived. Despite my displacement, I still remember yak bells in the valleys and the scent of juniper smoke at dawn. These memories remain vivid and comforting, even though Nyalam and the Shigatze are no longer my home.

Once, my dad said these colorful granites were precious, showing off Nyalam’s beauty to locals. Reading scientific papers about Nyalam’s mineral wealth provokes a complex response: pride, grief, anger, and longing. My ancestors’ land always felt special, even though I cannot live there. However, local people will not benefit; a Chinese state-owned company will. More than 150,000 Tibetans have been displaced since the 1950s, revealing deeper social and political issues. (Democracy, n.d.) The thought of a mine run by outsiders replacing a once-lively village intensifies both my pride and sadness over its loss.

To understand the significance of these discoveries, it’s important to consider where they take place. Nyalam, a town in southern Tibet under the jurisdiction of Shigatse City, sits at an elevation of about 3,750 meters near the border with Nepal, along the Friendship Highway (China National Highway 318), which connects Tibet to Nepal.

When I read these reports, I do so not just as a Tibetan who loves science, but also as someone from those mountains. The articles detail concentrations, element movement in molten rock, and magma cooling; yet the stories of people living there are left out. This omission is significant, as the personal stories of Nyalam’s valleys and mountains are essential to understanding their true value.

In this article, I will explain which minerals are present in Nyalam and who benefits from their discovery. To provide a clear structure, I will address these key questions:

– Who benefits from the mineral discoveries in Nyalam?

– What are the consequences if a Chinese state-owned company begins exploiting these resources?

I will also discuss why each mineral and element matters to the Chinese economy. By connecting rare-metal science to the reality of displacement, I hope to show that discoveries in Nyalam have far-reaching consequences—scientific, economic, and social—for Tibetans like me. My core argument is that scientific exploration must account for local impact rather than view resources only through a technical lens. This connection between science and personal experience is central to my perspective.

2. Geological Setting of Nyalam

Controlling Nyalam lets China develop and manage trade routes into South Asia, connecting Tibet by road and possibly rail to nearby countries for more economic and political influence. As we move from the geopolitical to the geological, it’s important to note that Nyalam lies within the Himalayan orogenic belt, formed by the collision of India and Asia. The area has evolved granites, pegmatites, and metamorphic rocks. These rocks slowly reveal their rare metals as conditions change. The magmatic bodies here are good at forming rare metals, just as a pot slowly brings out flavors as it boils. Nyalam Tong La is near the southern edge of this region, between the Tibetan Plateau and the inner Himalayan slopes, revealing its mineral layers one by one. The minerals, rich in rare-earth magnetic properties, have significant potential.

2.1 Chemistry of Rare-Earth and Rare-Metal Enrichment in Nyalam

Nyalam lies along the Great Himalayan Belt, a zone created by the collision of the Indian and Eurasian plates. This region contains:

• Leucogranites (light-colored granites)

• Pegmatites with extreme element enrichment

• Late-stage hydrothermal veins

• High-grade metamorphic rocks

These rocks were once 20–30 km deep, heated to 650–750°C, and then slowly became exposed. As rocks heat and melt, rare metals Be, Nb, Ta, Li, and REEs enter the melt. As magma cools, rare elements do not fit into common mineral crystals like quartz or feldspar and become concentrated in the remaining melt. Repeated cycles of melting and crystallizing continue until only a small melt remains. At this last stage, rare element concentration can be over 100 times higher than in magma.

Scientists now understand that Nyalam’s granites contain:

• 100–284 ppm Be (beryllium)

• 24–117 ppm Nb (Niobium)

• 15–102 ppm Ta (Tantalum)

Turning to specific minerals, let’s begin with beryllium (Be), a key component found in Nyalam’s granites. Let’s discuss the elements or Minerals one by one:

Beryllium has very low density (lighter than aluminium), high stiffness (stiffer than steel), a high melting point, and excellent thermal conductivity. Beryllium metal and its alloys are used in satellite structures, missile guidance systems, space telescopes, electronics, and semiconductors for high-frequency microwave devices, X-ray windows, RF transmitters, and semiconductor manufacturing equipment.

Next are niobium (Nb) and tantalum (Ta). Tibet’s mineral wealth plays a crucial role in China’s resource strategy. Estimates suggest total revenue from extracting niobium and tantalum may rival Tibet’s GDP. These elements are strategically important for electronics, medical devices, and steel, making them key areas of interest for China.

3. The Pain of Watching Outsiders Benefit from My Land

What hurts is not science; I value geology. But it hurts every Tibetan who watches their land being turned into a resource by the Chinese state enterprise. My main point throughout this article is that scientific investigation, when carried out by outsiders without inclusion or regard for local voices, risks deepening injustices and erasing Tibetan perspectives. The article mentions there will be no local Tibetan ownership, no local consultation, no benefit to the displaced, and no acknowledgement of Tibetan heritage. Chinese state-owned teams now extract data, samples, and potentially profit, while Tibetan families displaced from the area still lack rights. They gain access to our ancestral land, so local Tibetans lose everything. Instead of ending on this note of despair, I wish to reach out and ask: Can we explore cooperative protocols that genuinely honor the voices of the displaced? Can scientists engage with local communities in meaningful ways that respect and incorporate our stories and perspectives into their research? By inviting such partnerships, we can seed solutions that transform our pain into shared understanding and cooperative action.

The paper on Nyalam’s Be–Nb–Ta mineralization may seem normal to many, but to me it stands for a land I cannot return to and a story excluding Tibetan voices. I know scientists cannot solve politics, but they can choose ethical approaches. This prompts a key question: Whose knowledge does your mapping serve? By asking, I seek to challenge professionals and open a dialogue about their moral responsibilities.

I wish geological papers would acknowledge Tibetan communities, recognize cultural landscapes, encourage fair benefit-sharing, avoid focusing solely on resource potential without human and environmental context, offer explanations in Tibetan for locals, and note the risks of state exploitation without consent. Science is credible when it includes people’s connection to place.

For a way forward, picture community ownership and shared responsibility. Imagine royalties that benefit locals directly and that wealth supports sustainable development and cultural preservation. Another model is participatory mapping, which integrates local insights into science so that all voices are heard. Moving toward such models could empower locals and foster justice and sustainable growth.

4. Environmental and social impact of mineral extraction in Nyalam.

4.1 Land disturbance and geomorphological instability

Be–Nb–Ta mineralization in Nyalam is found mostly in leucogranites and pegmatites on steep Himalayan slopes. Mining uses open-pit methods, removing overburden and host rock. Given Nyalam’s steep slopes, tectonics, and seismic activity, mining will likely increase landslides and sediment in rivers and may even cause plate shifting.

4.2 Water contamination and hydrological impacts

Nb–Ta–Be-bearing granites commonly contain associated rare-earth minerals, such as monazite and xenotime, which may also carry traces of Thorium (Th) and Uranium (U). (Rare-earth element – Minerals, Ores, Uses, n.d.) Mining the Nyalam ore processing could release radioactive particulates, heavy metals, and acidic drainage from sulfide-bearing accessory minerals. The Nyalam area lies within the headwaters of transboundary river systems flowing into Nepal and South Asia. Contamination could therefore affect downstream drinking water, impact agriculture and livestock, and create international environmental concerns. Under the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention, the potential for water contamination should be viewed not only as an ecological issue but also as a significant international legal concern. This convention underlines the importance of cooperation between nations sharing watercourses and highlights the necessity for equitable and reasonable utilization of transboundary water resources.

4.3 Chemical processing risks

Extraction of Be, Nb, and Ta requires aggressive chemical processing, often involving hydrofluoric acid, sulfuric acid, and alkali fusion methods. Like other mining stations in Tibet, the entire mountain in the area will be impacted by acidification. Improper waste handling may result in soil acidification, fluoride contamination, and long-term tailings toxicity. Beryllium compounds are also toxic if inhaled, posing risks to workers and nearby populations. (Frequently Asked Questions: Beryllium and Beryllium Compounds, 2024) These chemicals used in open-pit mining could cause permanent vegetation loss, habitat fragmentation, and disruption of wildlife migration routes.

5. Impacts on Local Tibetan Communities

For Tibetans living around Nyalam, the land is not simply a resource; it is the foundation of livelihood, identity, and spiritual life. Traditional ways of living have long depended on seasonal pastoral grazing, small farming, and the care of sacred landscapes. Mountains, springs, and monasteries are not separate from daily life; they are integral to cultural and spiritual practice. If mining were to begin, access to pasturelands would likely be restricted, migration routes disrupted, and culturally significant sites damaged or rendered inaccessible. These changes threaten not only the economy but the cultural fabric of Tibetan life. For pastoralists, rituals such as seasonal yak-herding journeys and annual prayer offerings at mountain passes would be at risk of disappearing. The seasonal routes, used for generations, play a crucial role in the rhythm of life and in maintaining the spiritual connection to the land. These losses would not be measured only in economic terms but in the erosion of relationships between people, land, and belief systems that have endured for generations.

Experience from other mining regions in Tibet suggests that local communities rarely share the economic benefits of extraction. Employment is often temporary or brought in from outside, decisions are made far from the affected villages, and profits flow to state or corporate entities. Meanwhile, Tibetans are left to bear the long-term consequences—environmental degradation, loss of land, and social disruption—without meaningful compensation or participation. (Tibet Rights Collective – The Hidden Cost of Mining: How Operations Like the Jiama Mine are Damaging Tibet, 2025)

Health risks further compound these concerns. Exposure to beryllium dust, contamination of water by heavy metals, and the psychological stress of displacement pose serious threats, especially in remote Himalayan areas where access to healthcare is limited. (Assessment of the health risks associated with heavy metal contamination in the groundwaters of the Leh district, Ladakh, 2024, pp. 27645-27656) For communities already living at the edge of environmental and political vulnerability, such risks are not abstract—they directly affect survival and well-being.

Finally, mining in Nyalam would not remain a local issue. The region’s high-altitude river systems flow beyond Tibet into Nepal and South Asia, meaning environmental damage could travel far downstream, affecting ecosystems and communities that had no voice in the original decision. In this way, extraction in Nyalam connects local loss to regional consequences. For those born near Nyalam and now living in exile, these developments are deeply personal. The land continues to give—through rare minerals formed over millions of years—yet the people who belong to it are excluded from both access and benefit. This imbalance highlights the urgent need to consider not only what the land contains, but who pays the price when it is taken.

5. Conclusion: Science, Responsibility, and the Meaning of Place

This paper has argued that the significance of Nyalam’s mineralization cannot be fully understood without acknowledging its human context. Environmental risks such as geomorphological instability, water contamination, chemical processing hazards, and long-term ecological degradation are inseparable from social consequences, including loss of traditional livelihoods, cultural erosion, and health vulnerabilities. These costs are borne disproportionately by local and displaced Tibetans, while economic benefits are concentrated elsewhere.

The ethical responsibility of geoscientists does not lie in resolving political disputes, but it does include recognizing whose knowledge is amplified and whose is silenced. Scientific practice gains legitimacy when it acknowledges local histories, engages affected communities, and situates the potential of resources within environmental and social realities. Incorporating participatory mapping, transparent impact assessments, and fair benefit-sharing mechanisms would not weaken scientific rigor; rather, it would strengthen the credibility and relevance of geological research in contested regions.

For those of us born near Nyalam, these discoveries are not abstract. They speak to a land that continues to give, even as its people remain excluded. By integrating scientific insight with ethical awareness, geology can move beyond extraction-focused narratives and toward a more responsible engagement with place. Only then can science truly honor both the deep time recorded in rocks and the human lives shaped by the land above them.

***

References

Democracy, T. C. (n.d.). Resettlement is Displacement: The Plight of Tibetans in Tibet. https://tchrd.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Click-here-to-download-TCHRDs-special-report-on-the-right-of-the-internally-displaced-in-Tibet.pdf

(May 4, 2023). Net Profits of Tibet Mining in 2022 Increased by about 467.45% amid Falling Chrome Ore Supply and Rising Sales and Prices. Shanghai Metals Market. (n.d.). Rare-earth element – Minerals, Ores, Uses. Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/rare-earth-element/Minerals-and-ores

(2024). Frequently Asked Questions: Beryllium and Beryllium Compounds. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). https://www.osha.gov/beryllium/rulemaking/faq

(March 26, 2025). Tibet Rights Collective – The Hidden Cost of Mining: How Operations Like the Jiama Mine are Damaging Tibet. Tibet Rights Collective. https://www.tibetrightscollective.in/news/the-hidden-cost-of-mining-how-operations-like-the-jiama-mine-are-damaging-tibet

(2024). Assessment of the health risks associated with heavy metal contamination in the groundwaters of the Leh district, Ladakh. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 31(22), pp. 27645-27656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-024-25556-0

—

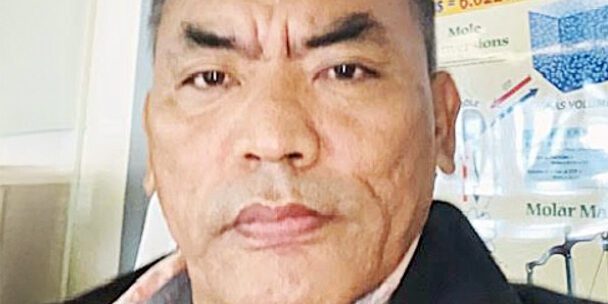

* Tenzin Jigmey is presently a high school chemistry teacher and an adjunct lecturer at Union County College in New Jersey. With years of experience in both education and laboratory work, he brings a unique perspective, having journeyed from the Tibetan exile school system to the American education system. His reflections draw on his personal experiences as a student, teacher, and community member dedicated to education and growth.