This post was originally published on here

New research could help conserve the world’s rarest marsupial.

New findings from Edith Cowan University (ECU) could strengthen efforts to safeguard one of the planet’s rarest marsupials.

The Gilbert’s potoroo, a critically endangered marsupial found only in Western Australia, now survives in the wild in numbers estimated at fewer than 150 individuals.

To support the species’ survival, researchers from Edith Cowan University (ECU) have partnered with the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA) to study what the animals eat, aiming to use this knowledge to help stabilize and protect remaining populations.

“We are looking to recover the species through translocations, which is moving organisms from one location to another to create an insurance population in case anything was to happen in their existing populations,” School of Science PhD student Rebecca Quah explains.

“In doing that, one of the challenges was trying to determine what they are eating and where those resources can be found. Mycophagus – or fungi-eating mammal diets are quite hard to study because a lot of fungi remain undescribed.”

Non-invasive diet analysis

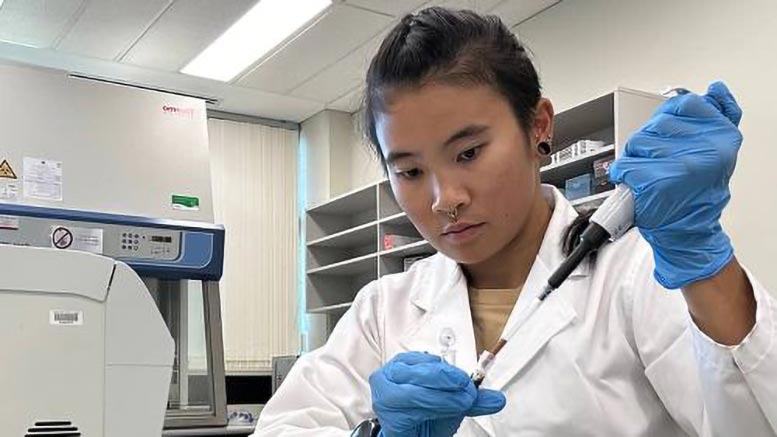

Ms. Quah explained that the team used environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding to analyze scat (faeces) samples, an approach that is becoming more widely used to study the diets of wild animals.

“Traditionally, researchers would go through undigested material in scats to study animal diets, but trying to identify fungal spores remained a challenge,” Ms. Quah said.

“This research used a molecular technique, known as eDNA metabarcoding to decipher what animals are eating. It’s a non-invasive way of studying diet and all you need are fresh scats from the environment.”

The study examined whether the diets of more common fungi-eating mammals overlapped with that of the Gilbert’s potoroo, based on the idea that these species historically lived alongside one another.

“We examined quokka, quenda, and bush rat scats and found that there was some overlap in the diet of the four mammals, and that habitat use between the quokka and potoroo were also really similar,” Ms. Quah said.

“Based on our results, we recommend focusing on areas where all three species persist together as an indicator of suitable food, or habitat, for future potoroo translocation sites.”

A rediscovered species

Once thought to be extinct, several methods to boost the numbers of Gilbert’s potoroos have been attempted since they were rediscovered in 1994.

“Soon after their rediscovery, breeding them in captivity was tried, but that didn’t work out, particularly because of how picky they are with their food resources,” she said.

“This is why wild-to-wild translocations are so important. In 2015, a bushfire destroyed 90 percent of core potoroo habitat in Two Peoples Bay, which is home to the only natural population of Gilbert’s potoroo. Fortunately, insurance populations had been established on Bald Island and in a fenced enclosure at Waychinicup National Park by DBCA.

DBCA Research Associate Dr Tony Friend said with the critically endangered population scattered across four sites, two of which are islands off the Western Australian coast, researchers are hoping to find another mainland site for a translocation.

“The search for new translocation sites is an important next step in the recovery of Gilbert’s potoroo from near extinction. This publication shows that examining the fungal diet of mammals that occur with the potoroo can help in deciding where to establish new populations,” Dr Friend said.

Ecosystem engineers

The broader topic of Ms. Quah’s PhD is looking at the conservation and translocations of fungi-eating mammals.

“Fungi-eating mammals are ecosystem engineers – they dig for fungi which helps in soil turnover, and they act as vectors for fungal spore dispersal.

“Fungi have several ecological functions, including having mutually beneficial relationships with plants, so mycophagous mammals are really important in maintaining healthy ecosystems.

“Unfortunately, many of Australia’s mammals are threatened because of predation from introduced cats and foxes. That is why it is vital that we do everything we can to help protect our native wildlife, and translocations are one important way to accomplish that goal.”

Reference: “Gilbert’s Potoroo and the fun-guys: Co-existing mycophagous mammals as indicators of potentially available fungal food resources” by Rebecca J. Quah, James Anthony Friend, Aaron J. Brace, Saul J. Cowen, Robert A. Davis, Harriet R. Mills and Anna J. M. Hopkins, 01 November 2025, Biodiversity and Conservation.

DOI: 10.1007/s10531-025-03193-9

This work was supported by funding from the Royal Society of Western Australia’s John Glover Research Grant, awarded to author Rebecca J. Quah (grant number G1007039/24914).

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.