This post was originally published on here

Scientists have identified a hidden geological weakness beneath Greenland’s ice sheet that could accelerate its collapse, and complicate US ambitions in the Arctic.

A new study discovered a hidden layer of sediment, composed of soft dirt and sand, which has driven more of the Danish territory’s glaciers to melt, break apart, and fall into the ocean.

The finding suggested the Greenland ice sheet is far less stable than if it were anchored directly to hard bedrock. Instead, the sediment reduces friction, particularly as meltwater seeps downward, allowing massive ice sheets to move more easily.

The revelations could significantly impact the Trump Administration’s ambitions for Greenland, which the US has looked to acquire from Denmark not only for its strategic location in the Arctic, but also for its wealth of natural resources under the ice.

Mining those resources, including oil, gold, graphite, copper, iron, and other rare earth elements, could be extremely hampered by the presence of sediment layers, which slow down drilling and create dangerous conditions as glaciers collapse.

University of California, San Diego researcher Yan Yang revealed that the widespread sediment layer is up to 650 feet deep in many spots under Greenland’s ice sheet.

While the new study suggested that this secret layer of sediment is likely speeding up the rise of sea levels around the world, other scientists have warned that the immediate impact on Greenland could make the area difficult to utilize long-term.

Recent investigations have shown that safe drilling requires a stable, frozen bedrock base, while offshore oil rigs would face heightened risks and soaring costs from a growing number of icebergs calving into nearby waters.

On Monday, Trump again demanded Greenland be handed over to the US because Denmark couldn’t protect it from Russia and China, according to the Norwegian press.

Although Greenland is a territory of Denmark, a 1941 agreement already authorized the US expansion of its existing military facilities on the island. In previous decades, America operated dozens of bases there.

The Trump Administration has said full control of the island is needed to prevent major adversaries such as Russia and China from using Greenland as a crossing point in an invasion of North America.

Despite being approximately 5,000 miles away from Greenland, China claimed it was a ‘near-Arctic state’ in January 2018 to justify its interests in the region, including the exploration of Greenland’s natural resources and use of its shipping lanes.

The study, published in Geology, found soft sediment layers under much of the Greenland Ice Sheet, but noted they are not spread out evenly, with the sands ranging from very thin layers of roughly 15 feet to some spots where the slippery dirt is 1,000 feet deep.

The thickest sediments were mostly in areas where the bottom of the ice is warmer and wetter, while thinner layers or no sediments appeared in colder, frozen zones – explaining why they’re not breaking up as fast.

‘If more meltwater reaches the bed, these sediments may further reduce strength, speed up ice flow, and increase ice loss to the ocean,’ Yang warned in a statement.

‘This means some regions of Greenland may be more vulnerable to climate change than current models assume.’

When it comes to extracting Greenland’s resources, a 2022 study in The Cryosphere found that the current drills limit where mining can be done, needing a solid surface like frozen rock to keep the drilling site stable.

In a 2024 study in Annals of Glaciology, researchers found similar conditions that have derailed drilling in Antarctica could cause major problems for future campaigns for precious metals in Greenland, which Trump has made a priority to acquire.

‘Drilling through subglacial sediment and clay overburden can stall drilling and substantially impact the time required to reach bedrock,’ the international reach team wrote.

Specifically, hundreds of feet worth of dirt and sand can repeatedly clog drill bits, leading to slower progress, equipment damage, and the need to stop operations in unstable areas frequently.

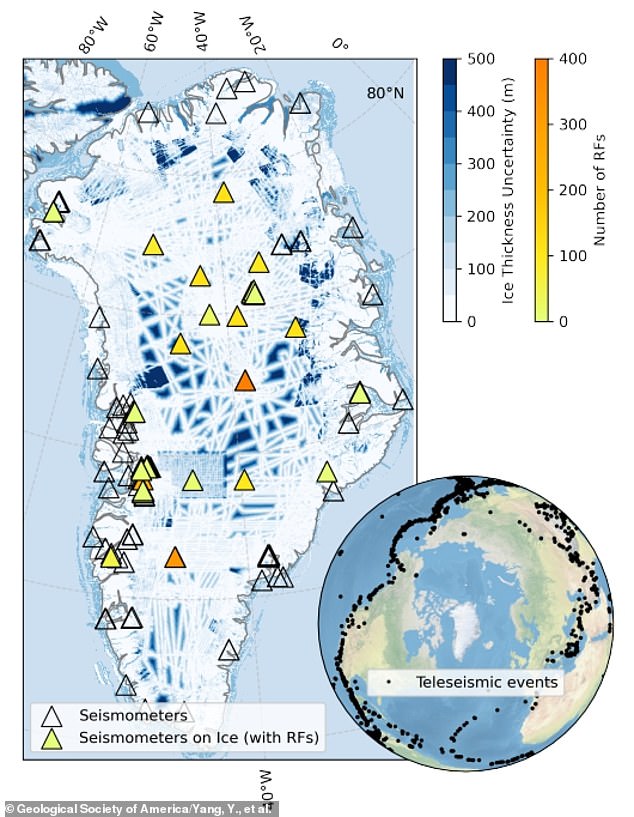

Yang’s research team gathered earthquake vibration data from 373 monitoring stations spread across Greenland over the last two decades.

They analyzed how these vibrations traveled through the ice and ground below, looking for delays in the signals that suggested a soft layer between the ice and hard rock.

By comparing the real data to computer models of just ice on rock, they uncovered where and how thick the hidden sediment layer must be to explain the delays in seismic readings.