This post was originally published on here

The Stevens Institute of Technology in the US recently said some of its scientists plus a group at Yale University will be building “the world’s first experiment explicitly designed to detect individual gravitons”. The announcement has already drawn sceptical attention from the physics community — but also $1.3 million from the W.M. Keck Foundation.

The plan is to use an ultra-sensitive antenna of sorts to listen for the impact of the particles of gravity. The device of choice is a cylindrical resonator made of superfluid helium. The researchers chose this material because they can control it precisely at a macroscopic scale. To detect something as faint as a graviton, the detector must be completely free of noise, so the team plans to cool the cylinder down to its quantum ground state, where it will have no thermal vibrations. It will effectively be waiting in near total silence.

When a strong gravitational wave, e.g. from a pair of black holes merging together, passes through the detector, the theory posits that it could transfer exactly one quantum of energy, i.e. a single graviton, into the cylinder. And when it does, the energy will be converted into a mechanical vibration within the cylinder. Lasers monitoring the cylinder will watch out for this vibration, revealing when a graviton has been absorbed.

“This current project is for three years and we aim to have an operational system within this timeframe,” Stevens Institute assistant professor and one of the co-leaders of the new effort Igor Pikovski told The Hindu. “It is unlikely it will be able to detect single gravitons then, but serve as a blueprint for the next iteration.”

A bridge between camps

The graviton is the hypothetical particle of gravity. Scientists don’t know if it’s real but they’ve some reasons to believe it could exist. In modern physics, forces are transmitted by particles. For instance, when two magnets repel each other, they’re actually exchanging streams of (virtual) photons. Physicists believe gravity could work the same way: if the sun pulls on the earth, it could be doing so by exchanging gravitons.

Another way to understand a graviton is to compare it to light. Light is an electromagnetic wave but at the smallest level it’s made of particles called photons. Gravity acts like a wave — they’re called gravitational waves — but at the smallest level, physicists believe, it could be made of particles called gravitons.

If gravitons exist, they’d open the door to a theory of everything. Currently, physics theories are split into two camps: general relativity, which explains the macroscopic universe like stars and gravity using the bending of spacetime; and quantum mechanics, which explains small things like atoms using the properties of particles. The problem is that the maths of these two theories refuse to work together. If physicists find the graviton, it will prove that gravity is also a quantum force like the others — a bridge between the camps.

But detecting gravitons, if they exist, is painful. While physicists have detected gravitational waves, they’ve never detected a graviton. This is like detecting tsunamis but not being sure if water molecules are real.

An aerial view of the LIGO detector site near Livingston, U.S.

| Photo Credit:

LIGO Laboratory/Reuters

Impossible detector

The pain comes from the fact that gravity is such a weak force. Gravity is one of nature’s four fundamental forces; the others are electromagnetism and the strong and weak nuclear forces. And gravity is 1 billion billion billion billion times weaker than the electromagnetic force, the next strongest.

This is why a simple fridge magnet can overcome the gravitational pull of the entire earth to pick up a paperclip. Because the force is so weak, the coupling constant — a number with which physicists measure how strongly a particle interacts with matter — is vanishingly small for gravitons. So while a photon interacts readily with atoms, allowing us to ‘see’, a graviton would pass through matter as if it weren’t there.

For a detector to ‘see’ a particle, the particle must interact with it. The probability of this happening is defined by its cross-section. But the cross-section of a graviton is so small that a graviton with a typical amount of thermal energy could pass through a shield of lead spanning billions of lightyears without being absorbed.

In a 2006 paper, physicists Tony Rothman and Stephen Boughn calculated what it would take to build a detector capable of registering a single graviton. Their findings suggested the task may be physically impossible. They figured experimenters would need a detector with the mass of Jupiter (2 billion billion billion kg), composed of 100% efficient sensor material, placed in close orbit around a neutron star, a source of high-energy gravitons. And even with this extreme setup, they estimated the detector would register one graviton event every decade.

To distinguish that single graviton from the background noise of neutrinos — the universe’s second-most abundant particles and thus vastly more common — the experimenters also will need to shield the detector. But the amount of shielding required would be so massive that the detector would collapse into a black hole under its own gravity. It’s a catch-22 in effect: any detector massive enough to catch a graviton would be too massive to exist.

Finally, the gravitons scientists have access to, from gravitational waves, have absurdly low energy: going by the LIGO instruments data, each graviton would have about 10-13 eV. Even if a single graviton did deposit its energy wholesale, the resulting increase is far, far below ordinary thermal noise and below many irreducible quantum noise sources in measurement.

(This is why gravitational-wave detectors can measure a classical wave, which is a coherent superposition corresponding to an enormous number of gravitons acting together, rather than individual gravitons.)

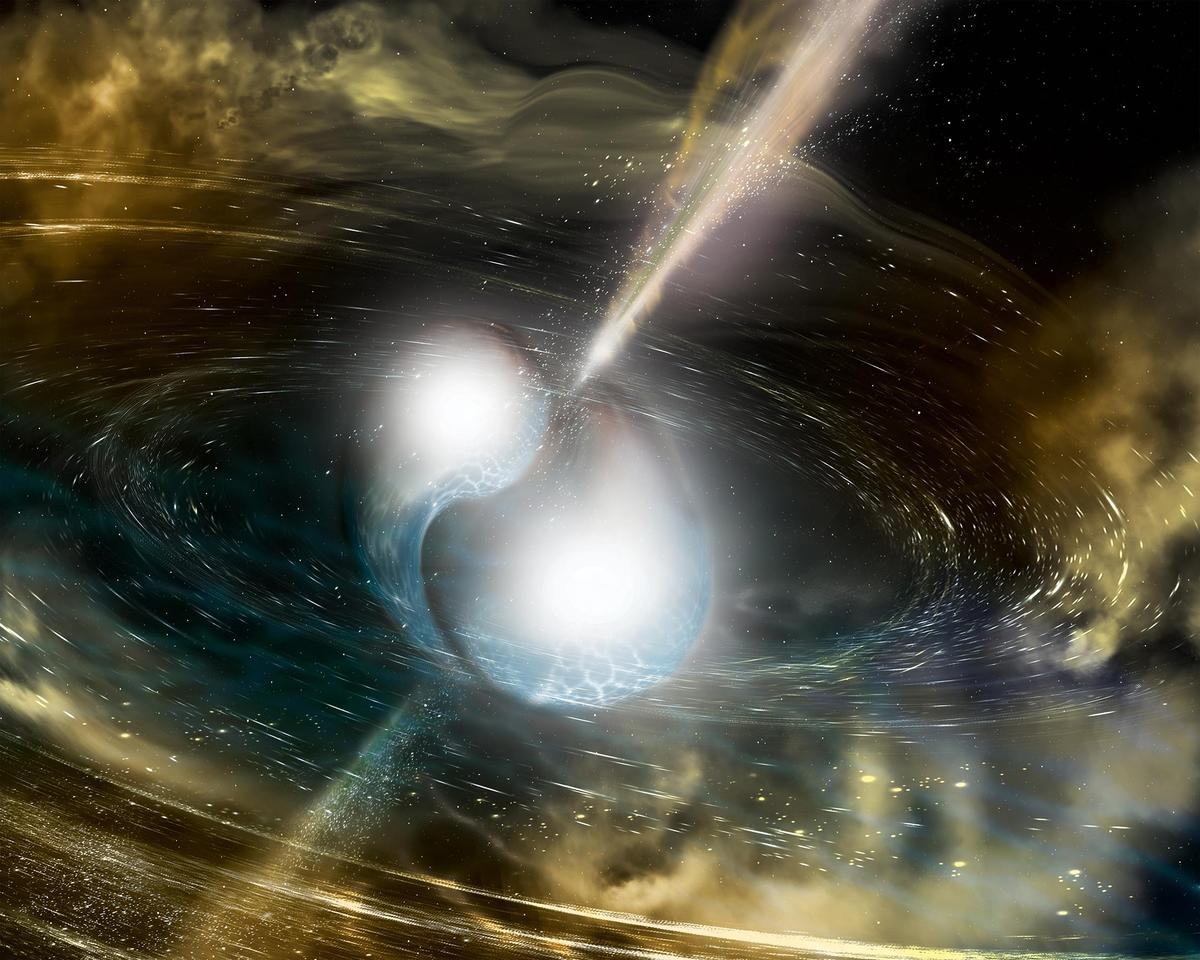

In this artist’s illustration of two merging neutron stars, the narrow beams represent a gamma-ray burst while the rippling spacetime grid indicates the gravitational waves from the merger.

| Photo Credit:

AFP

Breaking a wine glass

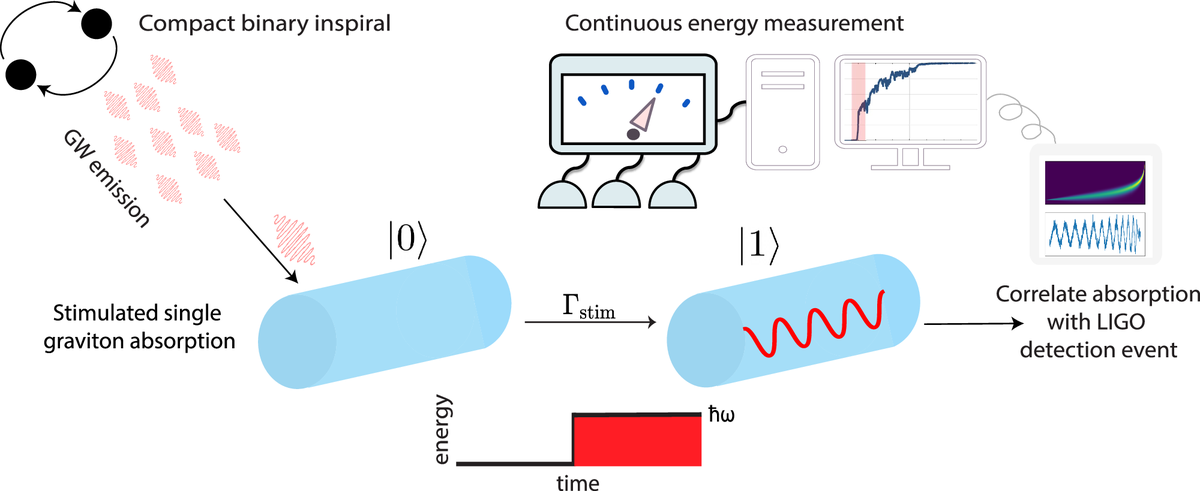

The Stevens-Yale idea is based on two studies published in 2022 and 2024, combining a theoretical prediction with advanced sensors. First, the scientists propose a gravito-phononic effect, similar to the photoelectric effect used in solar panels: that the cylinder cooled to nearly absolute zero will be able to absorb a single graviton from a gravitational wave.

This effect is expected to evade the difficulties posed by the Rothman-Boughn calculations. Rothman-Boughn assumed scientists would catch a graviton the way a wall stops a bullet. But because gravity is so weak, you need an impossibly thick wall. Instead the Stevens-Yale team is building a wine glass. An opera singer can shatter the glass not by hitting it with a rock but by singing a specific note that matches the glass’s natural vibration. Similarly, according to the team, if the helium cylinder is in a quantum state, the graviton won’t have to hit a single atom but will interact with the entire fluid at once.

The resulting absorption is expected to create a single unit of vibration, called a phonon. The second study, in 2024, described a quantum sensor capable of detecting and counting these individual phonons in a massive object.

A schematic illustration depicting the proposed gravito-photonic setup to detect gravitons.

| Photo Credit:

Nat. Comm. vol. 15, article no. 7229 (2024)

‘Won’t teach us anything’

Technologies based on quantum physics have already come a long way since the birth of the theory a century ago. The mid-20th century had semiconductors and transistors and the subsequent revolution in information and communication technologies. Today, scientists around the world are pushing borders by actively manipulating individual quantum states, paving the way for quantum computers, satellite-based data encryption, and ultra-sensitive detectors.

But even if the technologies exist, the physics underlying the new idea has already met with at least one rebuttal. Berkeley National Lab theoretical physicist Daniel Carney wrote on X that “this experiment will not teach us anything whatsoever about gravitons. The signal can be explained purely through classical gravity.”

The basic issue appeared to be two claims in the Stevens Institute press release: (i) that a device could register an event consistent with the helium having absorbed one graviton and (ii) that seeing such events would show that gravity is quantummy. But in a 2023 paper, before the new idea came to light, Dr. Carney and two other physicists had argued that (i) can be true in principle but that wouldn’t mean (ii) is also true.

“I’ve never argued that you can’t detect a graviton, assuming they exist,” Dr. Carney wrote in a subsequent X post. “I’ve only ever been saying that doing so would not teach us anything since you have to assume their existence in the first place to draw that conclusion.”

Ringing the bell

Imagine a bell that can only do two things: stay silent or sound one ding. It can’t sound half a ding or any other sounds. Now say the bell sometimes dings when a gust of wind hits it. Because of the way the bell is built, each gust either fails to ding it or dings it once. As a result, even if there’s a wind blowing continuously, you get multiple single dings or no dings, but you never get a single, continuous diiiiiiiiiing.

The press release is effectively saying that if a gravitational wave makes the helium device sound a ding, it would mean a graviton hit it. But Carney et al. have contended that a single ding only would reveal that the device is either single ding or no ding; it won’t reveal whether the thing that dinged it came in discrete units (gravitons) or was a smooth wave (classical gravity).

“The objection by Carney is a well-known old observation, dating back even to the photoelectric effect: it is possible to describe mere detection by a semi-classical model, which is what we also discuss in our paper,” Dr. Pikovski said.

“Semi-classical” refers to the gravitational waves being classical and continuous whereas the detector detecting them being quantum mechanical and discrete.

To prove each single ding is really a graviton rather than a gravitational wave, the device would have to be capable of more than sounding single dings. For example it would have to have a pattern that only a graviton could produce, or at least a pattern that a smooth wave could never produce on a single-ding device.

First, detect

But Dr. Pikovski said their main goal is to detect the particles rather than unambiguously test “all possible semi-classical alternatives”. “The latter is not the goal of a detector but requires further advancements,” he added. “The historic comparison is the 1905 photoelectric effect insight on the existence of the photon … versus the 1974 first demonstration of anti-bunching, which ruled out semi-classical alternatives. That would be a more firm test of the quantum nature, but not detection.”

So then how will the scientists know if they’ve detected a graviton if it’s also possible to explain that signal perfectly with a semi-classical model?

“In short: energy conservation,” Dr. Pikovski explained. “If the detector ‘clicks’ it absorbed something from the gravitational wave. By energy conservation, this is the definition of a graviton. But one can now also study experimentally some of its properties”.

“But to reiterate again, it cannot exclude all possible semi-classical explanations. In particular, one that doesn’t conserve energy would be indistinguishable in this experiment,” Dr. Pikovski continued. “Just like for photons, one then has more experiments to design and do in the (far) future to really rule everything else out. So it is never ‘bullet proof’, just a degree of empirical evidence that steadily grows. Which is always true in all of physics.

“Overall I think it’s quite possible to have a successful graviton detection within a decade,” he added. “But of course you never know, and there might be surprises.”

Published – January 20, 2026 05:30 am IST

Email

SEE ALL

Remove