This post was originally published on here

On February 3, 1966, the Soviet Union’s Luna 9 became the first human-made object to touchdown on the lunar surface and beam back a photo of the Moon. Since then, the whereabouts of the spacecraft have remained a mystery, but a team of astronomers believe they’re getting close to finding the remains of the long-lost lunar probe.

A team led by Lewis Pinault from the University College London designed a machine learning algorithm to scour through hundreds of images of the Moon’s surface that have been captured by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO). The You-Only-Look-Once—Extraterrestrial Artifact (YOLO-ETA) program scanned the dusty lunar surface in search of Luna 9, and the team has narrowed it down to multiple possible locations. Any of these spots could hold the discarded Luna 9, and the researchers now need a second closer look to find it.

The findings are detailed in a new study published in npj Space Exploration.

Touchdown

The U.S. may have been the first country to land astronauts on the Moon in 1969, but the Soviet Union successfully touched down on the lunar surface three years prior with its Luna 9 spacecraft.

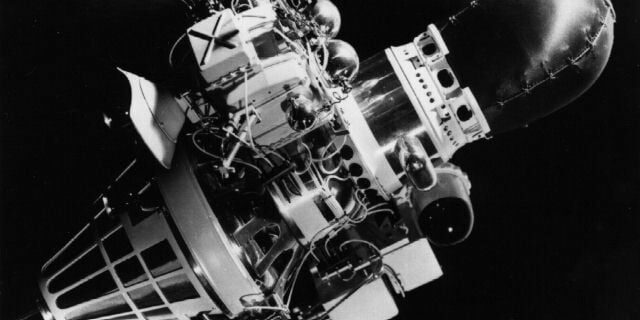

The Luna 9 spacecraft featured an airbag to help it land on the Moon. Credit: NASA

The Soviet probe carried out the first successful landing on a celestial body, touching down on the Moon’s Oceanus Procellarum region. Unlike modern lunar landers built today, Luna 9 deployed a spherical landing capsule with inflatable shock absorbers and fired a breaking engine. The probe bounced around on the lunar surface a few times before coming to a halt using four petal-shaped panels.

Luna 9 sent back the first images taken from the lunar surface and remained operational for three days before its batteries ran out. Since its chaotic landing, however, the spacecraft’s final location on the Moon has remained a mystery.

Enter YOLO

In 2009, NASA’s LRO began returning images of the Moon’s surface. Scientists had hoped that the orbiter would help shed light on the location of Luna 9. Due to outdated calculations and the probe ending up possibly miles away from its intended landing site, the vintage lunar lander has not been found yet.

Using modern techniques, the team behind the new study developed an algorithm able to identify surface features left behind on the Moon by spacecraft that may have been previously difficult to discern. The team tested YOLO-ETA on other landing sites on the Moon, including the site of the Soviet Union’s Luna 16 probe, and found that the program displayed high levels of accuracy.

It then came time for its big mission: scanning the roughly 3 by 3 mile area (5 by 5 kilometers) on the Moon’s surface that the Soviets had initially estimated for Luna 9’s landing site. The researchers narrowed it down to a few possible locations where Luna 9 may have been for the past 60 years, each displaying some levels of artificial soil disturbances.

These areas are worth a closer look, according to the researchers, and they may be able to pinpoint exactly where Luna 9 is rather soon. India’s Chandrayaan-2 is set to launch on its mission to the Moon in March 2026, and the spacecraft will fly over the same regions of the lunar surface identified by YOLO-ETA. Perhaps then, Chandrayaan-2 will finally be able to resolve the mystery of Luna 9’s final resting place.