Arkansas scientists find rice compound may help slow aging

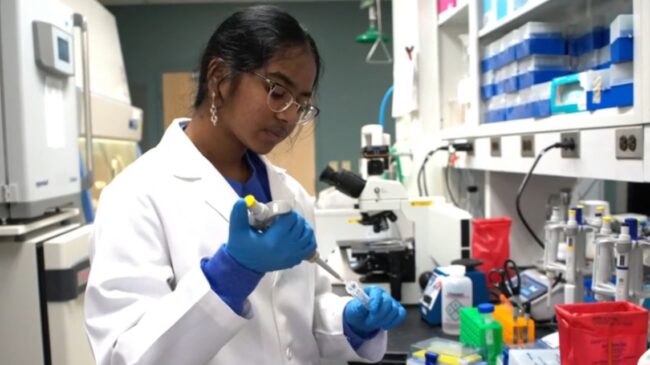

Scientists in Arkansas have determined … on aging.”

Along with scientists at the University of Arkansas … Medical Sciences, Devarajan and UAPB scientists studied rice bran, which … significantly reduced.”

In addition, the scientists found that gamma oryzanol may …